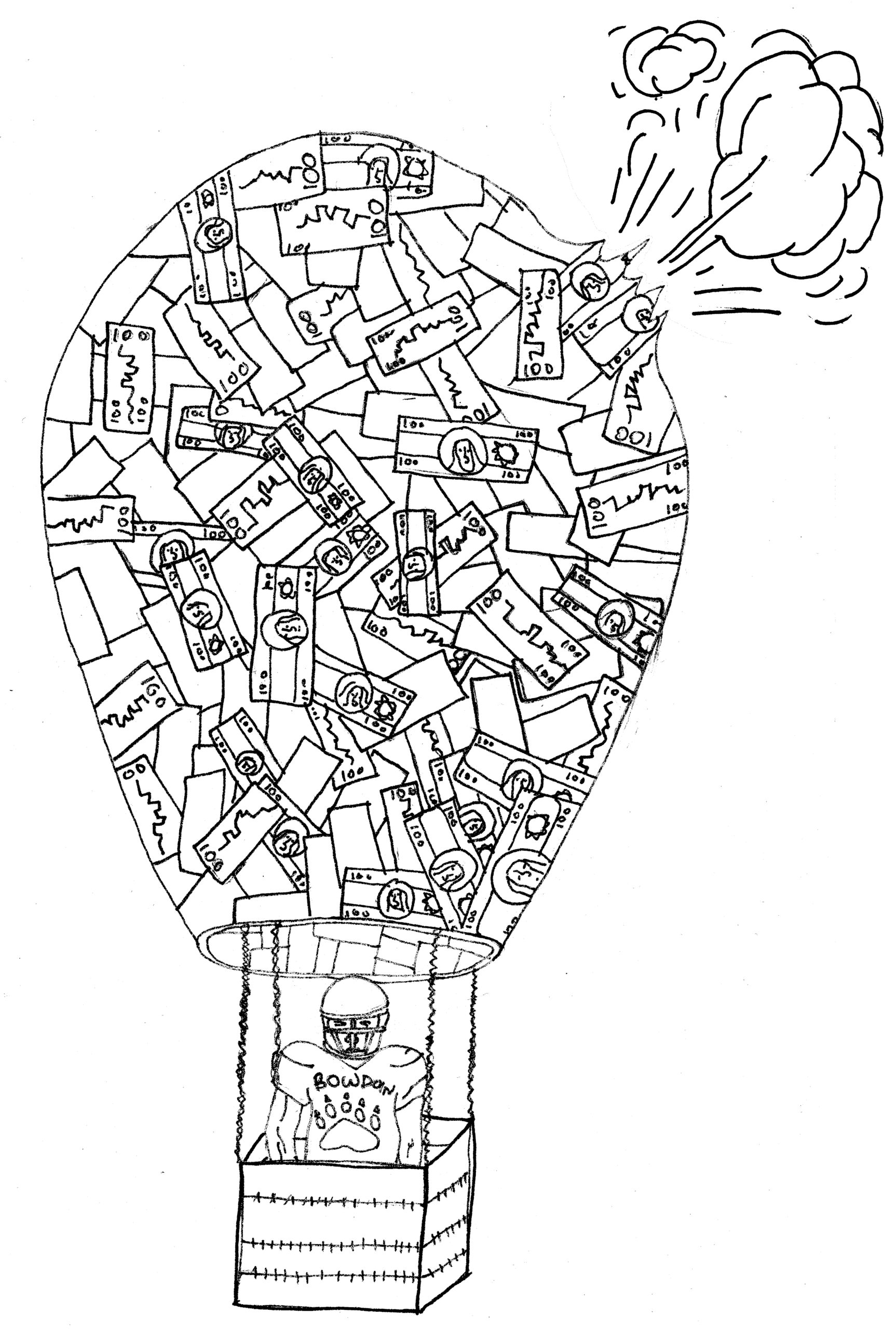

Money can’t fix everything, not even Bowdoin football

October 26, 2018

On the door to Coach J.B. Wells’ office is a poster emblazoned with the likeness of quarterback phenom Peyton Manning and the following quotation: “I wouldn’t have a single touchdown without someone to catch it, and someone to block for it, and someone to create the play, and someone to call it, and someone to celebrate it with.”

Still mired in a 23-game losing streak, the longest in the program’s history, the Polar Bears have learned the truth of Manning’s wisdom in a literal way. In a recent 62-27 smackdown against Hamilton and a disheartening 48-6 loss against Trinity, more than the Polar Bears’ record has taken a beating. Against Hamilton, three of the team’s star offensive players—lineman A.J. Mansolillo ’19, wide receiver Greg Olson ’21 and tight end Bo Millett ’21—all suffered potentially season-ending shoulder injuries. Against Trinity, the team lost another offensive staple, wide receiver Aidan Israelski ’22, to a season-ending collarbone fracture. With star running back Nate Richam ’20 still sidelined by a lingering toe injury, the Polar Bears are running low on game-ready players.

I could go into the effects that these injuries have had on the Polar Bears’ play calling (which are many) or talk about the young players who can step up to fill the gaps (which they will do, and capably). But in the end, the story is the same: the Polar Bears are once again coming to the end of a season trying their best to win, but trying even harder not to lose.

Professional and collegiate athletics are one of America’s largest and most lucrative entertainment industries because of their human appeal: the personalities that they showcase, the human dramas they display. But behind the human interest is the reality that sports are industries, complete with all the faceless statistics and humdrum mechanisms that allow industries to function.

These impersonal statistics, though, raise some difficult questions for the people who create them.

Football is an expensive activity. According to the 2017 Equity in Athletics Data analysis set, provided by the U.S. Department of Education, the 2016 football season cost the College $712,934, the most of any program. For some scope, Bowdoin spends $1,793,153 on all of its other men’s sports teams, meaning that football is about 40 percent as expensive as the other men’s teams combined.

Granted, with a roster of about 76 men, football is also the largest men’s team at the college. And when it comes to “game-day spending,” (the money spent actually conducting the games), as opposed to “total spending,” (the cost of running the program) football, while still the most expensive sport at $141,239 in 2016, is actually fairly economical in terms of its cost-per-player spending—$1,909—especially compared to some cash-cow teams like men’s tennis, which spent a whopping $11,081 per player in 2016.

But in terms of absolute spending, Bowdoin spent the most of any NESCAC school on its football team in 2016, aside from perennial-football-powerhouse Trinity, who spent about $805,000 that year. Bates, Bowdoin’s traditional bottom-of-the-barrel-buddy, spent a little over half of what Bowdoin spent, $497,755, and still finished ahead of the Polar Bears in the standings.

Since 2007, spending on football has increased by 56 percent, from $457,902 to the 2016 total. Shockingly, that increase is actually lower than the increase in total athletics spending during that period, which has ballooned a mind-boggling 101 percent from $5,004,828 to $10,042,975 in 2016.

Astute perusers of the Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act (EADA) will point out that while football costs the most of any sport, it also generates the most “revenue” of any sport, raking in $724,020 in 2016. And these astute observers would be correct, except that the term “revenue” is somewhat of a misnomer. A digression into the technical aspects of the report explain why.

In the EADA’s calculations, total revenue includes actual revenue from ticket sales (of which Bowdoin has none), advertising contracts (again, nonexistent), gifts and donations (we’ll get to that) and, finally, operating funds provided by the institution.

Bowdoin’s “revenue,” then, is the money the College provides the program to cover its costs plus any donations or gifts that the team received. If you do the math, the only outside revenue (i.e. money not provided by the College) generated by the football program in 2017 came from approximately $11,000 in gifts and donations.

Spending is understandably higher for a program that employs seven full-time coaches and must fill 14 additional recruiting spots annually, compared to the average of two. Even in the absence of wins, the spending might be justified if the team’s recruiting power contributed to the overall diversity of the campus.

But does it? Depending on how you look at it, the team is either geographically diverse or not at all. At first glance, the 2018 team has an impressive reach, with players from 23 different states (and Taipei), including Minnesota, Georgia, Illinois, Virginia, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Tennessee, Louisiana, Idaho, Missouri, Ohio, California and even Hawaii. Relative to some other men’s sports teams, 23 states looks pretty good: last season, hockey drew from 11 states, baseball from 12 and lacrosse from 17.

But relative to the demographics of the College at large, things don’t look so good. Forty players from this season’s 76-man roster hail from New England, comprising about 53 percent of the team. By contrast, in the fall of 2017 (the most recent data available), the College at large was only 38 percent New Englanders. The Midwest is likewise overrepresented, with 13 percent of the football team, but only 7.5 percent of the college, coming from the heartland. The South is about proportionately represented (11 percent on the team compared to 8 percent at the College), while the Southwest, West and international students are all underrepresented.

These numbers do not speak for themselves. First, there are other important demographic contributions—racial diversity, number of financial aid recipients and first-generation students, to name just a few—which, because the College does not make this data available for athletic teams, are either difficult or impossible to assess on a team-by-team basis.

But secondly, it’s not self-evident that sports teams ought to be expected to be demographically representative of the College at large. Of course one could argue that athletic teams, especially those that wield outsized recruiting power like football does, should be at least as geographically diverse as the campus, if not more so. On the other hand, one could argue that, at the end of the day, recruiting is about creating a team with the greatest likelihood of winning games with the personnel available, demography be damned.

This is a tricky normative debate, and it’s not immediately clear that either argument has the upper hand. What is clear is that, as it stands, the College’s spending on football is producing neither results on the field nor significant demographic gains off it. Why not? That’s the $712,934 question.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

So let’s say those 76 men on the team each pay at least 1/2 of the 68,000+ cost per year to attend Bowdoin. I’d be willing to wager that each player is paying more than that in loans or tuition, but for the sake of argument, we will say each player forks up 34,000 a year to Bowdoin. I’m not smart enough to have attended Bowdoin, but I can tell you that the number is over 2.5 Million. Subtract the money the school spends on the team and you still have a net income approaching 2 million dollars from those 76 players. Even if these guys only paid a quarter of the cost, there would still be a profit to be had. While a great institution, I’m sure most of the young men on the Bowdoin team would have looked elsewhere to continue their academic and athletic career if football at Bowdoin did not exist.

D3 Football is one of the biggest money making ventures in intercollegiate athletics there is. D3 programs are sprouting up all over the place, while D1 and D2 schools drop their programs over the cost. Why is that?