Frustration over pay and fairness rising among College workers in dining, housekeeping

November 3, 2023

Bowdoin workers are grappling with long-standing economic challenges in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, with widespread complaints that the College is not doing enough to pay people fairly or address the rising cost of living in Brunswick.

A convergence of trends in the post-pandemic economy is hitting Bowdoin and peer institutions hard as they try to recruit and retain a labor force, counter high turnover and maintain morale, especially among veteran employees.

In several interviews, housekeepers and Dining employees said their frustration is mounting.

College administrators acknowledged that Covid-19 changed the labor market in ways that have affected Bowdoin. Last summer, the College hired New York-based human resources consulting group Segal to study Bowdoin as an employer in comparison to peer institutions and other employers in the market. The College does not plan to publish the results of the study, Senior Vice President for Finance and Administration & Treasurer Matthew Orlando wrote in an email.

“That data is too sensitive,” Orlando wrote. “Some of our departments are very small, so even the aggregated data would be too revealing.”

Nikki Harris

Nikki Harris“A morale issue”: Similar pay between old and new employees

One challenge facing some college employees is a phenomenon called “wage compression,” in which rising starting wages cause new employees to earn nearly as much as employees who have worked at the College for years.

Trio Crossman, a Dining aide in Moulton Union, has been at Bowdoin for around ten years. It bothers him to see newer employees at the College earning a wage close to his.

“When the College went from $17 to $17.50 [in its starting wage], a lot of us were a little upset because somebody could walk off the street with no experience, making 35, 40 cents less than somebody like me, who’s already been here ten years,” Crossman said.

An employee at the College, who asked to keep their name and department anonymous to avoid reprisal from their managers, shared similar concerns.

“I’m someone who has been here for [over a decade] and I make roughly two dollars more an hour than the person off the street doing my same job,” they said. “And if they’re gonna raise the starting rate, they need to raise the rate of the people that have been [here] a long time.”

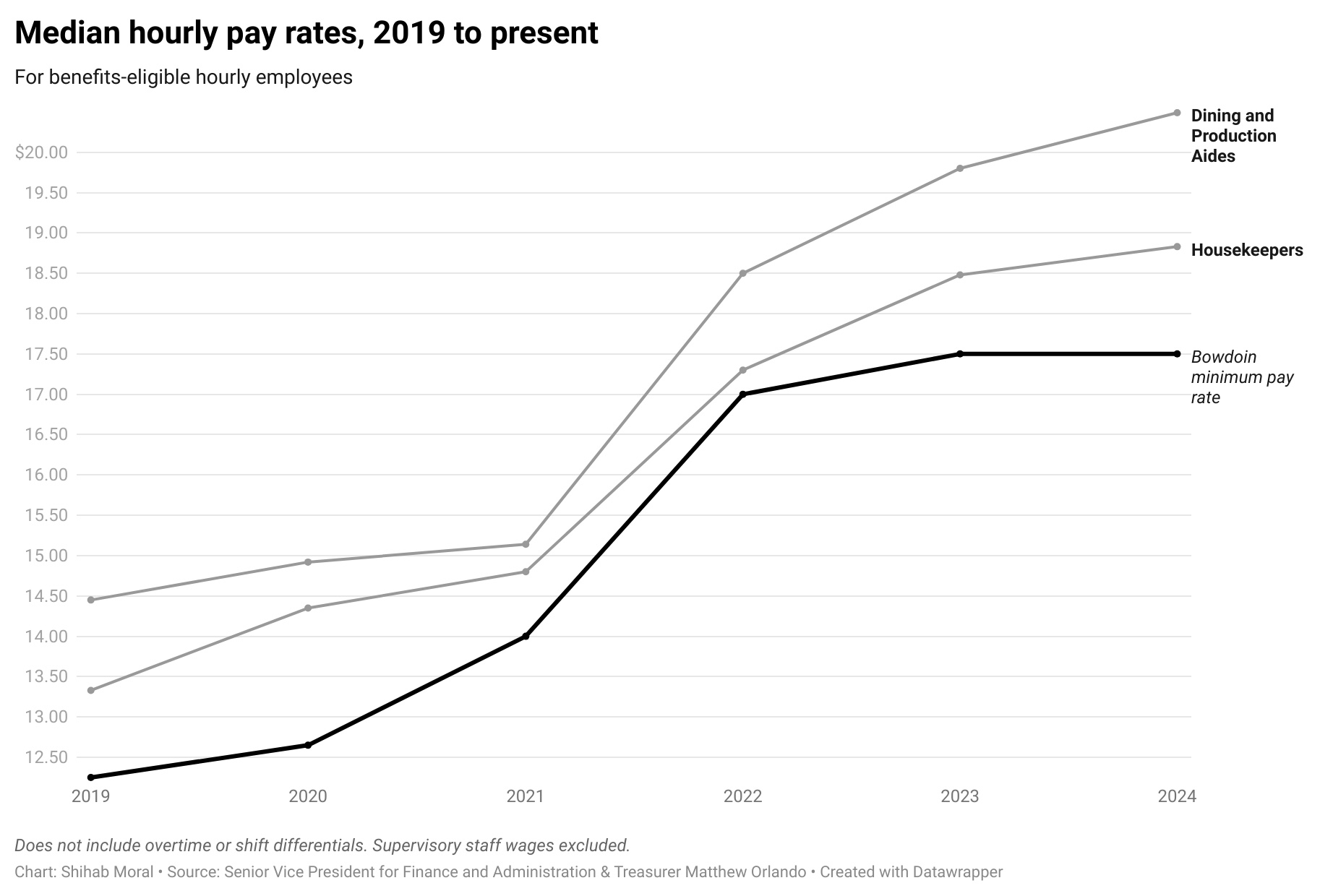

Data provided by Orlando illuminates the issue. The College has raised its starting wage by over five dollars since 2019 to keep up with inflation and fulfill the commitment it made in 2019 to have a $17 per hour starting wage by 2022. The starting wage is now $17.50 for benefits-eligible hourly employees, up $5.25 from the $12.25 starting wage in 2019.

According to the MIT Living Wage Calculator, the living wage for one adult with zero children in Maine is $16.53 per hour—roughly one dollar less than the College’s current minimum wage.

Orlando said the data also is evidence of the College’s efforts to relieve wage compression.

“You can see that in 2023 & 2024, we relieved much of the compression that was created when we moved rapidly to $17/hour in Aug 2021 ([for year] 2022),” he wrote in an email to the Orient.

In an interview with the Orient, Orlando said that one of the takeaways from the Segal study is to further reduce wage compression.

“Wage compression is a morale issue,” Orlando said. “If you’ve been working for the College for a long time, and we’re getting your annual increases that might have been 50 cents, and then we moved the minimum wage up to levels that took you years to get to, you want to make sure you take care of those folks so you move them in step function, to some degree.”

Orlando said that time spent at Bowdoin is one of many factors in determining fair pay for employees.

“It’s just not about years in the job, that certainly matters [and] experience matters, but so does performance, so does the effort and quality of the work,” he said. “So all of those things factor in.”

Employees frustrated by a lack of recognition

Another concern employees raised is that low-performing employees receive pay raises and performance evaluations similar to those of high-performing employees. The College’s performance evaluations, some employees say, are insufficiently critical of employees who put in low effort and not rewarding enough of those who do the best work.

The quarterly performance evaluation system, instituted last year in replacement of an old annual evaluation system, evaluates employees on a scale of one to five.

“There’s people that come in who do the minimum … and are not putting much effort in, and they’re getting the [rewards] when there’s other people that come in every day that usually never call out or ask for time off. And they’re staying late and not being noticed,” Crossman said. “It’s not fair that someone who deserves a one [out of five on their performance evaluation] is still getting a little bit of a raise.”

Todd Bullis, a meat cutter in Thorne Hall, says that pay raises in Dining Services do not differ enough by employee.

“As far as how evaluations and raises come about, it’s all as one. They don’t look at you as an individual and your individual efforts and your personal growth,” Bullis said. “It’s more looked at as a whole. And it’s, ‘OK, now everyone’s getting a pay raise.’… You’re not getting a pay raise [based] on what you did, so you don’t even really feel good about it. You’re like, ‘OK, great, do you really appreciate me or is this just something you’re obligated to do?’”

Orlando said that managers in the past have been reluctant to give harsh evaluations to low-performing employees. In the future, the College plans to train managers to give more honest evaluations.

“I would say we could do a better job across campus in this area…. Managers have historically tended to shy away from the tougher conversations with the poor performers, not that we have a lot of them,” Orlando said. “I would say [wage increases] cluster too closely around the mean.”

“I do believe that notable differentiation between high performers and low performers should be reflected in how wage increases are allocated. And this is certainly something we plan to emphasize and monitor more carefully going forward,” Orlando said.

Another factor the College uses to calculate wages is market rates, according to Orlando.

“We pay at the top of the competitive market…. The market is our guidepost. We haven’t ever indexed wages specifically to the cost of living, and actually if you’d done that in the last 10 or 20 years it would not have been to the employees’ benefit,” Orlando said.

According to some employees, though, this competitive market rate is not yet enough.

Bullis said that he has considered moving out of Brunswick because his family is struggling to afford housing with his current pay rate.

“A lot of financial situations that my wife and I deal with are whether we are going to be able to continue living in Brunswick. Then, OK, let’s take a look at the housing market. There is no housing market, it’s gone. Covid[-19] came and wiped it out,” Bullis said. “So you don’t want to live out of the community that you live in. You don’t want to be on the outskirts and coming to work from 30 miles away, because that’s what it feels like is starting to happen.”

Concerns not universal among employees

Other employees’ experiences at Bowdoin, however, are largely positive. Derik Shean, a Dining employee in Moulton Union, said that Bowdoin is more diligent in paying employees for working overtime than one of Shean’s previous employers.

“I worked for a small business many years ago. They didn’t pay overtime. What they did was carry whatever you had for overtime for the following week or for the week that you didn’t get a full 40 hours,” Shean said. “But here at Bowdoin they have no problem paying overtime and in fact encourage you to stay and finish the job.”

Jenn Mocarski, a recently hired electrician at the College, has similarly positive feelings about her experience at Bowdoin. She said that she doesn’t feel pressure to hurry through work at the College, a feeling she likely could not find if she worked outside of higher education.

“At Bowdoin we focus on doing a good job, without the pressure of making money,” Mocarski said. “So if something takes longer to get right, we have the support to do that. It’s a good place to learn.”

The labor shortage’s effect on housekeepers

Segal’s study also comes as the College is facing a labor shortage and high turnover rates in housekeeping—something that administrators say is reflective of broader market trends. A few housekeeping employees, on the other hand, say it is caused in part by an unbearable workload.

“We’re so short-staffed that this isn’t sustainable,” an anonymous employee in housekeeping said. “And so we can’t be that meticulous in our work if we have the work of two or three people and we don’t even make the pay … to do the extra amount of work.”

“We once had 60 housekeepers, and it’s easier to be meticulous when you have two people in a freshman dorm or in certain buildings to get all the dusting—the walls, the floorwork—done, as opposed to the one person they have in there now,” the same employee said.

“It’s like we get people and they stay two months and leave…. [Housekeepers get assigned a new building to do by themselves] and they don’t know that that building used to be a two-person building until someone tells them and it’s exhausting,” another anonymous employee in housekeeping said.

Orlando said the turnover in housekeeping is reflective of national trends of turnover and labor shortages in housekeeping.

“Bowdoin was not immune to the Great Resignation that happened across the country in the wake of the pandemic, and housekeeping positions are one of those jobs that have experienced high turnover,” Orlando said. “We had a workforce with many that were approaching retirement age, and they decided to move on from Bowdoin, and we’re doing the best we can to fill in behind them.”

Associate Vice President for Facilities & Capital Projects Jeff Tuttle responded to the anonymous quotes above in an email. He noted that Bowdoin has 12% fewer housekeeping staff members than is standard for the College, which is similar to peer institutions. Housekeeping, he said, has adapted to accommodate these shifted numbers.

“Over the last few years, we have increased the amount, and type, of equipment that we use to gain efficiency, along with reducing the scope and cleaning frequency in many areas while maintaining a suitable standard of service,” Tuttle wrote.

“We have also been supplementing our efforts using outside cleaning contractors to clean areas that we once did in-house to lessen the burden on staff. That will continue until our staffing increases. We have also developed an onboarding program with a minimum four weeks of hands-on training with our infield trainer and team leader to aid in retention,” he wrote.

The first anonymous employee said the College’s responses seem like a defense of mediocrity.

“Bowdoin takes pride in a lot of its leadership and work to remain a relevant liberal arts college,” this employee said. “And I would like to see it be a leader in wages for their staff.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

This could be out of pocket, but what comes to my mind immediately is one word: endowment. How could an institution sitting on more money than any other in this state, pay a person so low that they are priced out of their community? I understand that this is not what an endowment is there for. I also know that in the end you have a surplus and you spend it, whether you are private or public. Five dollars means a bit more to a housekeeper than a scientist. –I’m glad there is an empathy in the school community.– You need to follow up with another article delineating the finances of Bowdoin. Otherwise this piece has zero heft or sway.