Food for worms: 2 a.m. and contemplating mortality

November 9, 2018

Would you choose to be immortal?

I think it’s fair to generalize that everyone has pondered immortality at some point in their lives. Maybe you watched “Twilight” for the first time and wondered what it would be like to stay a teenager forever. Maybe it was 2 a.m. in a friend’s basement where, due to a lack of both sleep and sobriety, you began to retreat from the room and into your own head. Whatever the reason, we are all obsessed with time—or rather—our lack of time on earth. We see quotes like “Life is short,” “Live in the moment” or even the middle school-era favorite, “YOLO” plastered across t-shirts, hung over toilets and stylized on iPhone backgrounds.

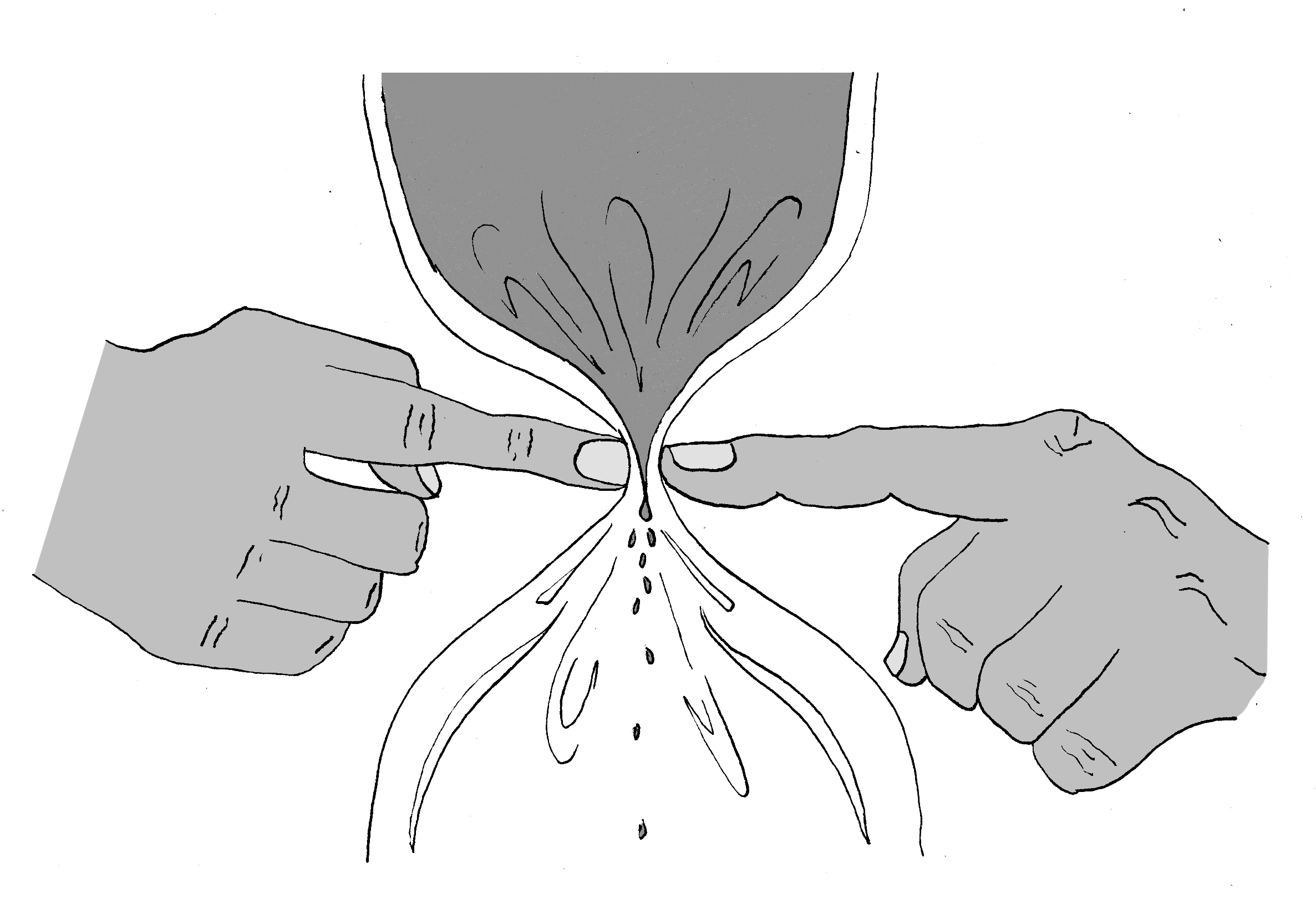

The first time I remember fully processing my own mortality was after watching “Dead Poets Society,” a film about John Keating, an eccentric English teacher who sought to inspire his students to “Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys.” During Keating’s first class, he motivates his students with the uplifting words “…we are food for worms, lads. Believe it or not, each and every one of us in this room is one day going to stop breathing, turn cold and die.”

Those words are so blunt, so violent. Although we all know that death is coming, we often like to sugarcoat its inevitability, because it reminds us just how small we are in the universe.

To what degree does our lack of time motivate us to lead a more meaningful life? I constantly feel an itch to do something impulsive; guilt scratches at my chest when I choose to spend a night in. I wonder if I should be going out of my comfort zone or undergoing a new experience. However, no one has predetermined this elusive “meaning of life.”

Growing up, I sought to discover the career that would be both my greatest passion and allow me to benefit society. I am still scared of wasting my time. If my late-night conversations about immortality have taught me anything, it is that I know some part of us doesn’t want to be forgotten.

But then the question arises: would immortality necessarily guarantee that you would be remembered? Life is anything but predictable. Maybe the opportunity to pause our great ticking clock poses such an unimaginable luxury that you’d accept the choice in a heartbeat. Or, maybe, your own decision would depend on specific conditions. Could you choose the age at which you became “stuck” forever? Would you be immune to illnesses, or would you simply be guaranteed survival, whatever level of pain you may experience? Would you be a victim to the plagues of aging?

Generally, life expectancy rates have steadily climbed over the course of human history. When people lived to only 30 years old, it seems unlikely that they felt a stronger desire to make the most of every day than we do—the idea of living an extra 30 or even 70 years was completely inconceivable. If we believed that we could live substantially longer, I’m unsure that our view of time’s preciousness would change; an end would still be inevitable. If every human became technically immortal, and all causes unrelated to the consequences of aging could kill us, wouldn’t we still view time as precious?

If you were alone in immortality, you may experience indefinite heartbreak as those you loved and cared for passed away. However, wouldn’t indefinite heartbreak be balanced by indefinite love? You would be able to have infinitely wonderful friendships and relationships; throughout your existence, you may also be able to refine the qualities and characteristics you appreciate most in a person.

I have re-watched “Dead Poets Society” since the first time I lay awake late into the night, wholly struck by the ending. Now, I understand that Keating did not want his students simply to live cautiously, constantly aware of the threat of an end. He wanted his students to do whatever made them feel completely alive for as long as they could.

I have learned that you do not need your name on a plaque to be remembered. Personally, I don’t think I would choose to be immortal. My greatest sense of joy comes from the people around me, and I am not sure if I could live as the lone survivor. Maybe I could undergo a fundamental “Groundhog Day”-type transformation and become a phenomenal pianist, make ice sculptures of all my friends’ faces and maybe even learn to like opera. I’ll accept being food for worms. For even when this happens, at least the worms will finish the day satisfied—and isn’t that some type of post-mortem impact?

Kayla Snyder is a member of the class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: