‘The Wicker Man’ and western anxieties: exploring the modern resonance of pagan horrors

November 9, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Shona Ortiz

Shona OrtizIn retrospect, I should have known that “The Wicker Man,” billed as a relaxing, post-midterm movie screening for my Human Sacrifice course, would be anything but. When shots of pagans openly copulating in a graveyard and a cake in the shape of a young sacrificial victim popped up in the first 15 minutes I was certainly not relaxed. “The Wicker Man,” a 1973 cult horror film that was subject to an unspeakably terrible remake in 2006 (sorry, Nicholas Cage), has an unsurprisingly minimal fan base, as is the nature of many “cult” films. My entire class seemed disturbed, and I began to wonder what exactly it was that troubled me.

I quickly eliminated the seemingly-Vaselined lens and hokey dialogue as hallmarks of 1970s cinema that didn’t affect this 21st-century audience in the same way. However, when I looked into the critical reception of the movie, I began to understand that director Robin Hardy was perhaps tapping into something that not only transcends generations of viewers, but aims to poke a bear of particularly Western origin and construction; the movie fundamentally complicates the binary of “good” and “bad” religion. While this certainly disturbed past audiences, the reactions of modern viewers have highlighted the renewed meaning of this binary in a post-9/11 world. Examining the film in light of the discourse surrounding the “War on Terror” that has dominated much of our lives, including the distinct accusations of barbarism on both sides, reveals that while the locus of horror remains the same, for some, the movie takes on a more modern, chilling significance.

Horror director and actor Eli Roth explains this shift in connotation by discussing the modern understanding of this same binary of “good” religion and “bad.” In an interview with IGN entertainment in 2013, Roth speaks to the continued resonance of the movie. “I think what makes it so incredibly relevant,” says Roth, screwing up his face, curling his fingers and raising his hands to the camera, “is the theme of devout, religious belief. That any kind of religious zealot that would kill in the name of their own religion.”

He goes on to distinguish those who possess “religious ideals” from those who treat religion as an all-consuming lifestyle. This distinction is entirely warranted, and Roth’s description of just how difficult it is to sway someone who is firmly entrenched in their beliefs has increasing religious and political relevance five years after his interview. Roth provides a real-world example for this previously theoretical distinction.

“I remember watching ‘The Wicker Man’ and thinking that it was so similar to those al Qaeda videos,” he continued.

I paused the video and thought for several seconds, scanning my brain and then the internet for the comparison he could be drawing. It is an important distinction to draw that their “ideology,” which Roth references several times in the interview, specifically “denounces” the vicious beheadings publicized by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian jihadist. While he was loosely associated with al Qaeda, fissures between his followers and the group heightened when he adopted the practice of beheading in 2004. While I am not in the business of defending al Qaeda, Roth’s omission points to a larger problem in the rhetoric surrounding good vs. bad that leaves no room for the nuance on either “side.” Roth identifies the heart of what disturbs him about both “The Wicker Man” and al Qaeda as “their ideology.” As he explains, “Ideology can be a terrifying thing when it’s applied to someone who fully will do anything for it.”

Roth’s attitude mimics the trajectory of the movie. “The Wicker Man” constructs a perfect dichotomy between the savage pagans and the perfect protagonist—order-loving, Christian and virgin Sgt. Neil Howie lives in stark contrast to the inhabitants of Summerisle, the pagan island he visits to investigate the disappearance of a young girl. At the climactic ending, Howie’s Christian prayers shouted over the roaring flames, bleating goats (just watch it) and the singing of the island inhabitants presents the starkest visual and aural contrast in the film. Howie implores the islanders as they prepare him for (spoiler!) ritual sacrifice, screaming, “Think about what you’re doing!” The contrast here shifts from one between two religions to one between reason and barbarity, with Christianity firmly situated in the former category.

Translating this contrast onto Roth’s example, Americans are the arbiters of reason, and al Qaeda are the barbaric cult followers to whom reason has no appeal. Implicit in this distinction is also a contrast between thought as a sign of progress, modernity and civility and action as visceral, unthinking and barbaric. Upon considering the state of our nation and the most recent attacks carried out in the name of religion or against religious believers, we must take stock of America’s position on the high horse of reason and centrism and fundamentally re-evaluate.

In identifying these overlapping binaries, I am taking no firm stance. It is interesting, however, to understand the anxieties that a movie as niche and as haphazardly shot as “The Wicker Man”—actors were apparently forced to film the climax of the movie while on the run from studio executives and to read their lines off of sheets hung from nearby cliffs—can evoke in its viewers regardless of their age and the cultural context in which they view the film. The pervading fear that Roth illuminates, that “you can’t fight it, there’s nothing you can do against it,” is perhaps not universal, but is not a relic of the past, either. Hardy’s panning shots of lush countryside and almost comical dialogue even in the most violent parts of the movie draw their own contrast and highlight the unsettling quality the film creates.

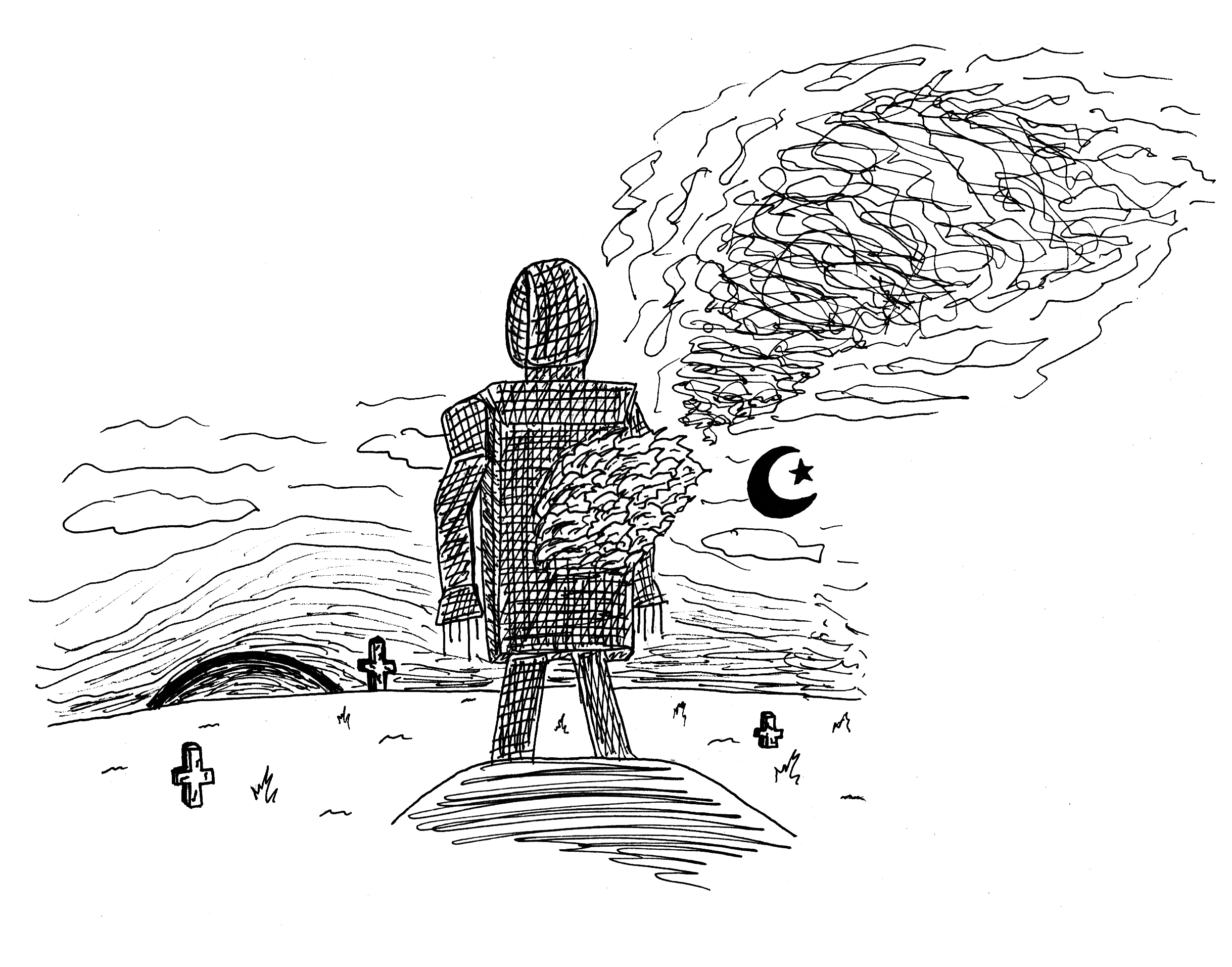

For viewers past and present, the kitschy paganism in “The Wicker Man” perhaps throws into relief the religious extremes of today, both national and international, that leave people disquieted long after the credits role on the burning wicker effigy against a blazing sunset.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: