Growing connections: Professor Hadley Horch discusses neuronal growth research in inaugural lecture as endowed professor

March 28, 2025

Abigail Hebert

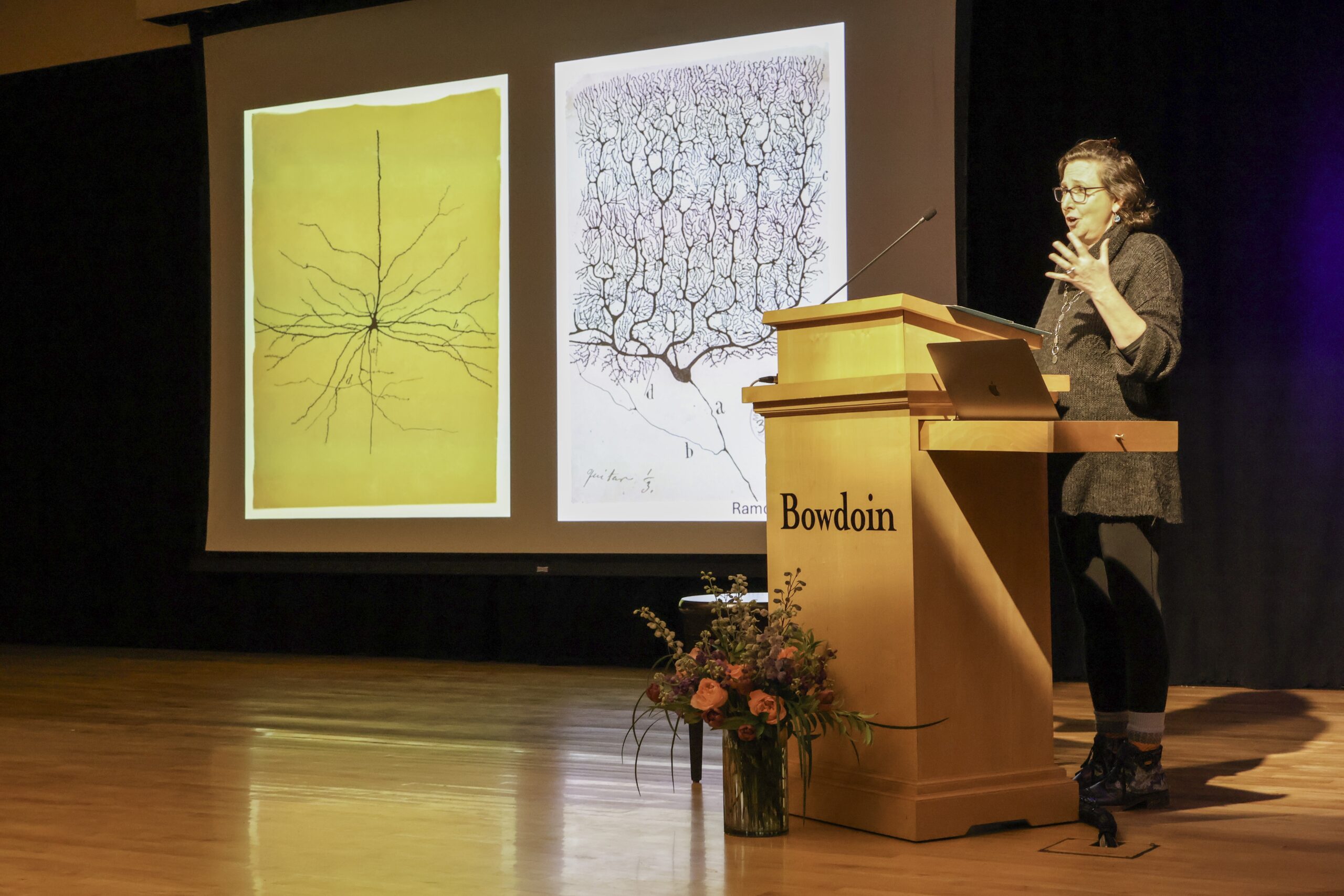

Abigail HebertOn Wednesday night, Professor of Biology and Neuroscience Hadley Horch took the stage in Kresge Auditorium to deliver her inaugural lecture as the endowed Norma L. and Roland G. Ware Jr. Professor. In the lecture, “Branching Out: The Molecular Gardeners of Dendritic Arbors,” Horch talked about her decades of researching neurotrophins, using Mediterranean crickets as a model organism.

Horch began with the history of her field, including the story of Rita Levi-Montalcini, an Italian neurobiologist. Levi-Montalcini worked in a makeshift lab she created in her childhood bedroom while her home of Turin, Italy, experienced repeated bombings during the First World War. She later won the Nobel Prize for her discovery of neurotrophins—the subject of Horch’s research.

“I find [this story] really inspirational, and for me, it highlights the resilience and curiosity inherent in the human spirit,” Horch said.

Horch then spoke on her research, which began at Duke University and focuses on neurotrophins, which influence neuronal growth, survival and axonal growth. The goal of her research is to discover if neurotrophins influence the growth of dendrites, the part of the neuron that receives action potentials. Horch believes that her research can advance the collective understanding of mood disorders and how the nervous system recovers from injury.

“Neurotrophins are very involved in mood disorders. So we think that [brain-derived neurotrophic factor] levels are really low in people who have depression, especially depression that’s hard to treat.… And we also know that it plays a role in injury,” Horch said.

Arriving at Bowdoin, Horch let go of the vertebrate model organism she had previously worked with and adopted an invertebrate model: the Mediterranean cricket. The Mediterranean cricket is a particularly interesting model organism to Horch because of the compensatory plasticity of their nervous system. Crickets have their tyrannic membranes—their ears—on their forelegs, which send signals via auditory neurons to the central nervous system, meaning a lost leg deafens them on that side.

“[Upon losing a leg, the auditory neuron] could die, it could hang out, it could do a number of things, but what this cell does is it sprouts across the midline, the center of the body. Neurons usually respect that, but this one spreads across, and it actually grows right toward the axons coming from the opposite side, and it gets functionally connected to the axons from the opposite ear,” Horch said.

Horch’s current research focuses on Spätzle, a neurotrophin proven to be important for cell survival and axon outgrowth in fruit flies. Her lab is currently exploring the role of its ligand, or receptor, Toll-6, on neuronal branching in Mediterranean crickets.

“So if we take an intact animal, we can experimentally decrease the level of Spätzle or [Toll-6].… The prediction from this is that these animals are going to have an altered ability to respond to sound,” Horch said. “We [also] think that the dendritic morphology is going to be altered compared to normal. And if we were actually to test the behavioral responses, its ability to respond to sound, those would be different as well.”

Federica Lombardi ’27 attended the lecture and enjoyed the historical background Horch shared.

“It was extremely interesting,” Lombardi said. “One thing I think about every time I hear [Horch] talk about her research is how we could learn and then take this to other animals and humans.”

Professor of Biology Jack Bateman also attended the talk.

“Hadley is a good friend. She’s a colleague of mine, and I am excited by the research that she does. So I wanted to come learn about her lab’s recent work and to support her in this amazing achievement,” Bateman said. “Biology is amazing.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: