You goose!

October 20, 2023

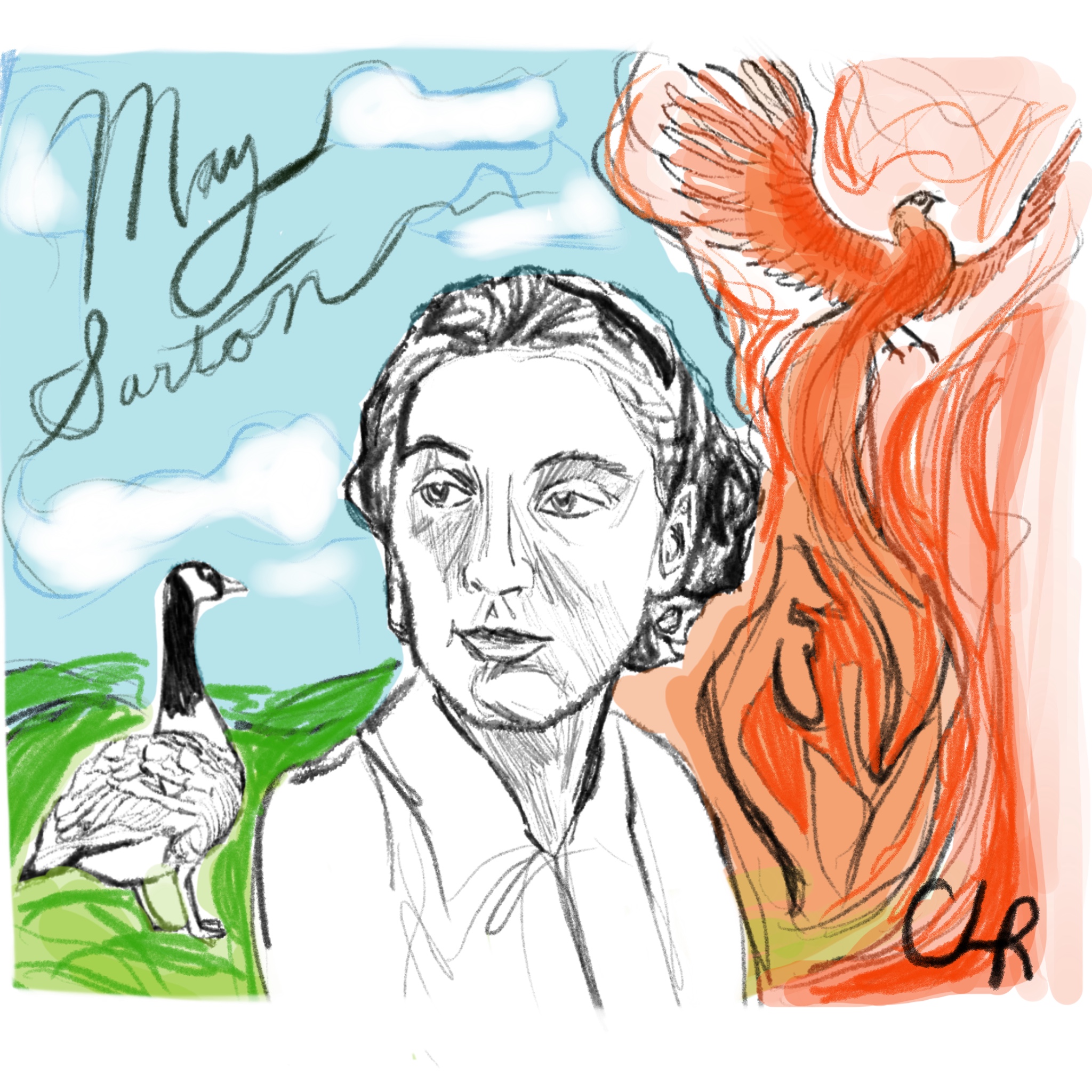

Lauren Russler

Lauren Russler“Once she turned on me in apparent fury and shouted, ‘You goose!’ and then, before I had time to burst into tears, added in an explanatory tone, ‘That’s a metaphor.’” – May Sarton, “I Knew a Phoenix”

At the Shady Hill School in Cambridge, a young May Sarton was met by “poetry incarnate,”

which took the form of a brilliant English teacher. Mrs. Hocking commanded her students’ attention and encouraged them to take literature and poetry to heart. “We learned poems by osmosis—the only good way,” Sarton wrote.

In one particularly instructive incident, Mrs. Hocking administered an aviary object lesson in metaphor and simile, teaching Sarton “that metaphor explodes, and simile is pale beside it.”

If Sarton was a goose, clumsy and imprudent, then Mrs. Hocking was a phoenix: sophisticated, enchanting and vibrant. So arose the title of Sarton’s 1954 New Yorker piece and 1969 collection of essays.

“I Knew a Phoenix” was probably Sarton’s most successful work of prose, though she was already a prolific writer: By the time of its publication, Sarton had nearly a dozen poetry collections and a number of novels already under her wings. Having found herself flying, Sarton reflected upon the literary phoenixes she had known.

In biographer Margot Peters’ 1997 chronicle of Sarton’s life, she writes that “I Knew a Phoenix” emerges as a defense of the notion that “a young person nurtured by extraordinary people cannot help being extraordinary herself.” In the body of extraordinary people in question, Mrs. Hocking sits among the likes of Aldous Huxley, Sylvia Plath, W.B. Yeats, Willa Cather, W.H. Auden and Simone Weill who shaped Sarton into the writer she would become.

Sarton’s recollection of Mrs. Hocking’s admonition is itself a testament to both women’s creative voices. The sentence is innovative—it is a sentence containing sentences of dialogue that lend to an image of Mrs. Hocking. At first, she is in a state of “apparent fury,” but her ultimate goal, we later find, is “explanatory.” The sentence is humorous and immersive. It is a winding story. It is poetic in form and is perfectly placed in an essay on the study of poetry. If this sentence serves as any proof (and I would contend it does), then Sarton’s literary inspirations have done diligent work in teaching her to write.

One of May Sarton’s greatest inspirations was Virginia Woolf, whom she also counted as a close friend. Absorbed writers through and through, the two recounted their friendship in diary entries that tell of novels deconstructed and stories shared over tea times and trips to the London Zoo.

In fact, Sarton and Woolf were both prolific diarists. But Peters posits that the two had different goals for self-reflection:

“Professional writers like Sarton and Anaïs Nin, of course, wrote ‘privately’ to publish, quite a different thing from Dorothy Wordsworth’s journal keeping, Virginia Woolf’s working diary, or Sylvia Plath’s journals.”

All the women share, in their diaries, a powerful ability to contemplate their lives in a manner often immensely self-critical yet undeniably honest. They all admit uncertainty about belonging in their respective worlds, whether London, Paris or New York.

Peters certainly has a point, though, when it comes to Sarton’s more “private” nature. In “Journal of a Solitude,” a sixty-year-old Sarton narrates a year of relative isolation at her New Hampshire home. She details the exhaustion of maintaining romantic relations or entertaining guests. “I hate small talk with a passionate hatred,” she wrote in September.

Sarton resolves by the end of the year that life may be best spent in solitude. “Perhaps the greatest gift we can give to another human being is detachment,” she concludes.

In her 1968 memoir “Plant Dreaming Deep,” Sarton reflects upon renovating the New Hampshire farmhouse that became her permanent home by the time of “Journal of a Solitude.” Years after “I Know a Phoenix,” she finds that metaphor still proves to be a powerful tool.

“We have to make myths of our lives; It is the only way to live them without despair. This is not to dramatize so much as to look for and come to understand the metaphor that reality always holds in it,” Sarton writes.

Sarton came out in 1965 and her reflections on navigating relationships with women made her one of the more prominent lesbian and feminist writers of her time. But despite her many lovers, Sarton lived alone in her final years, both at her New Hampshire farmhouse and, at the end of her life, in York, Maine. She passed away in 1995 but after a stroke in 1990 had difficulty typing or writing by hand. She continued writing by recording cassette tapes for transcription, thus producing diary entries until her final days. She never ceased seeking metaphors in her reality.

So Sarton was never truly alone, despite her solitude, for she had Woolf and Plath and Mrs. Hocking—her phoenixes—always with her. And to this goose, May Sarton is a phoenix.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

This column is a total joy.