Looking back to move forward: Bowdoin’s first attempt at integration

February 23, 2018

George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives

George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & ArchivesWhen white “Freedom Rider” and Wesleyan professor Dr. John Maquire visited Bowdoin over 50 years ago, he left the message that Bowdoin students would never fully understand the struggle for civil rights until they personally and directly understood what it was like to be black in the south.

Bowdoin’s student body has certainly become more diverse since Maquire’s visit. At that time, Bowdoin enrolled only three black students and had graduated a total of only 28. Inspired by Maquire’s speech, then senior David Bayer ’64 wrote a letter to Howard Zinn, a history professor at Spelman College, a historically black women’s college in Atlanta, proposing a week-long exchange problem starting in 1963. While the exchange program came at a unique historical moment, many of the issues raised throughout are still considered today by Bowdoin students and administrators.

The letter was ultimately passed to Benjamin Mays at the historically black men’s college across the street from Spelman, Morehouse College. Mays, a Bates alum, accepted the exchange proposal. Bayer and Phil Hansen ’64 then began working with then Bowdoin Dean of Students, A. LeRoy Greason, on the program.

Hansen wrote in the letter to Mays that “this exchange is not a crusade and we won’t be carrying placards.” The goal was educational, with the aim to aid students at both colleges in acquiring a deeper understanding of racial issues in the United States and between human beings.

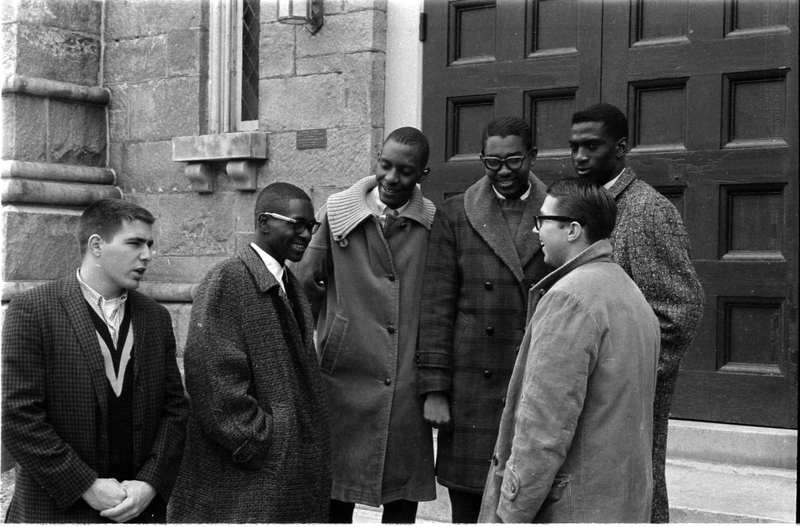

At the end of March 1963, nine Bowdoin students traveled to Atlanta for a six-day pilot of the Morehouse-Bowdoin Exchange. Six students from Morehouse drove up to Brunswick.

The students followed tightly packed schedules at both exchange sites. In Atlanta, the Bowdoin students experienced daily chapel services, panel discussions, lunch with President and Mrs. Mays, visits with the mayor of Atlanta, Georgia State Senator Leroy Johnson and the Southern Regional Council, a social hour with Spelman students, an evening with English Department Chair Richard Barksdale ’37 and his wife, and a meeting with Martin Luther King Jr. at his father’s church.

In Brunswick, the Morehouse students similarly attended daily chapel and Easter services, were received by with President and Mrs. Coles and dined in faculty homes. They sat for a concert featuring Boston Symphony cellist Yves Chardon and Professor Fred Tillotson on the piano; a talk by English Professor Larry Hall ’36 (“Jim Crow and John Doe: A Theorem of Integration”).

David Satcher, a Morehouse student and now founding director and senior advisor to the Morehouse School of Medicine, remembered his visit to Bowdoin and the genuine interest that the students had in understanding what life is like in the South.

“I remember specifically going out somewhere near the ocean and we had dinner out there and just talked into the night about what it was like to grow up in the South and to go to jail because you tried to eat at a restaurant that wouldn’t serve blacks,” said Satcher, “[Bowdoin students] had a really great interest and it was almost as if they were living the experience with us.”

A Orient editorial said that the exchange program would only be worthwhile if Bowdoin students could come to the realization that they are integral to the struggle for full equality.

“It has meant nothing except an exchange of bodies of different color between two different schools if we are not aware of the problems we face as well as those of the Negro,” the Editorial Board wrote.

Satcher recalls the experience as a special one, since prior to Bowdoin he had only been to segregated schools. “I hadn’t had much association with white students at all, back in that time,” said Satcher. “To see the kind of support and enthusiasm that we experienced at Bowdoin was a special experience.”

In 1963, the Orient interviewed one of the Morehouse students, Ray Luandy, about his experience, to which he said the length of the program was its biggest obstacle. “The problem of race tolerance is essentially one of education and how much education can take place in a week? I think perhaps a long-range proposal—a semester or a school year would be more beneficial,” said Laundy. “Then the exchange students would have the chance to see what the other side is really like—after the novelty wears off.”

Similarly, the Orient reported that Laundy felt that scheduled activities did not allow for the exchange students to experience the College for themselves. “The visitor doesn’t really get a chance to see things in a normal setting. We have been given a schedule of things to do and see, but the great degree of organization seems uncomfortable at times,” Laundy said.

Ultimately, the pilot program was deemed successful and the following year a semester long exchange was initiated in the spring of 1964 and continued through 1967.

The next spring, around six students participated in the exchange. Charlie Toomajian ’65, who participated in the six-day visit, was among the first batch of students to participate in the 1964 semester long program.

In an interview with the Orient, Toomajian remembered his experience as one of true openness. He felt that he was truly a part of the Morehouse experience by going to classes, civil rights meetings and informal conversation. “I felt fortunate to be asked to be part of it. I was working with [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] and with the local things and met with Martin Luther King a few times, and helped with strategy planning with the leaders from the college,” said Toomajian.

Toomajian also remembered the hostility he experienced as part of integrated groups. In a piece written for the Brunswick Record in 1964, he wrote that students experienced many “baleful stares, angry threats, and racial epithets” when they were in integrated groups. While in Atlanta, Toomajian participated in restaurant sit-ins. He recalled one instance when he and other students were chased out by armed restaurant staff.

“We sat down, and instead of going through the normal routine, he just came out from the back with his staff and started waved the hell of out an axe handle. He chased us out into the parking lot, into the traffic,” said Toomajian.

Toomajian also recalled an incident on his way back to Bowdoin. His friend, who was black, was accompanying him to the airport. From Morehouse they took a black-owned cab company, but it only drove them to the city limit. They had to switch cabs for Toomajian to make it all the way to the airport. “But, then the person who was black wasn’t able to continue on the trip, because the white cab would not take anyone who was black. It was just an ungodly situation. Just absolutely crazy,” said Toomajian.

In Brunswick, the Orient pushed students in a 1963 editorial to actually engage with the exchange students from Morehouse: “How many made a serious effort to meet and talk with the Morehouse students about the basic problems of Negro equality in a white dominated society? And, we don’t just mean simply smiling politely at one on the way to class or pointing out one of them to an even more indifferent friend.”

In order to facilitate student interaction the 1965 Orient interviewed some of the students from Morehouse. One of the students interviewed was Freddie J. Cook. Cook returned to Bowdoin’s campus in 2015 by invitation of the African-American Society to speak about his experience. Having grown up in a poor family in Atlanta, Cook said that attending Bowdoin was an opportunity to escape poverty. However it was also difficult to adjust to Bowdoin because of its radically different environment.

Cook recounted positive experiences: he learned to play bridge in Moulton Union, remembered excellent relationships with professors, attended his first toga party at Theta Delta Chi and enjoyed discussions in English literature and economics courses.

Cook also remembered some of the struggles he experienced at the College and found it difficult to adjust because of its radically different environment.

“I had boundless ambition to gather me, yet I soon found myself lapsing into depression.” He then spent a lot of his time in isolation, writing poetry to overcome the shock of Bowdoin. Cook was initially surprised that many Bowdoin students had maids, since his mother worked as a maid and nanny for a Coca-Cola executive. His mother ended up quitting her job after one of the boys she cared for returned from college, called her a racial slur and refused to apologize. At the time, she was making $1 an hour.

At the time, Morehouse students at Bowdoin maintained the same tuition they had at Morehouse. Cook, on financial scholarship to cover $267 tuition per semester, told the Orient in 1965 that there were major inconsistencies in transferring grades from the 100 point scale at Bowdoin to the 4.0 scale at Morehouse.

“A 70 to 79 here is only a 2.0 at Morehouse. A student on the honor roll at Bowdoin wouldn’t necessarily make the honor roll at Morehouse, yet the administration down there won’t make allowances for this, and as a result, although I’m making decent grades here, I’m in danger of losing my scholarship from Morehouse,” said Cook, “if this rigid policy at Morehouse persists, I feel the exchange program should be ended because it only results in the students from Morehouse being penalized.”

George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives

George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & ArchivesWhile the exchange ended when President Coles retired in 1967, it paved the way for further initiatives, like Project ’65, a student-organized high school outreach program that focused on expanding access to information and recruiting black students to apply to the College.

Toomajian, upon return to Bowdoin, helped found BUCRO, the Bowdoin Undergraduate Civil Rights Organization, an umbrella organization that encompassed Project ’65 and the Morehouse Exchange Program to ensure coordination between the different civil rights groups.

“It was a time when there was a lot of student activity. It was a time when we were trying to figure out where we stood with the Vietnam War—when Martin Luther King was active,” said Toomajian. “It was a time when there was a lot activity on the Bowdoin campus and a lot of discussion. Very honestly, when I look back at those times, I’m very proud of the way that the College, at that time, did things.”

The Morehouse-Bowdoin Exchange Program made many of its participants feel emotionally fulfilled. “I think what Bowdoin and experiences like Bowdoin did for many of us was to help us to really understand people of a different race, and even a different culture in terms of the North and the Bowdoin experience,” said Satcher.

It is educative, though, to consider how much the exchange ever reshaped campus culture. In recent years, students have dealt with bias incidents ranging from a “Gangster”-themed party to swastikas being drawn on school property. A program like the Morehouse-Bowdoin Exchange, completed 50 years ago, could not be expected to begin to solve racial tensions on campus, especially given its limited scope. The question remains, though, how will Bowdoin’s campus change, or stay the same, in the next 50 years?

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

This is a fantastic article; one of the best I’ve ever read in the Orient. I have been disappointed over the past 20 or so years as the College seems more focused on the bottom line (e.g. being run by businessmen and not academics) and less on the Common Good. Bowdoin used to think big; especially in the Coles era.

Excellent article on information that should be shared with high school students in the African American Diaspora. I say this because it is important that these students know more about their history as they go about selecting colleges and as they continue to gain self esteem relative to the history and accomplishments of their ancestors.