African in America: transforming a country that doesn’t love me

February 9, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

“If black people hate it here so much, maybe they should just go back to their country.” A white girl in my high school allegedly made this remark while I was reciting an original poem about Trayvon Martin during our weekly assembly meeting. A cluster of students gasped as soon as she made the comment. She was implying that while I was born here and my family put its sweat and tears into America’s progress, this country still wasn’t my country. Her comments were hurtful then, but they don’t phase me today.

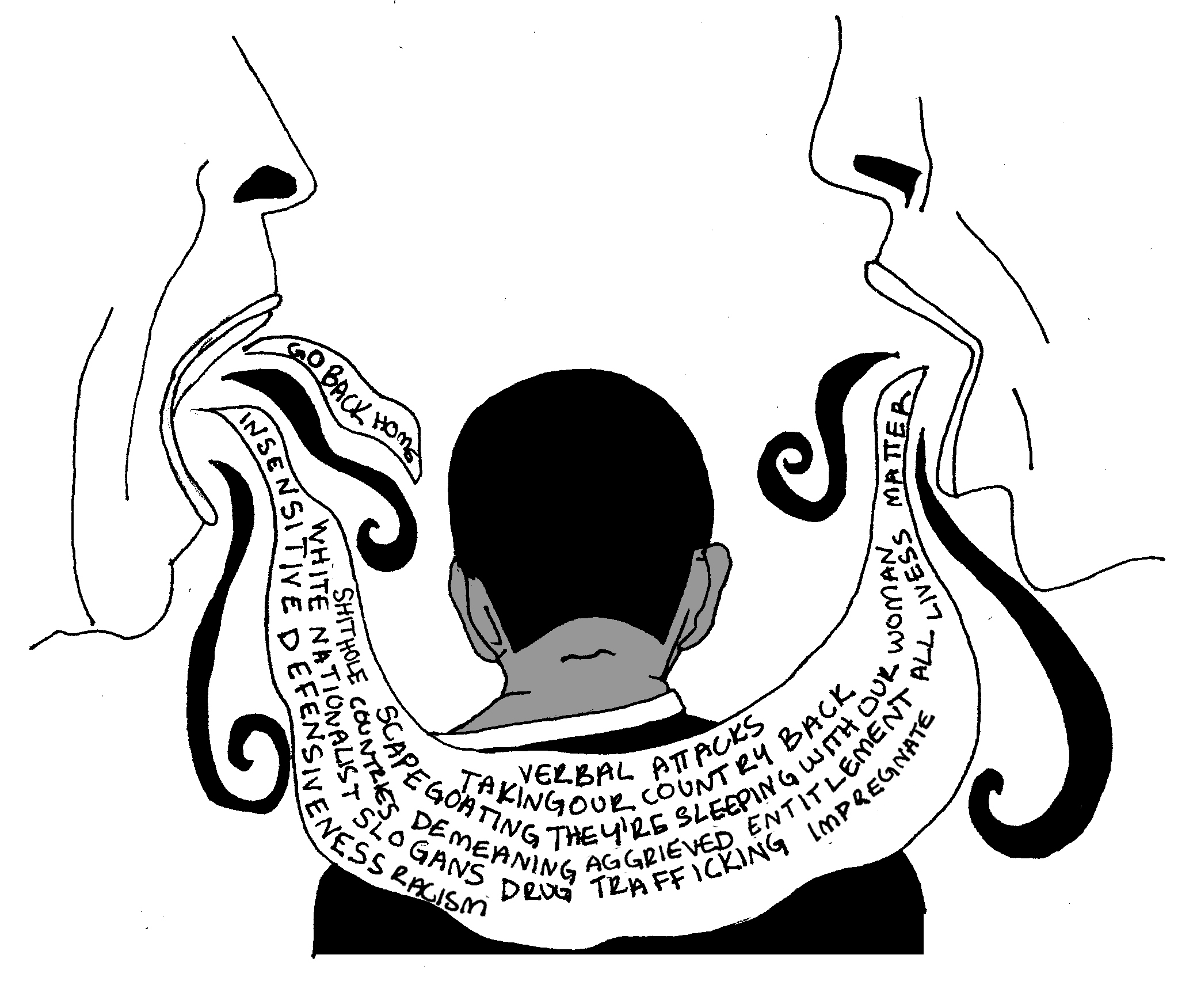

I’ve habituated myself to the racial undertones of social relations—the palpable aura weighing down on my shoulders every time I walk through Bowdoin’s campus. After attending a predominantly white high school, I imagined college to be a walk in the park. I didn’t consider the implications of attending a college in Maine, the whitest state in the U.S. Whiteness alone is not a source of fear, but rather white fragility: the state in which the slightest amount of race-based stress triggers insensitive defensiveness from certain white people. Here in Maine, I’ve heard all the white nationalist slogans—from “taking our country back” to “all lives matter”—that try to legitimize white privilege instead of addressing the unfair challenges people of color face.

Lately, Donald J. Trump—who is somehow the U.S. president—has become the most flagrant example of this white fragility. It is difficult to keep up with his frequent remarks about race and ethnicity, but he is only one of several American figures playing into white aggrieved entitlement.

Trump’s friend, Governor Paul LePage of Maine, has made comparable statements, often scapegoating black and Hispanic people for Maine’s drug trafficking problem. In January 2016, LePage said, “guys by the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty” come to Maine, “sell their heroin, then they go back home. Incidentally, half the time they impregnate a young, white girl before they leave.” In the most demeaning way, LePage links black men to drug trafficking and employs the “they’re sleeping with our women” trope to justify his verbal attacks against them.

LePage’s rhetoric draws parallels with the anti-miscegenation arguments that white Southerners employed to justify the lynching of black men in the 20th century. During the presidential election in 2016, Trump channeled his friend’s language by implicitly correlating Maine’s Somali refugee population and the state’s crime rate, even though the acting police chief of Lewiston—a Maine city with a large Somali population—said that the crime rates have gone down in Lewiston and across the state.

The racist and xenophobic scare tactics of right-wing populist circles are concerning, but they are not new. The sad truth is that racial inequality is part of America’s history. I was nearing the end of my winter break trip to South Africa—a nation similarly plagued by the myth of non-racialism—when I overheard the latest episode of white nationalism on the news. Trump stated that he didn’t want immigrants from “shithole countries,” citing Haiti, El Salvador and African countries as examples during a white House meeting with congressional leaders. Rather, he preferred immigrants from countries like Norway to enter the U.S. When Trump singled out Norway, South African comedian Trevor Noah had a clever response: “He didn’t just name a white country, he named the whitest—so white they wear moon-screen.”

But let’s face it; Norwegians don’t even want to migrate to the U.S. like they used to. Norwegian immigrants are currently the third smallest group of migrants in the country based on the latest Census Bureau. Data also shows that Norway boasts a far better quality of life than the U.S., as it has topped other countries in the U.N.’s Human Development Index for several decades. In theory, Norway would have been on Trump’s “shithole” list over a century ago, since Norwegian immigrants were significantly lagging behind other European immigrants in earning potential in the U.S. until the post-WWII era. In reality, Trump views Norwegians as desirable immigrants because they are white. He wants whiteness to be a requirement for immigration to the United States.

As the son of black immigrant parents—from the “shithole” country Nigeria—I don’t feel wanted in Trump-era America, especially in Maine. I never walk down the streets of Brunswick past a certain time. I pull out my wallet every time I enter a store. I came to Maine to attend one of the best liberal arts colleges in the nation, yet the state’s governor thinks men who look like me are drug dealers. Still, there is hope that discourse about racism—not race—will hit the mainstream one day. I look forward to the day when politicians comfortably call Trump and others “racists” and admit that racism exists in America. Until then, I remain a hyphenated American, a Nigerian-American, who boldly provokes thought in hopes of transforming a country that doesn’t love me. If you’re reading these words with a new discomfort, I’m happy for you. Own that discomfort because it’s only a fraction of what black people in America have been feeling for a long time.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: