Material messianism: ‘Waiting for John’ and the ‘cargo cult’

November 30, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Molly Kennedy

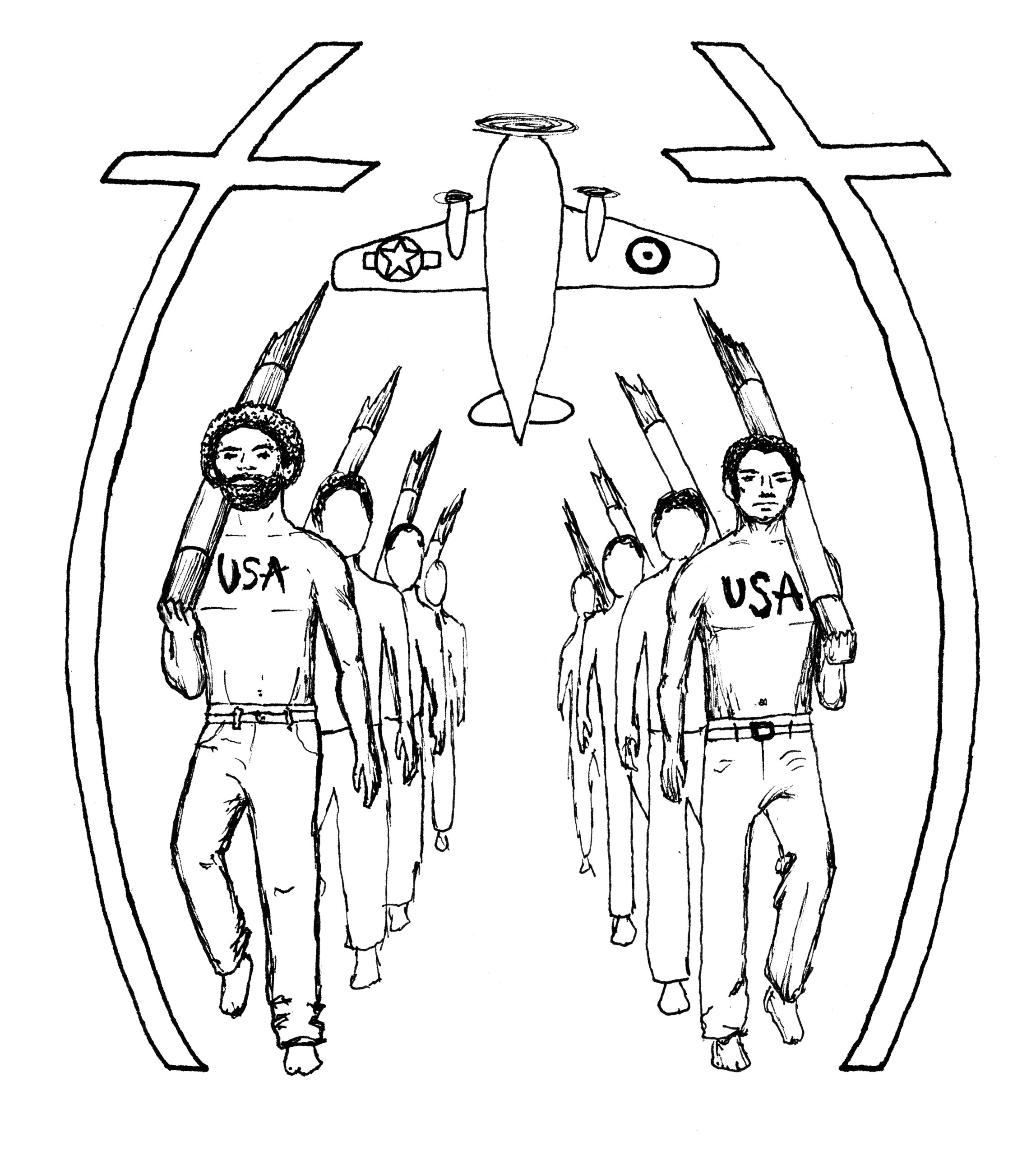

Molly KennedyAs a documentary and irony enthusiast, I spent Black Friday watching “Waiting for John: An Island Cult Worships American Materialism.” The 2015 documentary centers on the John Frum movement on Tanna, an island in the archipelago of Vanuatu. More commonly known as a “cargo cult,” this minority religion revolves around the figure John Frum, said to be a soldier who visited Tanna during World War II bringing promises of American materials, or “cargo.” Belief in his imminent return sparked the performance of U.S. military rituals, including drills and flag raising ceremonies to maintain belief in John’s return. The connection between this near-extinct religious practice and “Black Friday” is obvious. In this article, I am more interested in teasing out the latent stereotypes about religion and ritual that come to the fore in depictions of these “cargo cults.”

The John Frum movement has its greatest stronghold in the village of Lamakara, in southern Tanna. Though Chief Isak Wan maintains a firm belief in John’s return, many villagers have left the movement for Christian alternatives on the southeast coast. “Waiting for John” highlights a hierarchy of legitimacy for religious groups that extends far beyond Tanna to our own Western conceptions of religious practice.

The John Frum movement entails a curious appropriation of Western practices. From footage of a 1960 docuseries, “The People of Paradise,” voice-over favorite David Attenborough explains early American rationale for these cults. With America using the island as a military base in battles against the Japanese, Attenborough points out that islanders could not help but marvel at the very “cargo” that has come to form the basis of their religion. Imploring his Western audience to place themselves in the islanders’ shoes, he argues that, eventually, “it dawns on you: this is the secret. The white people are doing this as a sort of ritual designed to make the gods send the goods to them, the cargo.”

In this 1960 documentary, the islanders are limited to a ritual lens through which to see the world. The implication is, moreover, that this is a less sophisticated worldview. As Attenborough suggests, the only way the islanders can conceive of American military practice is through a potential communication with the gods. And while this certainly was one facet of their initial belief, the reality of American presence in 1942—following the first John Frum prediction in 1940—lends this belief to historical and colonial legitimacy. For John Frum believers, their belief is based in fact—to some extent, they are correct. What’s more, with the arrival of colonizers in 1774, Western influence has been present on the island for a very long time. While it is important to assess these beliefs as primarily spiritual and religious, as practitioners themselves view the movement, it is also important to note that the “spirit of John Frum” is closely intertwined with the specter of colonialism that, while no longer physically occupying the island, certainly maintains a firm grip even from oceans away.

There are two angles of analysis for the material presented above. The first, perhaps more intuitively, is comparative. This line of analysis links the belief in Jesus Christ the messiah and the belief in the return of John Frum. Theorist John G. Melton has identified the processes of “spiritualization” as a crucial mediating factor for religious movements whose prophecies are subject to doubt. Reconceptualizing an anticipated physical or material act as a spiritual occurrence can work to reaffirm the belief in the prophecy and its fulfillment. As filmmaker Jessica Sherry notes, all believers of the John Frum movement maintain that “John is a spirit.” This rationale holds true for the messianic elements in Christianity as well. In a more secular sense, the movement’s replication of American national rituals highlights the overwhelming, almost “religious” hold material culture has on our lives. Other articles have taken this tack to contextualize “cargo cults” within modern American materialism.

A second angle, however, perhaps presents a more nuanced conclusion than direct comparison. For as Melton also acknowledges in his 1985 article, messianic prophecy is not the sole tenet of any one religion. Though it is certainly a facet of worship, a given movement “must also develop a group life within which ritual can be performed and individual interaction occur.” The John Frum Movement must be taken for more than its prophetic component. As one village member, August, explains, “We live here in Lamakara a very peaceful life. Chief Isak leads us all. He has rules for many things so that we live according to our traditions.” Brothers Naunoun and Joseph cite similar traditions and the importance of living “as our ancestors lived.” The weekly worship, daily flag-raising and orderly marching lend structure and coherence to village life in their present iterations, even as they are oriented towards a future of prosperity that may never come. “John told us: ‘OK. One day something will come to our people,’” says Chief Isak Wan. This promise, left vague and entirely without temporal or material specification, works to sustain the present as much as it does belief in the future.

Internal fissures and external pressures from Christian movements in Port Resolution and Sulphur Bay threaten to extinguish the John Frum Movement. Moreover, the emphasis on “tradition” and “custom,” reveal not only the belief in John Frum’s return, but also attests to the constitutive nature of religion and its undeniable social function. As Sherry’s film suggests, the John Frum movement can tell us a lot about the way we construct legitimacy, history and most importantly religion and ritual. Rather than tied to a fictional realm or spiritual realm, it is clearly the product and process of real, historical encounters. As Melton puts it: religion and ritual operate “within a complex set of beliefs and interpersonal relationships.” I would strongly recommend “Waiting for John” as a thought-provoking watch.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: