Lessons from working through a pandemic

May 1, 2020

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

About a decade ago, in February 2020, I wrote the first installment of this column. Titled “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Technology,” I argued that society should ready itself for an inevitable replacement of work in its traditional sense with automation sometime in the indefinite future. Little did I know that my thesis would be put to the test on a global scale a mere month later. While there are notable differences between the lockdown and a post-work society–i.e. the omnipresent anxiety that has accompanied the plague–the mobilization of social resources to “flatten the curve” has fundamentally disrupted society in a way that has accelerated the transformation of work and consumption.

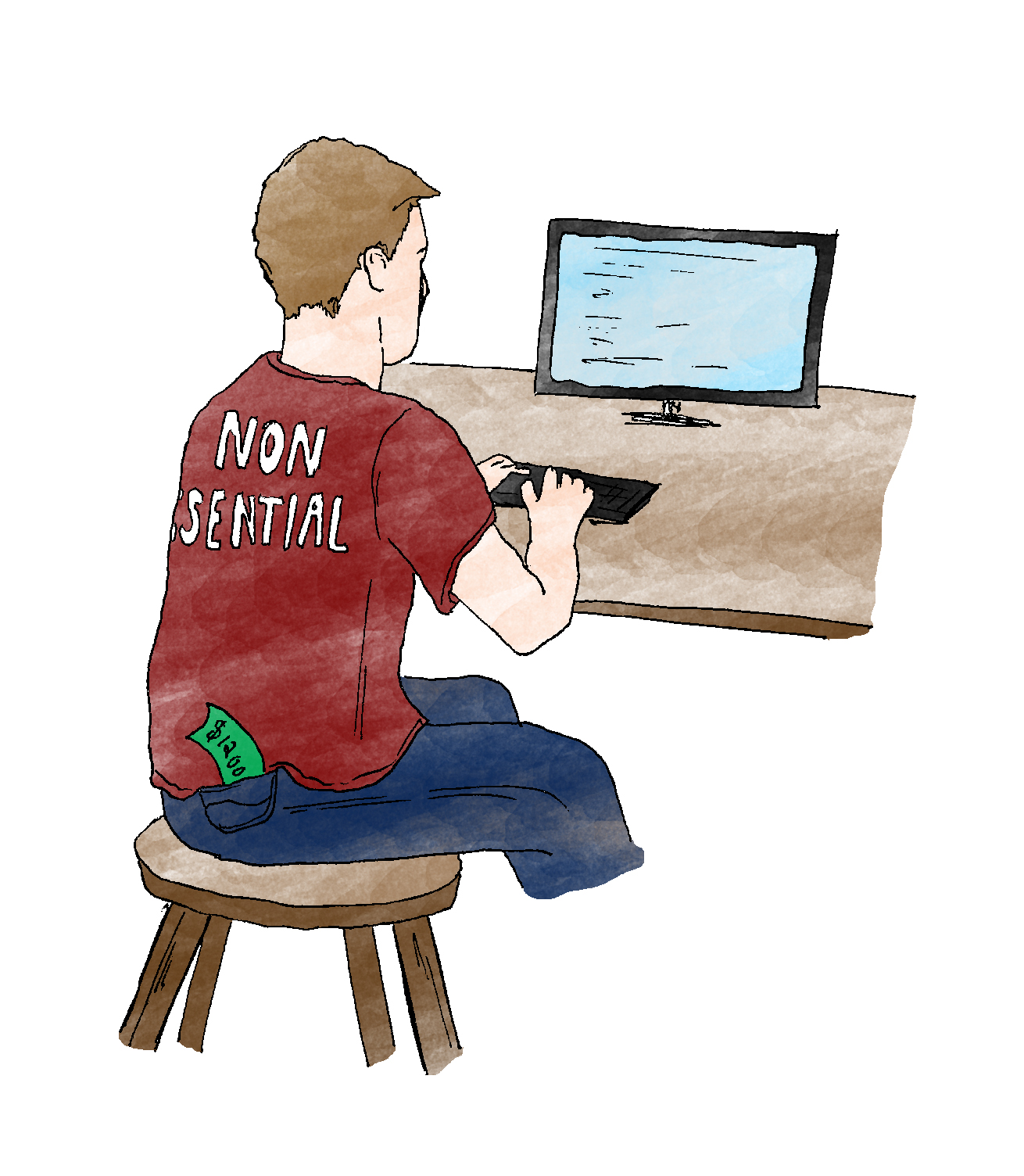

The most palpable irony that has arisen from the crisis has been the sudden distinction between “essential” and “non-essential” labor. A few months ago, the question of which vocations are necessary for the survival of an affluent society and which are the symptoms of affluence seemed ambiguous. Most activities seemed to have a kernel of necessity embedded within a layer of excess. However, as the pandemic crescendoed, we began to realize the fragility of this excess. Whole industries ground to a halt simply because people started to consume only what they really needed and wanted. As the long process of “reopening” begins, we may find ourselves wondering why in the first place we ever allowed the logic of capital to prioritize meaningless toil over meaningful leisure.

In that vein, we also discovered through the emotional toll of quarantine that people with nothing to do are not necessarily more idle than industrious. In fact, the opposite is most likely true. The incentives of work, constructed under the theory that individuals must be cajoled, threatened or forced to contribute to the maintenance of society, have now been revealed to be unwarranted. I know many people rendered jobless by this pandemic, and not a single one relishes the opportunity to do nothing at all.

When I was writing my first article, the 2020 presidential election still seemed like it would be the most important event of the year, and Andrew Yang was hovering in the single digits of most early state primary polls. While I had expected that Yang would be the beginning of a gradually escalating movement for universal basic income, I didn’t realize how much of a Cassandra he really was. More Americans than ever are acquainting themselves with the welfare system and a free $1200 has already appeared in most individuals’ bank accounts. The Federal Reserve has decided to make the money printers go “brrr” without concern for inflation or the deficit. All of these developments suggest we are reaching a new stage in our relationship with money, one which finally severs the fictional connection between labor and individual income.

On the other hand, I should note that working from home has lessened my expectations for a post-work society brought about by technological obsolescence. Specifically, it has proved physically and mentally taxing at best to shrink the workplace to fit a screen, despite remote connection being easier than ever. Zoom meetings, as it turns out, are woefully inadequate substitutes for in-person interaction. It has been proved that human interaction is irreplaceable, indivisible and deeply difficult to commodify. Instead of capitulating to technology, the experience of living through a pandemic could cause us to reconsider our priorities in life. The restlessness of American life could come to an end, ushered by the death of business travel, mass events and conspicuous consumption. The local and personal could replace the global and anonymous. While I still believe that work will be phased out in the near future, it’s possible that social change—not technology—will be the harbinger of its demise.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: