Dr. Vanessa Northington Gamble talks leadership, health inequity and the life of Dr. Virginia Alexander

February 9, 2024

Rie Du

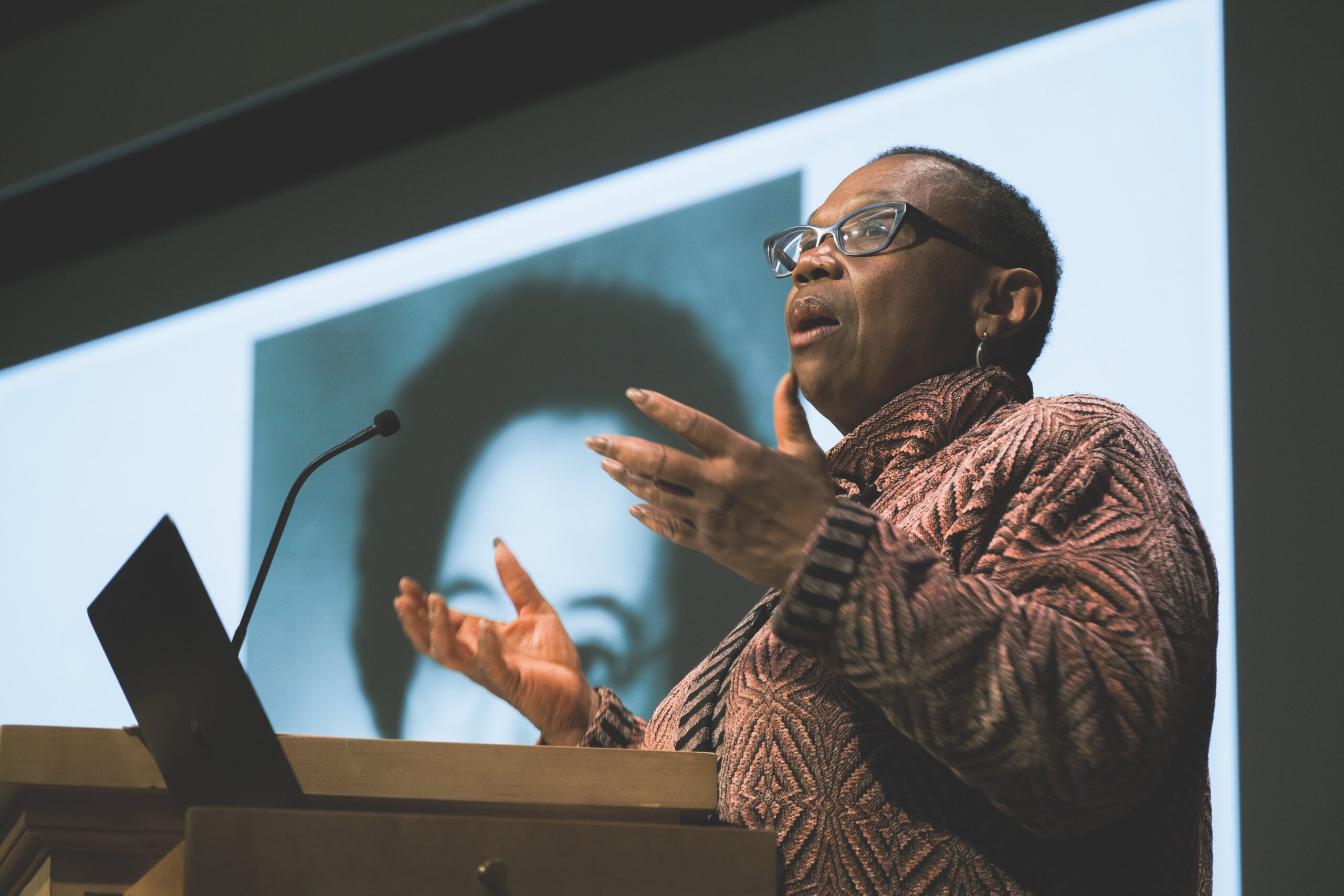

Rie DuPhysician, scholar and activist Dr. Vanessa Northington Gamble visited Bowdoin on Tuesday to discuss health inequality for Black Americans, her work as a pioneer in the medical field, health inequality for Black Americans and the life of one of her professional foremothers, Dr. Virginia M. Alexander.

