Administrative hires exceed those of faculty as needs change

October 13, 2017

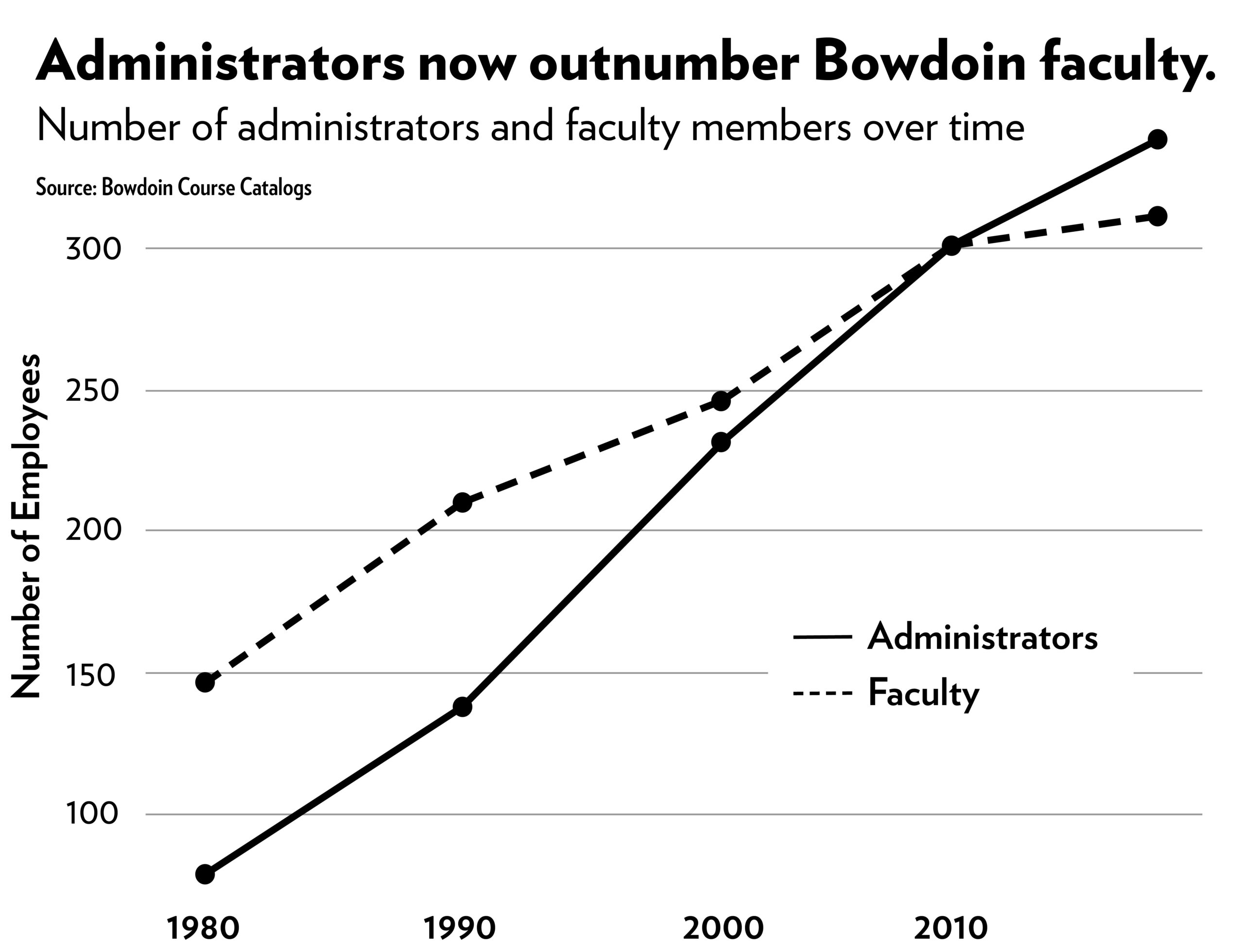

When Bowdoin first opened its doors on September 3, 1802, it had two employees: President Joseph McKeen and one professor, John Abbot. Together, they taught eight students. Since then, the College has grown to staff over 945 employees with 1,806 students. But in 2010, Bowdoin reached a new milestone that would affect the distribution of responsibility of administrators and faculty on campus. For the first time in its history, the College began employing more administrators than instructors.

An Orient investigation into college hiring decisions reveals that since 1980, Bowdoin prioritized administrative hiring over instructor hiring as it added hundreds of positions in offices ranging from Dean of Students to Development and Alumni Relations.

As a result, while the instructor to student ratio has gone from about 1:9 to 1:6 since 1980, the administrator to student ratio has jumped from 1:17 to 1:5 during the same time period.

This shift in hiring prioritization is consistent with peer institutions, according to Charles Dorn, professor of education, associate dean for academic affairs and associate affirmative action officer.

“It is absolutely the case that, over the course of the past few decades, what you might call administrative bureaucracy at many institutions really has mushroomed. So there’s been a dramatic increase—a disproportionate increase—in the number of administrators compared to faculty,” said Dorn, adding that he does not believe this is the case with respect to the Office of Academic Affairs at Bowdoin and that he believes Bowdoin’s growth has been limited compared to some bigger public universities.

Gideon Moore

Gideon MooreMost recently, in August, the College announced the creation of a new administrative position—a Senior Vice President for Inclusion and Diversity. President Clayton Rose made the announcement at the recommendation of last year’s Ad Hoc Committee on Inclusion.

As defined by the classifications in the academic handbook and the college catalogues, the College currently employs 333 administrators and 318 instructors according to the online academic handbook. The Orient found 9 employees who are listed as both administrators and instructors.

Administrators range from deans to software engineers, and some hold multiple positions. Instructors’ positions include tenured faculty, assistant professors, lecturers, language teaching fellows, laboratory instructors and even sports coaches. Examples of individuals who hold positions in both categories are Dorn or Associate Director of Athletics Lynne Ruddy, who is also an assistant coach of the track and field team.

Professor of Latin and Greek Barbara Boyd explained that the role of the faculty on campus has narrowed since she arrived at the College in 1980.

“It used to be that faculty played really decisive roles in some things besides the curriculum. That’s no longer the case,” said Boyd.

For example, in the 1980s, Boyd served on the admissions committee along with two or three other faculty members, spending a week over break reviewing applications and helping make the final cuts before acceptance letters were sent out. Since 1980, admissions has professionalized, growing from six administrators to 14.

“Something is missing now that we’re not there. We may not have all the abilities that those folks have, but they’re missing some of the abilities that we have and that’s unfortunate,” she said.

Boyd noted that faculty meetings also changed significantly over the past few decades, particularly during President Robert Edwards’ term from 1990 to 2001.

“In some ways it’s more like the managers reporting to the employees and less like colleagues,” said Boyd, referring to the way she believes faculty meetings are now run.

Dorn straddles the world between administrator and instructor. His role as associate dean for academic affairs is a three-year, full-time position held by a professor chosen by the faculty.

“I don’t feel the tension in myself between being faculty member and an administrator,” said Dorn. “My role in this office is to collaborate with faculty and colleagues and with departments and programs to provide them with the best educational experience we can for students.”

In addition to communicating with departments, Academic Affairs continually tracks enrollment numbers to see if more instructors or tenure-track positions are needed.

“We’re able to track increases in enrollment over time and if we find—as was the situation in computer science last year and mathematics last year—that there’s a sort of spike in enrollment and a continuing spike,” said Dorn.

As such, this tracking done by academic affairs is one of the ways faculty positions are added.

Another area of expansion at Bowdoin is at the Hawthorne-Longfellow Library. In 1980, it employed just eight administrators whose positions ranged from acquisitions librarian to cataloguer. Today, it employs 35 administrators who hold positions ranging from academic multimedia producer & consultant to associate librarian for discovery, digitization and special collections and director of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives.

Professor of Government and Legal Studies Allen Springer has taught at the College since 1976. Soon after arriving at Bowdoin, he served as the dean of students while still serving as a professor, but the role of the office has expanded since he started at Bowdoin.

“Dean of students then was a very different position. The College was differently structured and the dean of students actually reported to the dean of the college. My office didn’t have nearly the range of responsibilities that [current Dean of Student Affairs] Tim Foster has,” said Springer.

“I think there’s just a recognition now that a lot of different administrative areas that in the past were covered more thinly can profit by having more people working in them,” he said.

In particular, Springer noted how the growth in administrative roles has redirected responsibilities once held by Counseling Services and individual advisors into more competent hands.

“I think we’ve recognized the need to deal with issues like sexual harassment and other things in a more pragmatic way than we tried to back in the late 1970s and 80s,” said Springer. “Part of the reason was we didn’t have the people at the time and, in some cases, the expertise to do that.”

One of the new positions added since the 1980s is Benje Douglas’ position as director of gender violence prevention and education as well as Title IX coordinator. In these capacities, he works to prevent and respond to violence on campus.

“Colleges have changed a lot in 35 to 40 years. Both the consistent needs of students coming in and the expectation that we have consistent professionals who can deliver on those needs I think is very important,” Douglas said.

Douglas also noted how the line between administrator and instructor is not always clear in a liberal arts setting since learning happens both inside and outside the classroom.

“I do think that everyone I work with as an administrator is an educator—we’re just not faculty,” said Douglas. “Faculty have a really specific, important and unique role for the education of students here that is wildly different than what we do, but I think that what we do can be complementary of it in the fact that we’re showing in action some of the things that are discussed in the classroom.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that employees were listed as either administrators or instructors and those who held concurrent roles were only listed as instructors; 9 such employees are in fact listed as both, although 3 are only listed as instructors. Additionally, a quote from Charles Dorn lacked context to fully explain his position; clarifying context has been added.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: