Challenging confines of the frame with Sascha Braunig

November 2, 2018

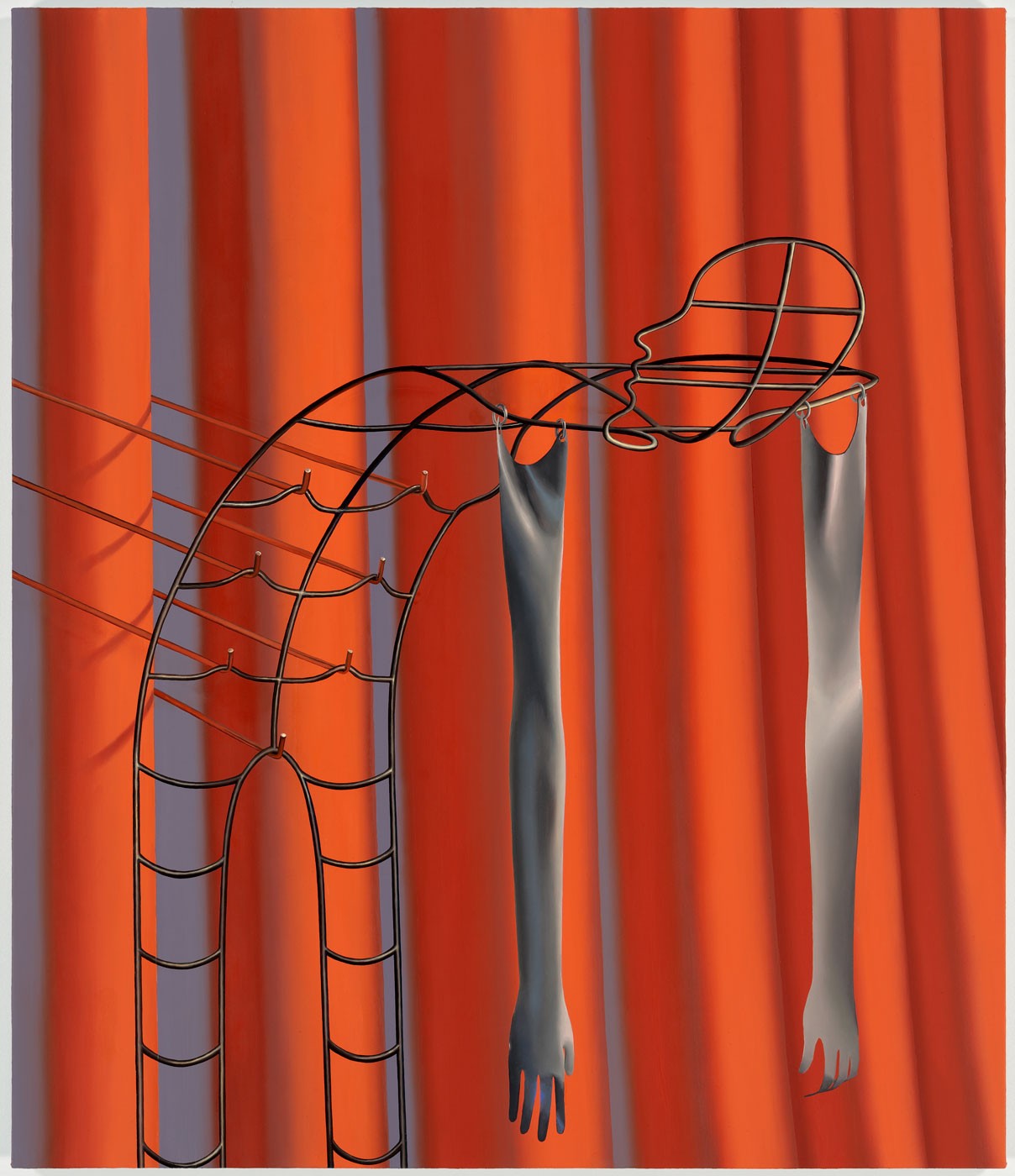

Courtesy of Sascha Braunig

Courtesy of Sascha BraunigCoiling forms, spatial fantasies and abstracted bodies—boundaries between the real and the imagined become indistinguishable in the vibrant canvases and eerie motifs of Sascha Braunig’s work. Originally from Canada, the Portland-based artist came to Edwards Center for Art and Dance on Tuesday afternoon, decoding her pictorial puzzles through a glimpse into her creative evolution.

