A shiver down the spine

February 23, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Sara Caplan

Sara CaplanEight months ago I checked into Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, changed into a hospital gown and mustard-colored socks and plummeted into the depths of general anesthesia to the sound of Paul Simon’s first solo album.

When I woke up nine hours later in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), the first thing I noticed was that I could move my feet. Great news: not paralyzed. I felt fantastic.

“Not paralyzed!” I remember babbling happily to my mom.

The next thing I did was post before and after X-rays on my “finsta.” I captioned it “not paralyzed!”

Clever.

I called four or five of my friends.

“My knees are swollen!” I told them gleefully.

I was riding high on intravenous methadone, a drug commonly used to help wean heroin addicts into sobriety.

They replaced my methadone with oxycodone the next day, and the reality of my situation started to filter in. I could move my feet, that was true, and my arms, but not much else. With the help of two nurses, a surgeon and a walker, I got out of bed and hobbled laps around the ICU.

Nothing worked the way that it had before. I couldn’t move my head or neck. Each foot fall sent shock waves through my newly reinforced spine that registered as pain even through the cloud of heavy opioids.

The next five days were a blur of doctors, nurses and new pain meds. I watched two whole seasons of “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” and threw up twice each day. I stopped trying to eat because the vomiting sent spasms of pain up and down my back. When I left the hospital six days after the surgery, I hadn’t eaten in a week and my body was so bloated that clothes I had worn to the hospital literally did not fit on my body.

At home, I sat in a chair in my living room for 21 hours each day. The other three I would spend in my bed before waking up each morning at 5 a.m., gasping in pain. Constantly by my side I kept a bowl of medications: one anti-nausea, two laxatives and three different types of painkillers. One of the pain pills triggered my gag reflex, so I took it ground up in a shot of hospital-issued cranberry juice.

Six months later, I’m still hit with waves of pavlovian nausea every time I smell cranberry juice or hear the first notes of the theme song of “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend.”

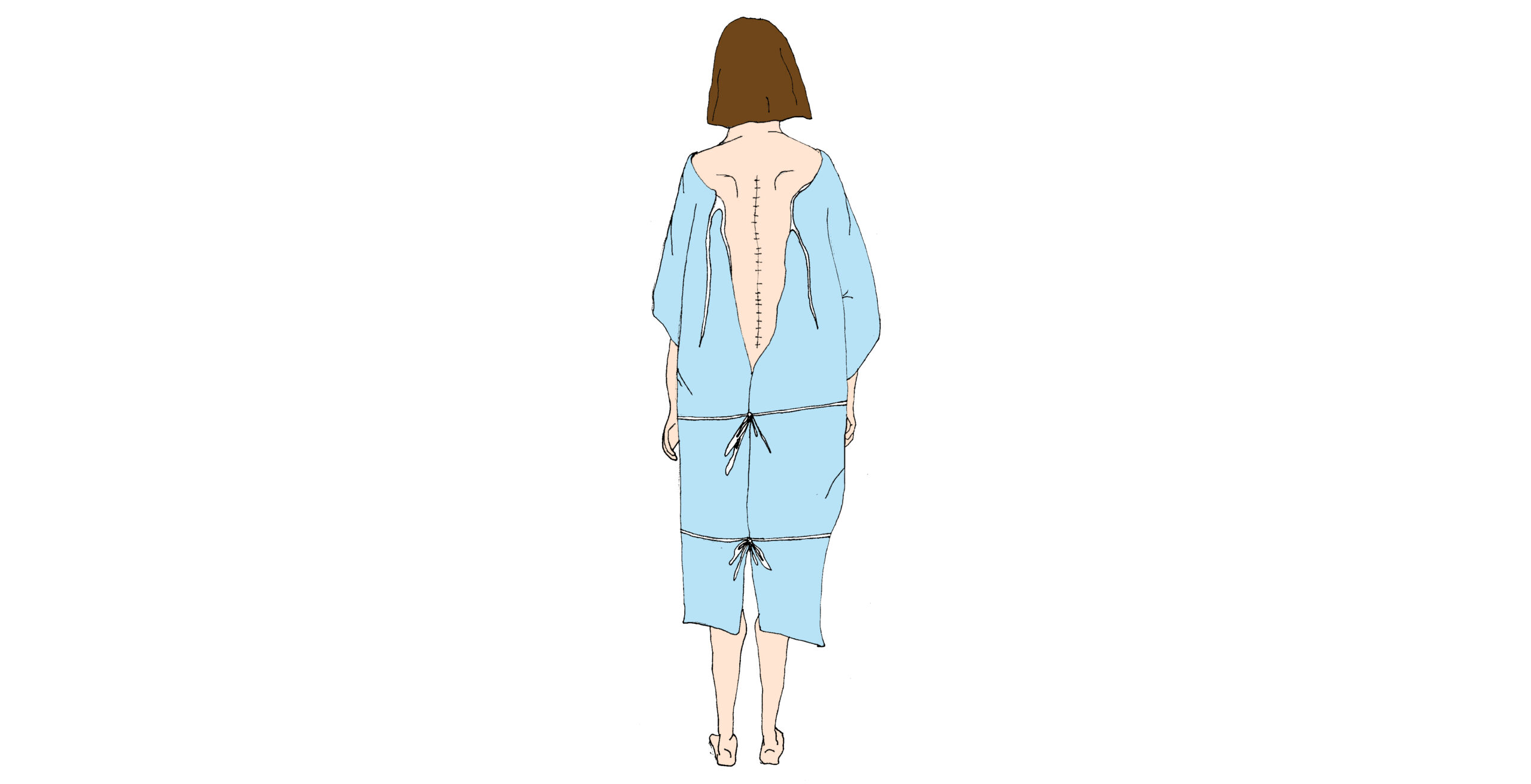

Other than that, I’m mostly fine. There’s a metal rod that runs along my spine from the base of my neck to the top of my waist, secured to the vertebrae with half-inch screws. The spine itself is also fused together using bits of bone from an organ donor. It doesn’t move the way other spines do. It doesn’t expand and contract, doesn’t bend, doesn’t arch. It won’t do any of these things ever again.

I have a scar. I can’t do yoga, touch my toes or play contact sports. Sometimes I get random, shooting pain, but mostly it just aches.

What hasn’t faded in the eight months since the operation is the sense that my body is, in some nebulous way, no longer mine. To be very literal and somewhat reductive, it isn’t: no matter how I try I can’t seem to forget those pieces of foreign bone wedged between my defective vertebrae—a cadaver’s bones among my own—or the metallic dowel to which I can credit my (newly flawless) posture. I want to be poetic about it, to see my augmented backbone it as “cool” or “empowering” or at very least symbolic of some type of courage or resilience gained through adversity—but I don’t.

My feelings of alienation from my physical form run deeper than such platitudes, and I find them exploiting a discomfort and frustration with the human body, with my human body, that is intimately and intensely familiar from years of adolescent insecurity and shame. In an unexpected way, the relationship that I have built with my scar mimics an understanding of my appearance, my body in general. I deeply, deeply want to wear it with pride—an indelible mark of my selfhood and identity—but I can’t seem to surmount a nagging distrust, discomfort, disgust.

I would like this to be a story of recovery and healing in which a surgery and a scar help me understand flaws as beauty and scars as symbols of selfhood, but it isn’t—yet, anyway.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: