Maine’s Franco-Americans: a short history

November 9, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Sara Caplan

Sara CaplanThis past summer, as I was inspecting storm drains in a neighborhood of Sabattus, Maine, an elderly man approached me from his driveway. His name was Marcel, and though he was initially only curious about what I was doing, our conversation soon blossomed into a discussion about his life. He had grown up in a large farming family, had served in an army battalion after World War II (the same one as Elvis Presley, believe it or not) and now spent his days going on long walks and tinkering in his garage.

What struck me about Marcel, however, was not his remarkable story, but his accent. When he spoke, he sounded like someone from Québec. Instead of English swears, he would mutter “crisse” every couple of sentences. I asked him if he had spoken French as a child, and he nodded. He told me how his parents had immigrated from Canada to central Maine, where they had him and all his siblings and where he had stayed his entire life.

Marcel’s experience is not atypical in Maine. Though our state boasts a large population of English-Americans, the second largest group are the Franco-Americans, a catch-all term for people of French descent, which includes people identifying as French, French-Canadian, Acadian or Franco. Though we share this heritage with New Hampshire, Vermont, northern New York and, to some extent, southern New England, nowhere in the United States is the Franco-American presence stronger than in the Pine Tree State. Living in Maine, especially in a place like Brunswick, requires some awareness of this unique heritage and culture that has persisted despite repeated attempts at forced assimilation.

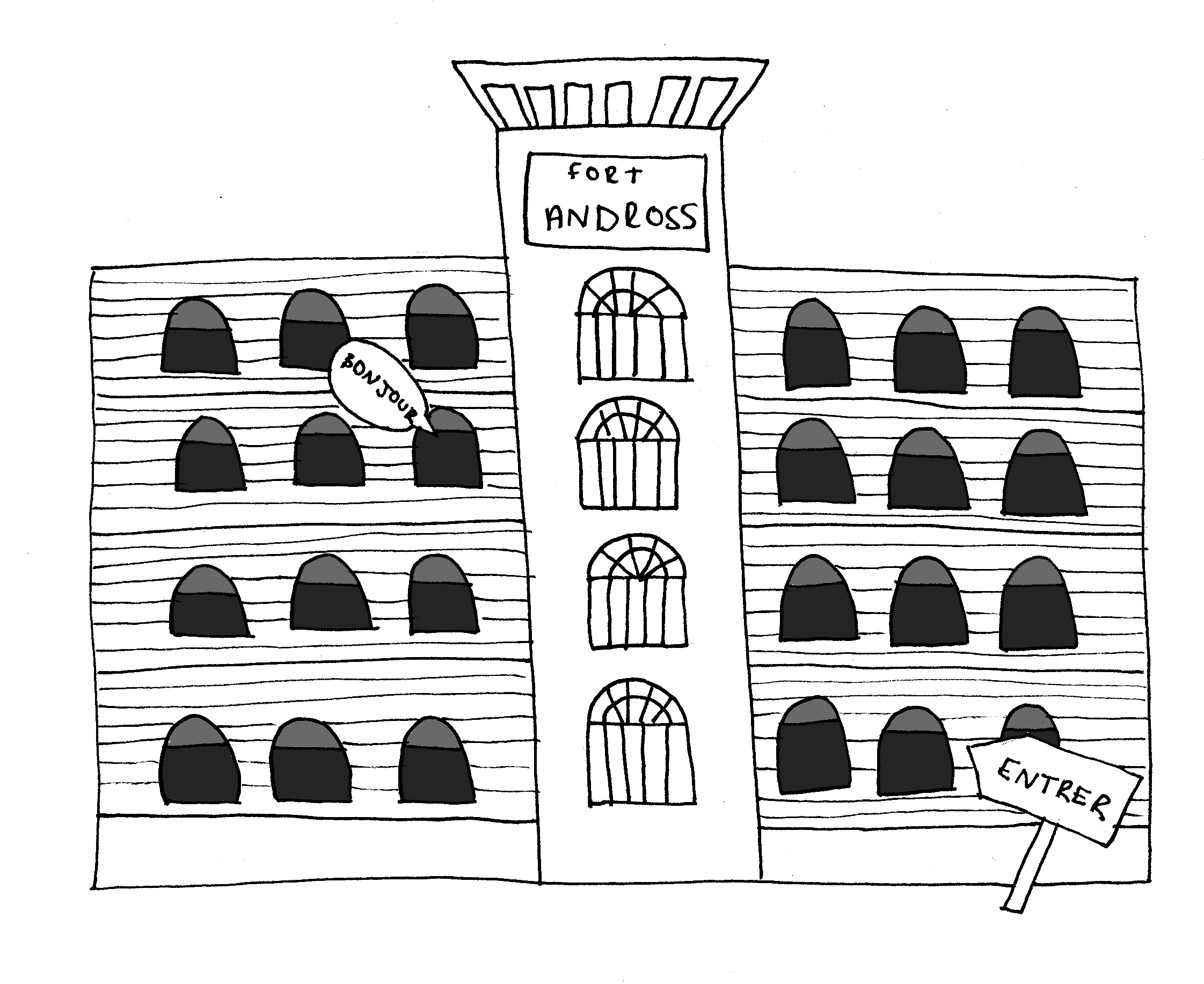

Franco-Americans in Maine can largely be divided into two groups: the St. John River Valley Acadians, who settled in the North after the British expelled them from the Canadian Maritimes, and French Canadians, who came from Québec in the 19th century seeking better employment prospects. Though their identities were slightly different, both groups brought their language and Catholic religion to their new homes. Most immigrants from Québec settled in mill towns in Central and Southern Maine, such as Lewiston, Biddeford, Waterville, Augusta and Brunswick. Many were employed in textile mills, such as the former Cabot Mill (now Fort Andross) in downtown Brunswick, and communities known as “Little Canadas” formed around the mills. These neighborhoods often had their own churches and parochial schools, which taught the French language and Catholic beliefs to the children of French-Canadian immigrants. As a result of their community bonds, French-Canadians tended to assimilate more slowly than other ethnic groups in the state. Acadian settlers, centered around towns on the St. John River like Fort Kent, Madawaska and Van Buren, also resisted Anglo incursions. Most had roots in the area predating the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842, which drew up the current border between Maine and Canada, and cross-border ties were common. Agriculture was more important to them, although some did move south in search of employment in the mills.

Because of their different language and faith, Franco-Americans were often the target of slurs and other forms of discrimination. Students speaking French in Maine’s schools were beaten and ridiculed, and even their French teachers disparaged their “impure” regional dialects. In mill towns like Lewiston, riots often broke out between Franco-Americans and Irish-Americans, who perceived the newcomers as a threat. Yet, Franco-Americans persisted. From modest backgrounds of mill labor, many became entrepreneurs or worked their way up in local and state offices. Paul LePage, Maine’s current governor, grew up speaking French in Lewiston, and despite an abusive home life, managed to work his way through college and into politics. Countless others have had considerable impacts on their communities.

Today, Franco-Americans are still an important part of Maine’s cultural fabric, and, though their culture is no longer as distinct as it once was, there are numerous efforts to preserve their heritage. Community groups in Lewiston meet to speak French, parents send their children to L’École Française du Maine and researchers at the University of Maine’s Franco-American Centre examine their complex history. There are even a few churches that still give Mass in French. Elsewhere, reminders of the importance of Franco-Americans abound. Look around Brunswick, for example, and you will see quite a few streets and landmarks adorned with French names, from Baribeau Drive to the Tondreau building downtown. Their influence is even visible at Bowdoin: look no further than the Pinette Room in Thorne Hall, named in honor of former Bowdoin employee Laurent Pinette.

I have always been fascinated by Franco-American culture and language. My first French teacher was an Acadian from Fort Kent. I grew up eating ployes (Acadian buckwheat pancakes) and listening to Acadian and Québécois folk music. One of my favorite things about this state is this unique dimension of its heritage, and I hope that you too can learn to appreciate it. Ask your Maine friends here about their family history, go visit Fort Andross and keep an ear out when you’re out on the town or if you somehow find yourself in Sabattus. You might just catch a hint of a French accent—and the beginning of a really interesting story.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

I ran into Franco-Americans in my French class when I was student teaching in Skowhegan. What the students spoke at home every day wasn’t exactly what I had learned in Brittany and Normandy. They put up with my Gallic accent in class and we all learned a lot. It appears that more than 3% of Mainers speak French at home.

I speak Mainland Canadian English and Newfoundland English. There’s nothing wrong with speaking two versions of the same language. It’s too bad these francophones aren’t encouraged to keep their French up and expand it through public French language schooling. I hope you didn’t ridicule them for their regionalisms and learned something from them. I always like the way educated Franco-Ontarians can switch from a regional French which I don’t understand to a more standard version of French which I do understand. Of course, we have French schools and Early French Immersion schools in Ontario: to preserve the language.