Renowned for her unique interpretation of modern sentiments, Braunig’s work has been highlighted by esteemed institutions, including solo shows at the Museum of Modern Art PS1, Foxy Production in New York and galleries in Norway, Belgium and Switzerland. Braunig, however, traces the start of her career to a crudely painted mask made back in her youth.

“I was really struck by the fact that I’m essentially making the same work as I was at 12,” said Braunig. “[This piece] encapsulates ideas about psychological masking and the construction of the self—especially the feminine or femme self through ornament and fashion, facial distortion and vibrant, bright colors.”

At first glance, Braunig’s paintings are disturbingly arresting; contorted silhouettes emerge out of twisted wires, stretched metal or sculpted clay. This interplay of opposing color, texture and light stems from early influences by Dutch trompe-l’oeil still lifes, commercial photography and even pop-culture references such as “The Terminator.”

“[In commercial photography], the feminized body becomes one luxury material amongst others,” said Braunig. “And I was painting from photographs like this … this constant association of the body with inanimate objects, which [the figure] brings into a commercial setting.”

After finishing her studies in painting and photography at The Cooper Union, Braunig went on to pursue her graduate degree at Yale, a time during which she frequently worked in video. As she slowly transitioned back to painting, she sculpted molds of the human figure to play with patterns and distortions. Crafted in simple materials such as clay, paper or styrofoam, materiality and tactility served as a creative outlet.

“The idea that this dummy thing was my muse really freed me to extrapolate and have fun with color and texture. I was making these things sort of in the dark as well, really identifying with a object,” she said.

In a neo-Surrealist way, a viewer can barely look at Braunig’s paintings without wondering what is exactly being depicted. Indeed, her paintings are marked by a striking polarity: the photorealistic rendering is juxtaposed with totally disembodied, Kafkaesque subject matter.

Yet different from Surrealism’s focus on the subconscious mind, Braunig’s work is often responding to tangible impulses, tapping into anxieties and instabilities rooted in reality—her featureless figures are animated with action, agency and assertiveness.

“Around the time of the 2016 election, which I couldn’t help but be affected by in my work,” she said. “That’s where this like flopping backwards gesture [in the painting] comes from … as kind of like a irrational gesture of exasperation, a throwing up of hands, although there are no hands here, and perhaps even a kind of surrender against structures.”

Braunig is at the same time highly conscious of art historical precedents, reclaiming historical symbolism in the context of a renewed, feminist vocabulary. One prominent example is her depiction of the witch, evermore powerful against the backdrop of the #MeToo movement.

“[Historically, the witch] obviously represents some pretty ugly ideas about fear of the elderly and fear of women … definitely tied up with the history of witch hunts. Dürer and other artists used her as a way to present an image diametrically opposed to a feminine ideal,” she said.

She paints witches as flattened silhouettes with multiple legs that resemble Hindu deities, thrusting into the viewer’s space. To Braunig, these figures are sexy and powerful.

“I’m kind of embracing and reclaiming the word witch as an epithet … I just have felt the urge to invite feminism more explicitly into the work rather than sort of touching on it, through these art historical narratives,” she said.

Though amorphic in representation, the figures of Braunig’s work have minds of their own, embodying the vulnerability as well as strength of the modern woman.

“The figure [in my paintings] grapples with the frame [as] kind of an entity acknowledging the conditions of her confinement, which is the painting’s edge—so they’re kind of actively struggling with their own representation rather than frozen inside of it.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: