Escaping a riptide

November 3, 2023

Henry Abbott

Henry Abbott“And I’m starting to see how as time gains momentum my choices will narrow and their foreclosures multiply exponentially until I arrive at some point on some branch of all life’s sumptuous branching complexity at which I am finally locked in and stuck on one path and time speeds me through stages of stasis and atrophy and decay until I go down for the third time, all struggle for naught, drowned by time.” – David Foster Wallace, “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again.”

The overwhelmed writer responds in a sort of compositional panic with words that rush out and run on: in David Foster Wallace’s case 66 in a row punctuation-free with no commas to indicate a pause or slow the acceleration of the spiraling mind such that one imagines the pen rushing faster and ink smudges trailing behind until the necessary respite of a comma, a breath of air, and then pulled under again, “drowned by time.”

The humorous writer responds to such a panic by admitting (but not abandoning) his tendency to take life too seriously. For example, he may take the experience of a vacation cruise, embarked on for a Harper’s Magazine journalistic assignment, and twist it existentially.

David Foster Wallace’s resulting story is a testament to the comedic potential of authorial dread so overflowing with wit that many of its best lines trickle off its pages and fill 137 footnotes. In “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” Wallace recalls caviar tasted, passenger talent shows watched and a Conga line joined “(very briefly).” He finds that cruise lines implement an eerily “authoritarian” control over passengers’ pleasure. No amount of one’s own “adult consciousness and agency … choice, error, regret, dissatisfaction, and despair” can get in the way on a cruise. “You will have no choice but to have a good time.”

As Wallace begins worrying about how to decide what fun actually is and how to remain certain of the path upon which his decision will “lock” him, time gains momentum. His stress compounds as the sentence builds. The independent clause seems uncertain—as if it has just come into independence. Unaware of what to do with its agency, it rambles awkwardly like a young adult asked too serious or prying a question about their place in the world.

This is a sentence that demands to be reread. Upon reconsideration, its structural spiral is better unwound; its initial franticness made less neurotic.

In her New York Times review of the 1997 collection in which this story lies, Laura Miller characterized Wallace’s style as “distinctive and infectious … acrobatic cartwheeling between high intellectual discourse and vernacular insouciance.” Cartwheels perfectly encapsulate this sentence’s swift spinning between philosophy, absurdity and wit.

Yet Wallace is anything but insouciant. Take “sumptuous branching complexity,” three words carefully chosen to construct life’s opportunities as both rich with potential and troubling to navigate. These words are not indifferent, and without them, one cannot explain Wallace’s compounding stages of stasis, atrophy and decay. His phrases manage intentionality and poignance without any glibness or didacticism.

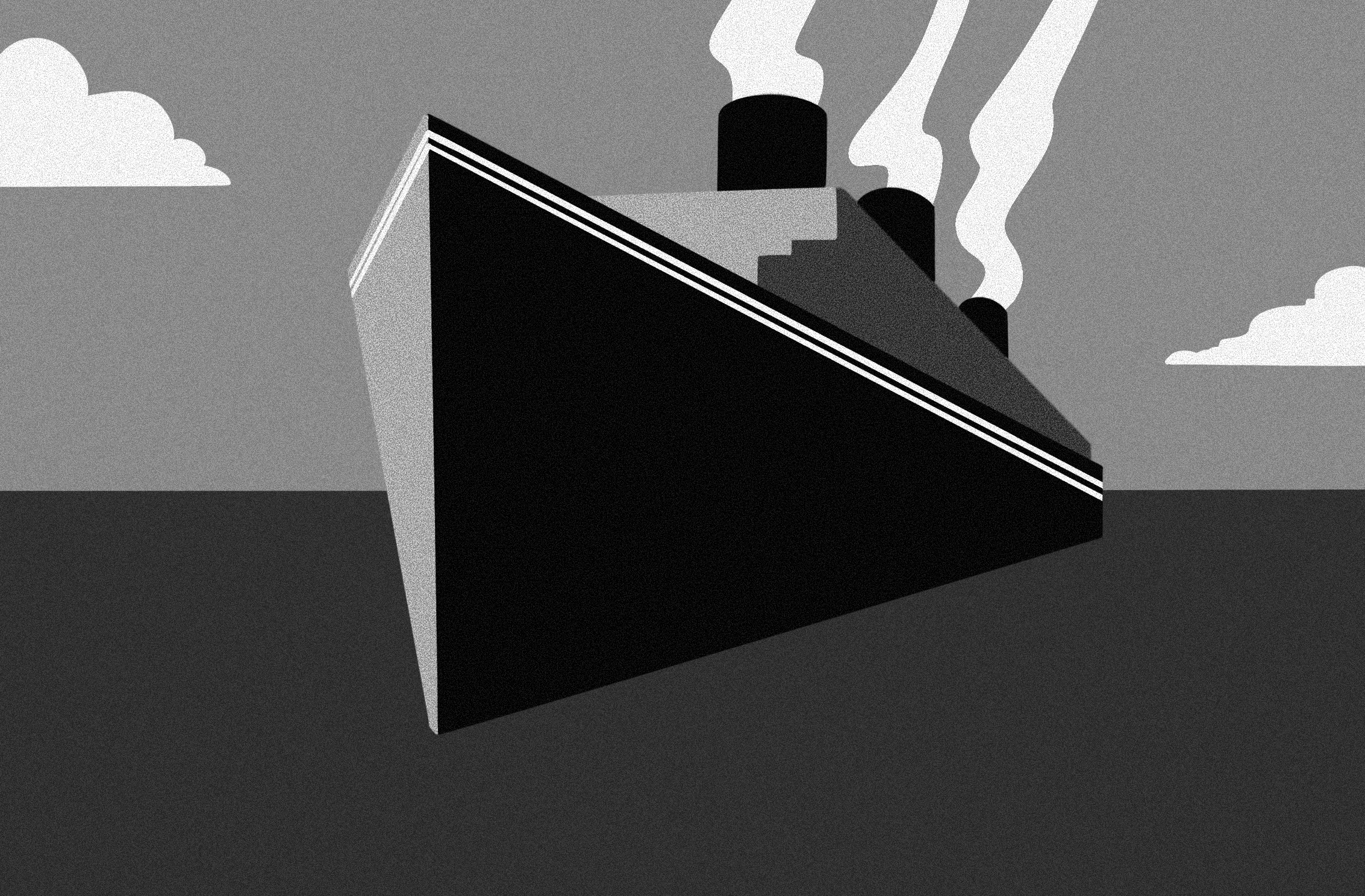

This sentence’s “drowning” torrent of words—structurally reminiscent of a riptide—further dampens the label of “vernacular insouciance.” Forceful and uncontrollable, riptides are most dangerous to those who try to swim against the current. To best escape a riptide, one must succumb to it. Attempt to fight against the use of “and” six times between periods and you will drown.

I was introduced to Wallace in an aquatic tale of a different nature. In “This is Water,” a commencement speech Wallace gave in 2005 at Kenyon College, he advises the liberal arts college’s graduates not to bury the importance of “simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over:

‘This is water.’

‘This is water.’”

“A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” was originally entitled “Shipping Out,” a hint to Wallace’s quasi-journalistic assignment to the cruise. But this early name also implies a sense of choice, once made, as inescapable in precisely the manner agonized over in this sentence.

In the nine years between “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” and Wallace’s commencement address, his view of water shifts. Here are 73 words in which currents are strong and malicious. Here, water enacts despair. “This is Water” raises no possibility of drowning. There, the riptide has subsided, and water is still. We are the agents, the conscious ones, and we float through water fearlessly. We grow so unaware of it that we must remind ourselves it even exists.

A cruise is dangerous, ultimately, because it involves a relinquishing of consciousness. “Shipping Out” means placing agency, pleasure and fun into the hands of the captain and crew. Regaining consciousness allows one to escape the riptide (or the unbearable Conga line or talent show) and relish the simple discovery that this is water.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: