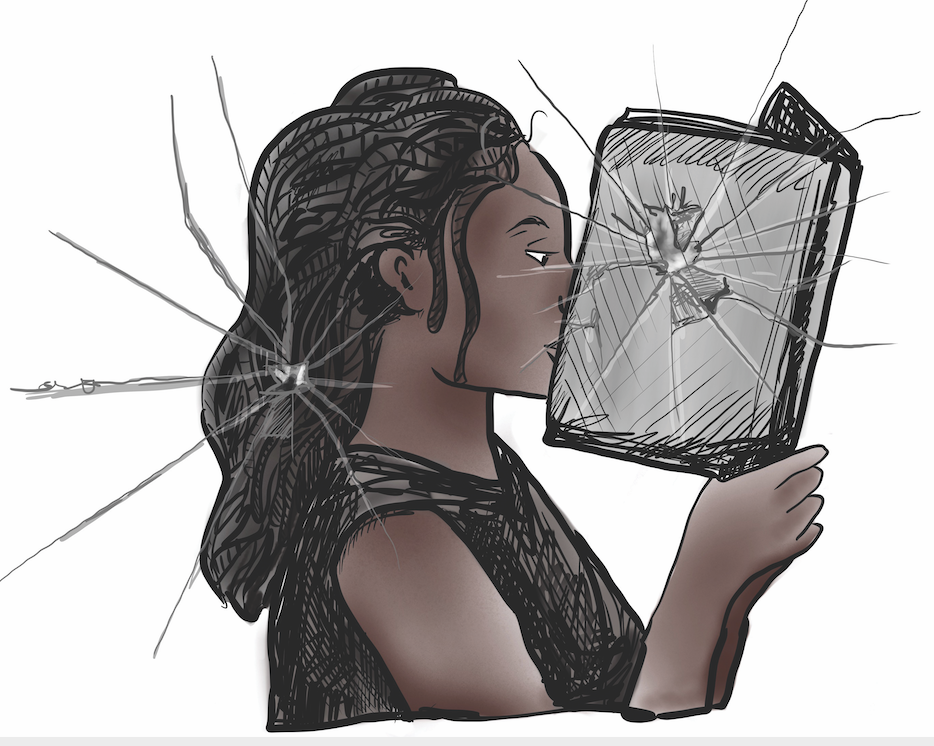

No rest for the weary: emotional exhaustion as a Black woman, from last summer to the present

April 30, 2021

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Dalia Tabachnik

Dalia TabachnikI did not come to campus last semester eager-eyed and bushy-tailed. Instead, I came anxious and afraid. Of course, starting college in a literal pandemic did cause some anxieties to arise. I knew that academics would be more difficult online, and I expected that socialization would be more awkward, as I am already a pretty introverted person. But, more importantly, I was hyper-focused on how my identity as a Black woman would affect my college experience, especially in a state that is 94 percent white.

Although the summer of 2020 was emotionally draining, as I detailed in my first article, it was exhausting for a different reason: it was burdensome to always have the aforesaid thoughts about race at the forefront of my mind and to have my emotional and mental guard up for this reason. I began obsessively perusing social media pages that listed everything from microaggressions to the horrific macro-aggressive actions that Black students, especially Black women, experienced at predominantly white institutions (PWIs).

The mental notes that I made were countless: if a white guy shows interest in you, know that it’s not because he has an interest in you but rather an interest in satisfying his fetish. You’re not athletic anyway, but be sure to avoid athletic team spaces because they seem to be racism breeding grounds. If someone tries to touch your hair, be prepared to defend the right to your own body and personal space. You may have imposter syndrome, but if a rich kid questions why you deserve to be here, be prepared to defend yourself and your existence at this school. Don’t go to parties; otherwise, you’ll catch a case of COVID-19 and the cops.

This hyper-obsessiveness seeped into my academics, too. I approached classes with gusto, determined to prove to myself that my admission to this school was not a pity case and that I actually deserved to be here. It was as though I was constantly trying to work against the stereotypes associated with my background; I needed to prove that I was neither a lazy Black person nor a first-generation low-income (FGLI) student who was just an affirmative action or diversity quota admit.

I can’t say that I gave myself much grace last semester; in my mind, missed opportunities to participate in class, for example, were strikes that I counted against myself, little points that I knew would come back to bite me at the end of the semester. Being unable to decipher dense readings just drove me to race against time, seeking to fill my gaps of knowledge as quickly as possible, as opposed to saying, “It’s okay, it’s your first time reading texts like this, you’ll get it with time.” Above all, homework mistakes were like death sentences to me, and the phrase “first impressions are lasting impressions” haunted me, making me work even harder to scrub away at what felt like bad first impressions I made on certain professors.

With this in mind, I trekked across campus with a guarded heart: disappointed that I was the only Black woman and FGLI student in a College House full of mostly white students and athletes, and unwilling to become the token Black person in the watered-down discussions about race and “inclusive language” the College put on at the beginning of the semester. As I should have expected, conversations surrounding race and social justice issues died down as quickly as they were started. But you know what? I was happy, believe it or not, not to have to talk about race. I hated seeing people contort their faces into fake expressions of care. On top of this, I was just so damn tired about talking about Black pain and the dead—no, slain—Black people who we grieve for, both consciously and unconsciously. And so I basked in this silence, until I realized that by being complicit in not discussing important social issues, I was actually rendering myself invisible. I thought that pretending that these problems didn’t exist would help me better assimilate at Bowdoin, and I even tried to think similarly to, if just for a short amount of time, my white peers, to whom race is a mere afterthought. In reality, this just alienated me further from my own emotions as I buried my grief deep within my mind and burrowed myself in my work instead.

I’m afraid that now, even though I am aware of the feelings that reside within me, if I take the time to fully look into them, they will gush out of me like water from a broken tap, my grief leaving me unable to do what is supposedly of the greatest importance: my schoolwork.

But because George Floyd’s killer, Derek Chauvin, was found guilty, I should be feeling slightly better, right? No. Sure, it was a victory, albeit a small one. But above all, it is a gross overstatement to say that justice was served, especially when we know that it is a systemic issue at large. That is why Pelosi’s comment, that George Floyd “sacrific[ed] [his] life for justice” makes me physically sick—he was not a willful martyr but a victim slain by the manifestations of this country’s racist institutions and unjust systems.

Remarks like Pelosi’s, irrespective of party affiliations, serve as a constant reminder that Black bodies are seen as commodities. We are capitalized off of by politicians, the media and photojournalism in particular. Of course, Black pain has always been a spectacle for white audiences; for example, the word “picnic carries” deep associations with “pick-a-nig,” where white families would eat boxed lunches around a hanged Black person of their choosing. So I suppose that it shouldn’t surprise me that white people do virtually the same thing today.

But do they really sit through the clips of Black people being slaughtered on T.V. in between bites of chicken and sips of wine during dinnertime? Or watch the full video of an incident of police brutality, phone in one hand and iced coffee in the other? The ease with which white audiences consume Black pain is dystopian, almost psychopathic, and it occurs at the expense of, of course, Black people. Videos of people like me gasping for their last breaths or being abused by the people who are supposed to protect them are circulated throughout the internet, encouraging people to WATCH but never listen. And better yet, none of the videos that feature actual people dying have trigger warnings, but you best believe that their sacred animal cruelty videos have slews of them.

Because of this, from a very young age, I have been emotionally and mentally aged by the recurrence of police brutality in this country. After all, I turned 18 not last February, but rather when I was 10, after I learned that Trayvon Martin was killed for existing within a Black body and wearing a hoodie to buy snacks from the corner store— something I do all the time. Turned 18 again when I was 12 and Michael Brown was murdered in the summer before his first semester of college. Turned 18 when I found out that Breonna Taylor’s killer was given a book deal with a major publishing company. Reminded of my adulthood just last week as media outlets constantly perpetuated adultification bias by painting the late Ma’Khia Bryant, who was just a few months older than my 15-year-old younger sister, as a young woman instead of a young girl.

But in spite of all this, I persist. I don’t ask my professors for breaks—not because I am any better than students who do, but because this country has forced me to work through grief from a young age, and I have now become used to it. And so I squeeze my eyes shut and furiously shake my head in an attempt to remove the fragments of these images and videos that exist within me, shades of brown and ringing gunshots and pleas for survival blurring in my mind, knowing that my utmost priority is not myself, but rather whatever readings and assignments I have for the week.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: