‘Geel:’ interactive performance opens mind and body

September 28, 2018

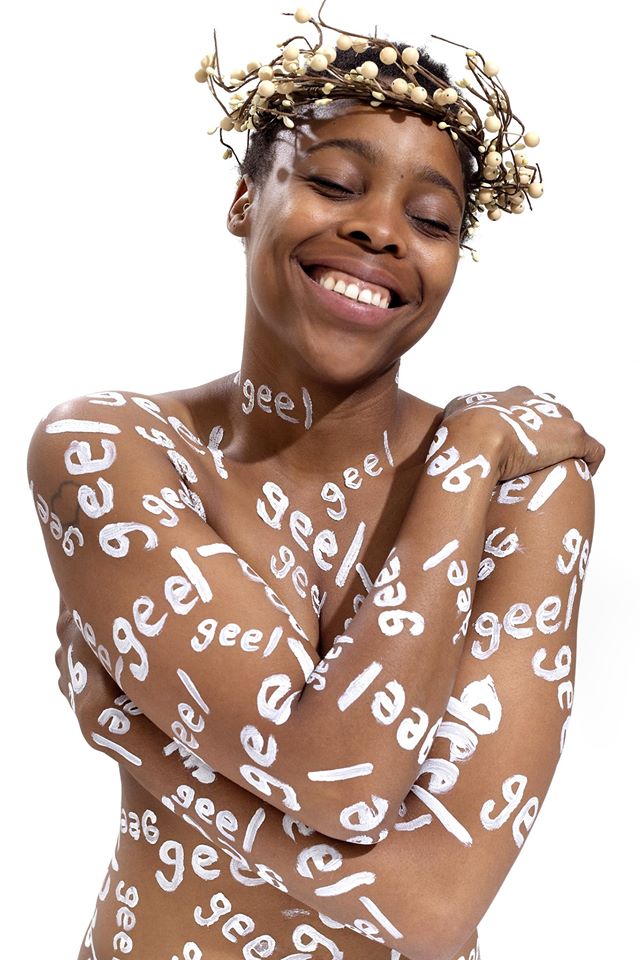

Courtesy of Sara Barlow

Courtesy of Sara BarlowThe lights go down, and the whole room is black. Walls, floor, ceiling—everything black. A figure, dressed (you guessed it) in black, emerges from the right, singing in Afrikaans. After nearly 90 minutes of intense interaction and emotional performance, the theater will return to this: everything black. One thing, however, will have changed dramatically from the start—the audience.

Watching René Goddess Johnson’s energetic, powerful and interactive one-woman show “geel” is a full body experience. Johnson asks more of the audience than just their presence, she asks them not to dissociate, but to actively engage.

“My show began because I was just trying to hear my own voice and listen to my own story,” Johnson said. “I come from severe abuse and trauma. I was diagnosed with PTSD when I was 12, and this story kind of evolved into something around the same time I realized that art was a language I never had access to for myself.”

Born in South Africa, Johnson moved to Portland, Maine at age six. She and her twin brother lived with their birth mother, her significant other and their child in the suburbs. Soon after they arrived, Johnson’s birth mother began to severely abuse her children, both physically and emotionally.

Johnson quickly developed self-harm mechanisms and suicidal thoughts. Never understanding why she received the brunt of the abuse, she felt isolated. Ballet became one of her most frequent methods of self harm, a way to intensify her pain.

The audience, however, knows none of this until the second half of Johnson’s show. The first half of “geel” is interactive and upbeat. All the exercises employ tools Johnson used as coping mechanisms during the abuse she received throughout her life.

Johnson opens her show by portraying her grandmother. She teaches the audience a song line by line and asks them to engage by stomping, dancing and singing along. The audience is asked to hold eye contact for 45 seconds while talking, then again for a full minute in silence. Such a task should be simple, Johnson explains, but in America it is far from easy.

“I’m just asking you to look a person in the eyes,” Johnson said. ”If you are feeling shame or doubt or fear, I want you to really think about that.”

The second half of the show tells Johnson’s story through age 13. It opens with a chilling retelling of her first encounter with abuse. Through dance, words, screaming and violent movements, Johnson acts out her mother choking her twin brother, laughing and hurling him down the stairs.

“We were just in awe that someone could survive this and still walk, and smile no less,” said Davis Robinson, professor of theater and producer of “geel.”

Johnson’s self-proclaimed reinvention of herself fuels her desire to share. Because she suppressed so much emotion as a child, Johnson feels she never had sufficient time to work through her trauma and emotions.

“A big portion of why I keep doing this show is because it brings up so much of what my child-self suppressed. I’m learning only now at 34 that I don’t know who I am,” Johnson said in an interiew with the Orient. “I don’t actually know who I am.”

The show is vital to her continued exploration of what it means to be an “embodied equity consultant.” Having reinvented herself in this image, Johnson aims to fully—spiritually, physically, mentally—think “top to bottom” and treat herself and others in the most fair way possible.

“Everyone has their story, and I think everyone’s story is difficult,” she said.

Johnson opens a complex dialogue about American culture. Throughout the show, she contrasts her experiences in South Africa with those of her time in the United States. Describing America as a “corporation,” she uses her perspective as a woman of color from a different country to evaluate American society and suggest changes she sees as imperative to the development of the state.

“It’s important for shows like mine to exist on campuses like this, where people are in a space of believing that they are inclusive, believing that they are being diversely intuned, believing that they are working in the right direction toward gaining equality for social justice and social equity and for minorities,” Johnson said. “People need to hear a message of ‘Oh wait, are we what we say we are? Are we doing what we say we do?’”

Following the show, Johnson spent time talking to students, listening to their reactions and recovering from the immense emotional distress that envelops her during the show. For her, this is one of the most meaningful parts.

“People of color were so grateful to see someone that looked like them on the stage here,” Johnson said. “And that always breaks my heart because again, you can’t tell me you’re an inclusive space if the only people being presented for the most part are white.”

For Robinson, bringing “geel” to Bowdoin is part of a conscious effort to increase representation of people of color on campus and create dialogue about race. But Robinson noted that the performance is not only beneficial for acting students, but also for the general audience.

“I hope it shows that you can take really powerful, really personal material and put it to good use and own it in a way that turns it into a work of art that you can share with people,” Robinson said.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: