James Bowdoin promoted settler-colonialism

April 1, 2022

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Perrin Milliken

Perrin MillikenBefore he became the second governor of Massachusetts, and before his son named a college after him, James Bowdoin II was a financial magnate who started a war so he could steal Wabanaki land. In this reading of his life, Bowdoin was not just complicit in continuing what Penobscot scholar Donald Soctomah refers to as “the world’s largest genocide”—he and his business partners, supported by the British military, provoked a deadly war against Wabanaki people. James Bowdoin’s legacy is complex, but not ambiguous, and I hope this piece encourages Bowdoin College to put a long footnote wherever his name is invoked. Here is a beginning for that footnote.

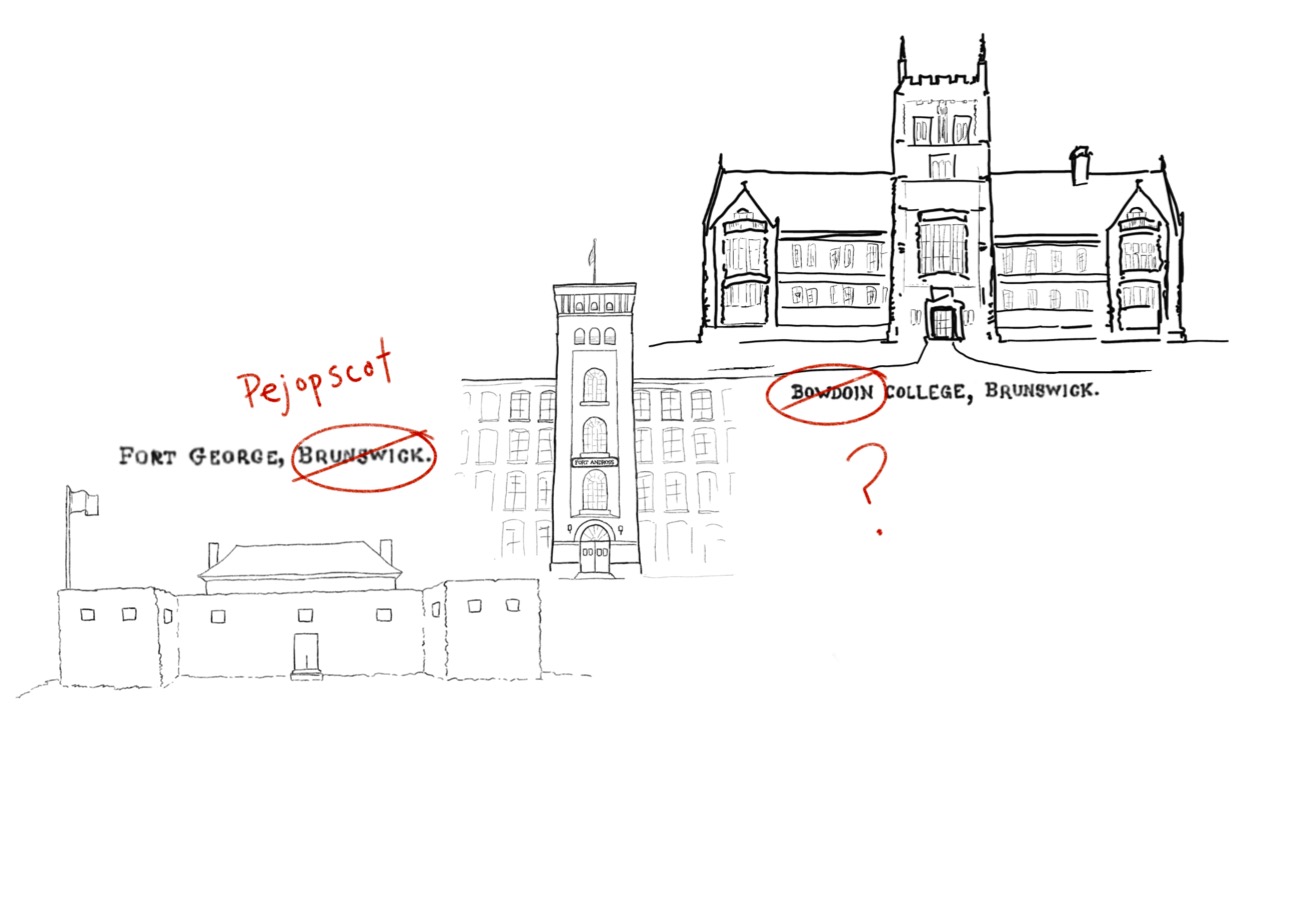

During King Phillip’s War (1675-1678), King William’s War (1688-1699) and Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), Wabanaki people repelled English settlers from what is now mid-coast Maine, though at a great cost of life. British settlers’ military forces, however, insisted on maintaining a presence in the “Eastern Country” through forts, which also served as trading posts. Around 1688, Governor Edmund Andros (namesake of Brunswick’s Fort Andross) strategically placed forts at river choke-points, such as Brunswick’s Pejepscot Falls (Fort George) and a narrow point of the Kennebec (Fort Richmond), to devastating effect. Historian Zachary Bennett writes that “Andros’s forts circumscribed Indian mobility, deprived them of food, and expanded sightlines far into their settlements.” The surveillance state had come to Maine, Bennett continues, “making Wabanaki submit, like bridled animals, to the designs of British imperial rule.”

In the first decades of the 1700s, investors from Boston revived the system of forts to protect English settlers re-colonizing the region. Wabanaki complained to British officials about the constricting effect that the forts and settlements had on their fishing and canoe travel, but these complaints went unresolved. Wiwuna, a Sagamore along the Kennebec, insisted in 1717 that the British build “no forts in the Eastern Parts,” and no settlements “adjacent to where my canoe can go.” Disregarding these requests again, investors encouraged settlers to come to Pejepscot, later renamed “Brunswick” to symbolically erase Wabanaki presence, and to settle along the Kennebec River valley. These actions sparked Drummer’s War (1722-25), “in fact a war provoked solely by the endeavor of the proprietors to settle the lands lying on the lower Kennebec and Androscoggin,” wrote historian Charles E. Nash. Businessmen had become war-hawks to extract profit from territory that was not theirs.

Enter James Bowdoin II. For twenty years, from 1725 to 1745, English colonists were granted a respite from fighting, though the Wabanaki who had been driven from the coast surely would not have called it peace. Fort Richmond was the northernmost boundary of English settlement, serving as a de facto territorial border. Meanwhile, Bowdoin and his associates in Boston formed the Kennebec Company, which had reportedly inherited a deed to fifty miles of land north of Fort Richmond (“bought,” despite mistranslations and misunderstandings, in the mid-1600s for bread, beans, cloth and three bottles of alcohol). Theirs was a “scheme of imputing value to the scrawls of ancient sagamores,” Nash wrote. It was contrived, and they knew it. In Nash’s history, a Wabanaki spokesperson argued that early colonizers had probably used rum and wine to obtain the land title from a Sagamore’s drunk son one hundred years earlier. The title mysteriously reappeared in 1741 after being lost, but the widow who held the deed did not wish to part with it. In something worthy of a movie villain’s scheme, Bowdoin’s associates stole the deed and established their land grab on that piece of paper. The entire incident remains an apt metaphor for the violent bait-and-switch that appeared to legitimize English occupation of the Kennebec River.

Let no doubt remain that Bowdoin was instrumental in seizing land from Wabanaki communities. Historian James W. North called him, “the most efficient and influential proprietor in causing the limits of the Kennebec Patent to be extended and established and its titles confirmed.” In addition, Kennebec Company investors encouraged Germans to settle in present-day Dresden to displace the Wabanaki communities. This tactic, touted as “the best means of developing the economic potential of the province,” is what historian Alexandra Montgomery calls “weaponized settlement.” Under these pressures, a fifth Anglo-Wabanaki War was fought from 1745 to 1753.

James Bowdoin was present at peace talks at Fort Richmond in 1753. There, Sagamore Quenois asked the British for what could have been a lasting compromise: “Do not turn us off this land. We are willing you should enjoy all the lands from the new fort [at Dresden] and downward.” All parties agreed to this request.

Not a year later, however, the investors financed a series of forts and settlements in Augusta and Waterville, flagrantly defying the agreement with Quenois and positioning the British to march on Wabanaki villages and their French allies. By the time of the Revolutionary War, English presence along the Kennebec had become dominant. Many Wabanaki fled north or integrated themselves into the European-style towns. James Bowdoin’s land grab had succeeded.

It would be easy to make a connection here with Jeffery Amherst, namesake of another college, who deliberately infected Native people with smallpox, on the basis that both were elite, colonizing men. But using the scholarship available today it may be more telling to connect them through the idea of biopolitical warfare. In these cases, writes groundbreaking essayist Amitav Ghosh, “English settlers believed they were less cruel … because instead of military violence, they were using ‘material forces’ and ‘natural processes’ to decimate indigenous peoples. This belief is so extraordinary that it requires a moment’s reflection…” Let us take that reflection. Consider why our college is named after someone who justified his actions with the idea that the extermination of Native peoples was natural—and then proceeded to strangle his enemy with “a state of permanent (or ‘forever’) war.”

These settler-colonial wars were fought over the identity of a people, the rights to access the land and waters and the right to be safe from violence. We are seeing the extension of these slow, largely-unremembered wars play out today as Wabanaki people and their allies clamor for justice. Bowdoin’s name is a sobering reminder of the settler-colonial ghosts that we still dance with today.

Holden Turner is a member of the Class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: