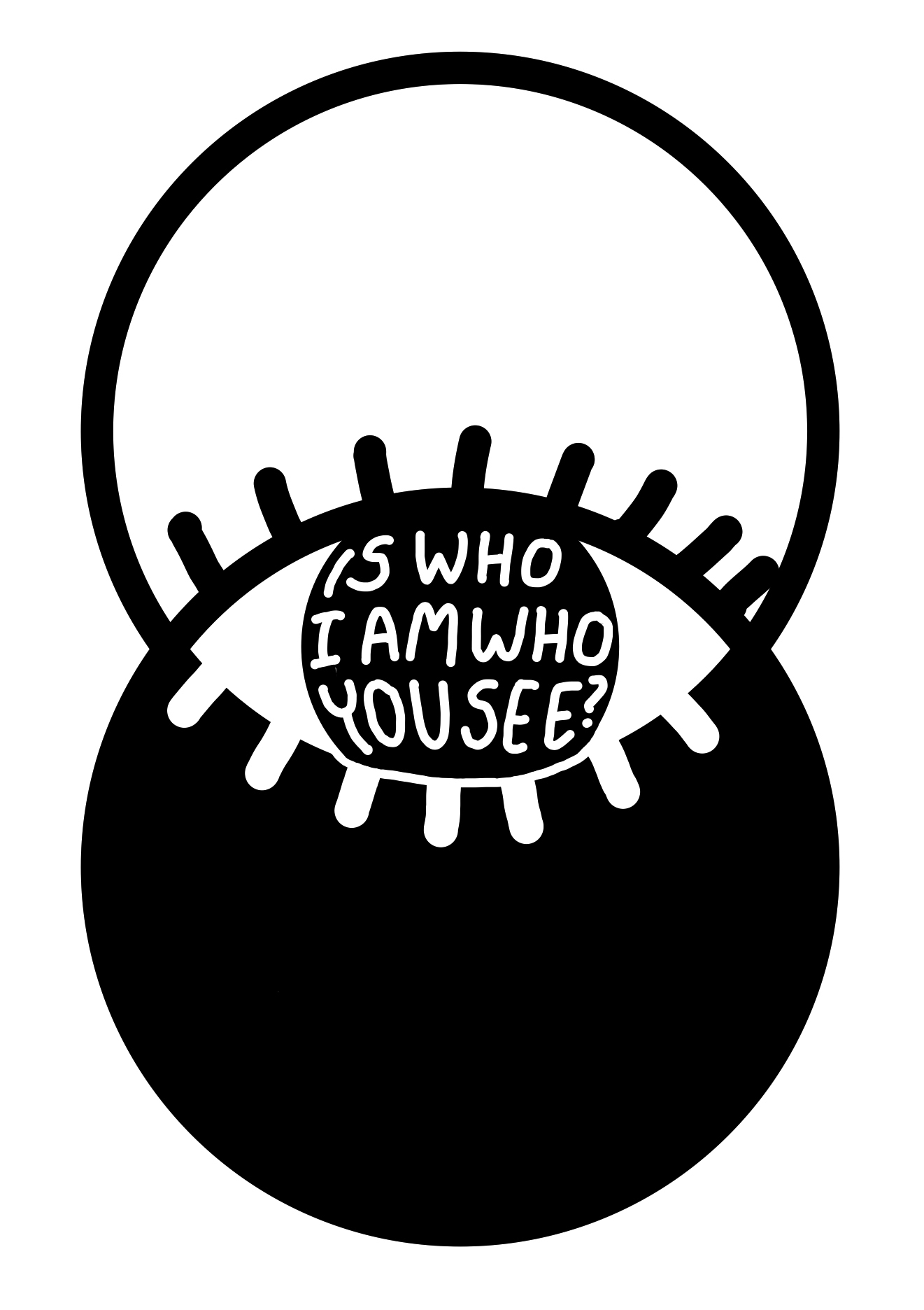

Is this our identity?

May 7, 2021

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

It sucks believing you’re the smartest Black person in the room. And it sucks even more having people believe that because you’re the smartest Black person in the room, you must be an exception to the norm, a deviation from your race, a “white” Black person. In my youthful ignorance, I was convinced that this sentiment was a compliment from my white peers. My perceivable intelligence had granted me access to their culture, which instilled pride within me. So I fully took on my role, separating myself from the other Black students who apparently weren’t as smart as me and the other white students. What I didn’t realize was that I was very much not assimilated into their culture, despite my best efforts. After all, I was still Black.

But every once in a while, I would meet another Black student; one that also seemed to be an exception from the others. Like myself, they would also be in all the advanced academic classes and tend to take interest in activities and topics not necessarily popular within the Black community. My friend, Alexandra, was one of these individuals and served as almost an ally, allowing me to find comfort within my behavioral distinctiveness. Around her, I was no longer a “white” Black person but a Black person who just happened to deviate from the perceived stereotypical normality of Blackness. Of course, our alliance didn’t completely allow me to find comfort within my racial and personal identity, and I would often find myself uncomfortable within homogenized Black environments. Why? Because I was still an “anomaly” to my race; I was very much still the “white” Black person my peers had deemed me to be years before.

However, around tenth grade, I began to feel somewhat embarrassed by my “whiteness,” particularly as an athlete on a pretty racially diverse track team. While I wasn’t necessarily interacting with them on a daily basis, when I was around the other Black sprinters and jumpers on the team, I would feel hyper-aware of my “non-Black” personality. They would visibly treat me differently than my other POC-identifying peers, regarding me as the quiet, smart girl who just happened to be athletic. It wasn’t necessarily true that they had a problem with me as an individual, but I was also never included as a member of their community. Even my coaches regarded me differently than the other athletes of color, instead associating me more with my white counterparts.

I don’t think either party was making a conscious decision about how to interact with me in comparison to my peers, but their perception of me was based on stereotypes associated with Black culture—stereotypes that I apparently didn’t conform to. Unfortunately, their doing so caused me to reevaluate my racial identity and, furthermore, my place within my community as a “white” Black person. In other words, would I ever find a place where I could express my true personality and various “non-Black” interests while still being fully accepted as a Black individual? Or would I always have to “fake” my Blackness in order to find solace within a POC-dominated environment (something I learned how to do later on in my high school career)?

In other words, I was stuck. Should I continue to be the unconventional Black person who was constantly associated with her white peers, or should I “fake” my Blackness in order to fit in with my people? Of course, I eventually opted to settle for neither—understanding that my racial identity, while culturally defining who I am, doesn’t dictate my academic competency or non-academic interests. However, this didn’t keep me from questioning how society has somehow made “being/acting Black” an entire personality. If you’re not Black, you’re not, and if you are, you are. It’s as simple as that, and yet, within our American culture, that is very much not the case.

Though I wouldn’t call myself an expert on Africanist culture or its roots within Black American culture, the informal yet immediate observational research I have done over the years leads me to a few conclusions about “Blackness.” For one, in order to be perceived as truly Black, one needs to be funny—comical even. Inside their classrooms, these Black students are usually the class clowns, if nothing else, and others, regardless of their racial identity, flock towards this individual’s magnetic personality. Academically, they may work hard but generally aren’t in many/any high-level classes (perhaps limiting their visibility in homogenized white circles). However, they exceed athletically in basketball, football, track and other sports dominated by Black athletes. They should also express somewhat of an effortless coolness, walking the hallways and streets with a sort of flair and swag-like composure that many consider attractive. Their style and fashion tastes should align with the typical “Black Instagram baddie” characterized by having long lashes, laid wigs and perfect edges, or it should match up with the general streetwear trend popular in social media today. And in terms of music taste, they listen to hip-hop, rap/trap, R&B and other genres dominated by Black artists—but strictly avoid metal, rock, country and international music styles such as K-pop.

I don’t want to say that there’s anything wrong with being interested in or behaving in the ways listed above, but some of those characteristics are actually linked to racist ideals that perpetuate negative stereotypes about Black individuals. There’s no reason why academic competency should be linked to whiteness when intelligence in no way correlates with race. And why must we always link humor with Blackness? It’s natural to be funny and to find certain individuals particularly playful or comical, but when we’re constantly deeming Black folk to be the most entertaining person in the room, it seems to encourage the persistence of historically racist caricatures. Aside from the racism that lies underneath many of these designations, solely assigning one very stereotypical personality to an entire racial group is dangerous. By doing so, we are essentially invalidating the individualistic and nonconforming characteristics of many people within the said community. As a result, particularly young Black individuals, like my past—and arguably current—self are excluded from the very culture that is supposed to encourage and support all that makes them who they are as people.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that we need to do a better job of making sure we don’t throw all Black folk into a box of conformity. Yes, ‘to be Black’ is a state of being that transcends the physical. In fact, much of our experiences, ancestral values and everyday problems have permeated themselves into our collective identity. But all Black people have aspirations, interests and talents that don’t necessarily match that of another—and it doesn’t, nor should it ever, invalidate their Blackness. Of course, these are just thoughts in passing.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

This article rings true, much more then modern society thinks. I’m Hispanic, and yet the social stereotypes and habits associated with being a Hispanic individual have no relevancy to my person. Maybe it’s due to my upbringing? I wasn’t raiseyour ongside my cultural values like every other Hispanic I know typically is. From the everyday lingo, to social activities- it’s very clear to me that I don’t identify with those “norms” like many would expect me to. And they shouldn’t either, it’s not like I go out of my way to be accepted into their groups, despite having tried that and feeling quite awkward and not at all “free to act out in my racial blood” by any acceptable standards. To be frank, it sickens me. For someone to take one glance at you and assume all that you’re about has been very detrimental to my openness in regards to my ideas. I shut down my true thoughts, and go to “autopilot Hispanic responses* out of shame that I’m not being the ” true blood Hispanic” everyone expects out of me, even if they won’t say that to my face. Thanks for sharing your opinion, much appreciated as always.