As this year’s Arnold D. Kates lecturer, Gamble presented her talk entitled, “Striving for the Health of Black People: The Life and Medical Career of Dr. Virginia M. Alexander,” in Kresge Auditorium. Alexander, an African American physician who lived from 1899–1949, is the subject of the biography Gamble is currently writing.

“I have dedicated a large part of my life to uncovering the lives of African-American physicians, women physicians especially, whose lives have gone unrecognized,” Gamble said at the lecture. “[Alexander] believed that the health of Black people was worth striving for.”

Gamble began her talk by giving attendees a brief history of Black female physicians. She showed pictures of Black physicians who were the first in their fields and faced intense struggle while breaking down barriers.

“Dr. Alexander was not the first Black woman pioneer in medicine,” Gamble said. “Black women have been a part of medicine since the nineteenth century.”

Gamble spoke vividly of the discrimination Black physicians faced, including rejections from universities due to their race, segregated hospitals that would not allow Black physicians to treat white patients and consistent mistreatment from patients and colleagues.

Gamble’s talk focused on the burden pioneers often take upon themselves while breaking down barriers.

“A friend cautioned [Alexander] at the beginning of her career, ‘You are a pioneer, and their lot is never easy,’” Gamble said.

Alexander’s struggle as a trailblazer in the medical field is far too familiar for Gamble. She is the first woman and first African American to hold her endowed faculty position at George Washington University. In addition to serving on dozens of other boards and committees, she chaired the committee that led a public campaign to obtain an apology from the United States government for the untreated syphilis study at Tuskegee, where doctors withheld life-saving medication from over 400 African American men with syphilis.

“The thing that sometimes happens with being a pioneer is that, if you fall off the path, you don’t know how to get back on it. No one or no one in your family has done it.… But there’s also a deep sense of pride,” Gamble said. “The goal of someone who has been the first is to be in the position where there are people who are following behind you…. I will not have done my job if I’m the only one. My job is to make sure that people come behind me.”

The Office of Stewardship wanted to bring Gamble to campus because of her trailblazing work in the public health sector.

“[Dr. Gamble’s] background as a groundbreaking physician, scholar and activist, as well as her influential work to identify and combat racism in the health and medical fields … made her a terrific fit as the 2024 Arnold D. Kates lecturer,” Associate Director of Stewardship Christine Sullivan wrote in an email to the Orient.

Gamble began the research for her biography by gathering information from Alexander’s papers, her friends’ diaries and letters, and Black-owned newspapers.

Originally from South Philadelphia, Pa., Alexander worked multiple jobs to support herself and attended the University of Pennsylvania for undergraduate training, where she found a community of Black women passionate about making change.

Alexander began medical school in 1920 at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, where she was the only Black woman in her class. She faced discrimination, surrounded by racist classmates and professors who believed she did not belong there. Alexander’s political activism started in medical school, where she led her classmates in several protests against the administration.

Returning to Philadelphia after completing her internship in Chicago, Alexander was determined to improve healthcare for African Americans. She opened a three-bedroom hospital in her own home, where she was committed to providing Black patients with quality care they could not receive elsewhere.

“As Virginia’s practice expanded, she started getting interested in the social and political aspects of medicine. She called her practice a ‘socialized practice.’ For her, that meant service to the community was the center of the practice. It was a sanctuary and an antidote to the racism in Philadelphia,” Gamble said.

Alexander grew her interracial practice, treated over 2,000 patients, often without payment, and was a spokeswoman for equality in the public health sector.

“[Dr. Gamble] spoke about shifting the narrative to highlight what physicians such as Dr. Virginia Alexander have accomplished instead of focusing on what they have not or could not,” attendee Sarah Conant ’24 said. “I found it valuable to hear her perspective on racial and ethnic health disparities through the lens of her studies on Dr. Alexander.”

Gamble was careful to paint Alexander as a fully fleshed-out woman. She struggled with her mental health in the face of intense scrutiny, yet was able to find faith and solace in her religion as a devout Quaker. She died from lupus at age 50.

“[Alexander was] a passionate advocate for health equity, long before it reached prominence as a national public health initiative,” Gamble said.

Gamble reflected on how her research into Alexander’s life has shaped her as a physician and activist.

“The thing I have learned the most [from Alexander] is to keep going. Life has ups and downs, but when you think you’re doing something important, you do it,” Gamble said. “I am on the shoulders of these Black women…. Virginia is truly dead if I stop doing what I do in terms of talking about health equity and rallying people to continue to talk about it.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: