Who’s the boss?

April 17, 2020

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Kyra Tan

Kyra TanOnce upon a time, company towns dotted the American landscape. From Pullman, Illinois (railroad cars) to Logan, West Virginia (coal mining), these towns proliferated in the latter part of the 19th century as a way to concentrate laborers and tie them to their place of work. The calculus of living in one of these towns was pretty simple. You (and everyone you know) crank out a specific product. The company sells it, revenue flows in and they give you a cut in the form of wages. It’s about as close as you can get to a theoretical model of worker exploitation. Owing to this fact, company towns were often the site of intense labor militancy around the turn of the century.

Frightened by the threat of radical projects such as unionization and the eight-hour workday, the robber barons of the 19th century turned into the benevolent patrons of the 20th. Compromise between labor and capital ushered in a new era of capitalist paternalism. Health insurance became tied to one’s job, and progressive taxation exploded. Company towns had achieved an air of modest affluence. Management structured both the economic and social life of American communities. It was the heyday of Carnegie libraries, the Chamber of Commerce, Main Street and the single-income family. Most reasonably-sized towns and suburbs across America tried to reap the benefits of corporate citizenship. Society—having understood the corporation as necessarily possessing social responsibilities—became a company town.

Before long, however, paternalism began to chafe. The conformism of the company town ranged from the relatively benign (the rise of vapid consumerism) to the reprehensible (bigotry). Meanwhile, the global economic boom precipitated by the Second World War began to cool off. The company town, with its vigorous compromise between capital and labor, simply could not accommodate the economic growth that the public came to expect. Hippies and neoliberals, therefore, emerged from the same primordial soup of disillusionment with the company town. They had a cosmic conception of human society. They embraced the chaos of individual action and had faith that true order could only be attained through the natural, uninhibited unleashing of human passion. Americans became obsessed with discovering their true selves, unlocking their potential and intuiting personal success. It was far out, man.

The cosmic idea permeated the corporate world. Wall Street realized that in order to achieve self-actualization, it could no longer tolerate the company town. The historic compromise between labor and capital fettered the sacrosanct ecology of the free market. Corporations had one overriding purpose, equivalent to the natural drive in living things to eat and reproduce: fiduciary duty. The imperative to maximize shareholder value subverted the paternalistic promise of corporate citizenship. Management had to march in lockstep with ownership, uniting the orthodoxy of capital with control over workers.

The convolution of ownership and management has led to confusion over the reality of worker exploitation in modern society. Yes, managers play an important role in the workplace, and their labor deserves remuneration. However, the manager is not entitled to collect profit—that is, garnish the wages of their employees—for the mere fact of coordinating the workplace. In fact, many worker-run cooperatives take on managers simply because management is valuable in and of itself. The managers are, in that case, no more than fellow workers. The role of ownership, on the other hand, is totally unnecessary apart from providing the initial investment. The beneficial aspects of the company town were the product of management having a degree of interest in developing worker well-being apart from profit.

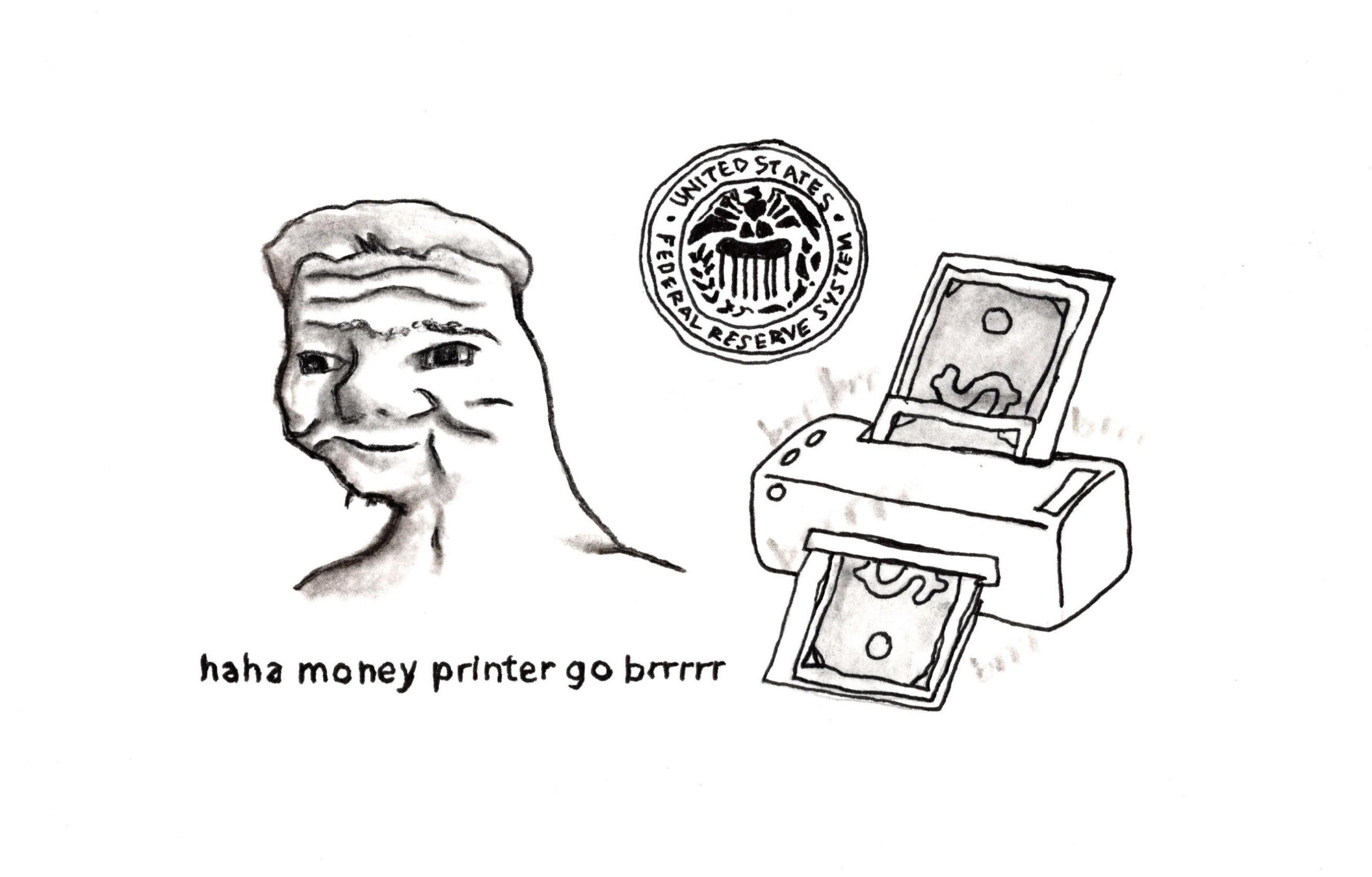

Now, however, it appears that the goal of the American company is to socialize risk and privatize profit. In 2008, fiduciary orthodoxy guided America’s economy into a frankly stupid crisis. In response, the government bailed out the most delinquent banks and corporations until the economy picked back up. What these corporations realized was that, no matter what, American taxpayers will foot the bill for their irresponsibility. Now that the economy is once again in free-fall and corporations are begging (to quote the meme) for the money printer to go “brrr,” let’s keep in mind where their true interests lie. The U.S. government should only give out bailouts in return for a stake in the business. We could realistically nationalize large sectors of the economy by taking advantage of this crisis, and we should not be afraid to do so.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Great illustration, 10/10