Far away from home but close to the known

October 26, 2018

Flashing lights, flocks of ill-tempered travelers, the symphony of yelling intermixed with cars honking—I was instantly shrouded in the familiar temperament of the city as I stepped outside the arrival hall. Within a matter of minutes, thanks to being a seasoned veteran of John. F. Kennedy airport, I managed to find my Uber. I climbed into the back seat and was ready to collapse in exhaustion.

My driver, a young man in his late twenties named Aurel, started exchanging small talk with me. You see, there are generally two types of Uber drivers—the one that initiates as little interaction as humanly possible and the other who puts in the effort to survey your whole family history; Aurel seemed to be in the latter category.

He found out that I was flying in from Portland, Maine; I learned that he doubled as a delivery driver. We shared a couple light-hearted jokes about how terrible the traffic was (an hour and 15 minutes worth of terrible, to be exact). It was smooth sailing until the inevitable happened.

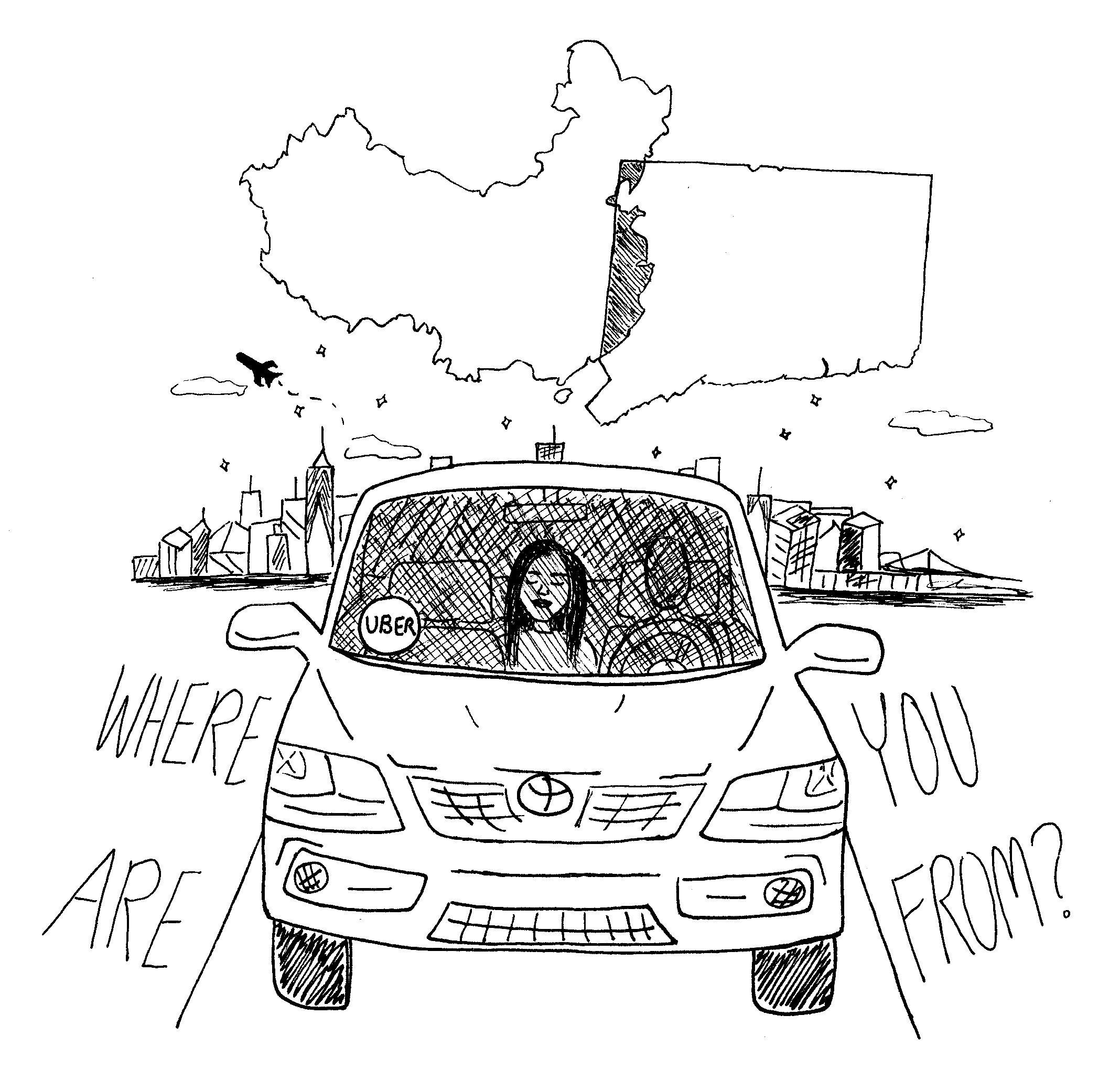

“So, where are you from?” he asked, his dark eyes assessing me from the rear-view mirror.

A lot went through my head in the split between seconds. I have been in this situation too many times to not know what to expect: the standard “Oh, your accent was so good, I had no idea,” followed by “My girlfriend/brother/cousin/neighbour went to China this many years ago,” topped by the ever so pleasant “Do you think you want to stay in the US after graduation?” Time after time, I have unwillingly given strangers my story of how I ended up in this country at age 16. The discomfort of sharing a personal experience is further complicated by an irrational refusal to confirm what was already assumed of me, based on the color of my skin.

Well, not here, not tonight. “Connecticut—I’m from Connecticut,” I replied.

The neon lights of the airport seemed farther and farther away, slowly fading into small and fuzzy splashes of color, illegible against the dark cityscape. My mind was at a loss while Aurel went on about the city’s finest rooftop bars on 7th Avenue. It wasn’t just that I had avoided a direct response to the question, but rather I am apparently conditioned to lie about who I am. Resorting to lying was alarmingly easy and comfortable.

There was some level of truth to that story: Connecticut has a special place in my heart. Three years of boarding school, daily trips to the local pizzeria, hours spent in front of artworks at my favorite museums and the name “Farmington” inscribed into the inside of my ring. It was in Connecticut that I realized my love for art history, found a passion for writing and met some of my closest friends. I consider those three years to be intellectually formative—I’ve read more Joan Didion than I’ll ever her Chinese counterpart. Yet despite all of those things, I do not belong there.

Now replaying the scenario in my head, I am less so troubled by a case of moral integrity, but instead realize that perhaps I’ve lost grip on “what” I truly am.

My closest friends have all heard me complain about life in China to varying extent. My Western education means that I am constantly disheartened by the censorship, the pollution, the legal system, the sexism, the homophobia … and I’ve grown increasingly detached from my life back home. Half-jokingly, I have tried to convince my parents, who speak only a few words of English, to drop their lives and move with me.

Yet inevitably, there are times I feel like an imposter of American culture. I worry about finding acceptance. The more time I spend here, the more I am torn over my inability to truly “fit in.” Despite having a small circle of genuinely amazing friends, I can’t help growing self-conscious of the differences in our upbringings, origins and fundamental experiences.

Other times, I wake my mother in her sleep with hysterical tears. When it strikes, homesickness is a force of nature—unpredictable, illogical, uncontainable. I miss the homecooking of my grandmother. I am overwhelmed with guilt of not spending time with my little brother. Despite all its faults, I selfishly yearn for the ease and comfort of being in China, surrounded by people who look, talk and feel like me.

In Aurel’s Uber, it seemed that I had not simply traveled from Portland to New York. Instead I was caught somewhere in between the place that I was traveling from—a small, prestigious, predominantly white New England institution emblematic of my Connecticut past—and the destination I was running to—my best friend from home with whom I can drink bubble tea, eat Sichuan food and rant about visa struggles. I felt stuck at the edges of two worlds.

The car slowly pulled over; Aurel unloaded my suitcase, shook my hand and wished me a pleasant stay in New York. I dialed my friend’s number as I watched him drive away. He will never come close to knowing what went down in my mind within the span of an airport ride.

So I leaped into the streets of the city, sheltered by my anonymity in the big melting pot that is Manhattan, parting ways with my troubles for as long as I could—that is, until my next ride.

Sabrina Lin is a member of the Class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: