The descent into the abyss

October 25, 2019

Courtesy of MIT Technology Review

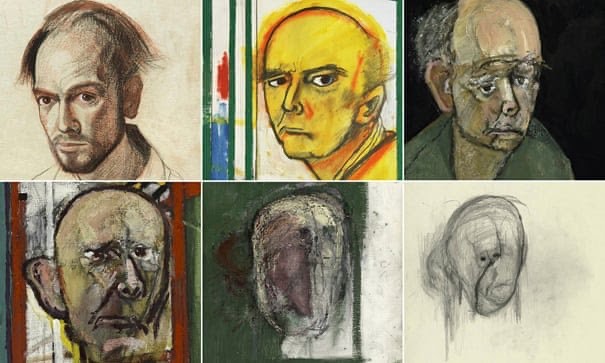

Courtesy of MIT Technology ReviewThese self-portraits were made by William Utermohlen, a 20th century contemporary artist. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1995. At the onset of his Alzheimer’s, he decided to sketch a portrait of himself once a year until 2000—he died in 2007. I remember Christoph Straub, a visiting assistant professor in neuroscience, showing me these drawings in a class on neurological disorders.

The drawings were troubling to see because Utermohlen had the courage to display his own deterioration while still living. These drawings also offered me a way to view my father’s degeneration. Art, in a way, widened my perspective and provided me with a strange empathy.

After countless diagnoses and brain scans, my father was recently diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) at the age of 52. He is suffering, both in mind and body, and I’m not really sure he knows what is going on. It’s as if a monster has overtaken his consciousness, and he can’t control it. When I look at my father in his present state, I am reminded of a quote by Frederick Nietzsche: “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.”

My father is fighting monsters and has, at times, been a monster. Sometimes I am scared of the words he mutters under his breath: “They’re eating you alive,” “They’re ripping your body apart.” Other times he stares into a mirror and looks as if he has fallen into the abyss, or as Dante would call it, the Inferno.

My family and I struggle to figure out how to deal with the reality of Robert Welch, my father. Sometimes the solution is to cry, other times it’s to laugh, but the most fervent emotion in all of us is anger. Anger at what? Some God who made him this way—a force or energy in the universe we can’t control. Fate.

Sometimes I choose to be angry and embarrassed at him for his FTD behaviors. Other times I find myself laughing at how he wants to eat at McDonald’s every day and walk 10 miles up and down the same street. Whether it be laughter, sadness or anger, the special moments are the ones where I can see my father for who he was. These moments are when I can accept my father and feel complete bliss.

But, as you know, these moments of happiness are like a butterfly. As Lana Del Rey writes in her new song, “Happiness is a butterfly, try to catch it like every night. It escapes from my hands into moonlight.”

Once the moment escapes from my grasp, I go back and forth fighting some way or another for something more in my father, something that will never be there. But then I ask myself, what if it’s not about fighting the past or the future situation, but about accepting my present situation? I tell myself to accept his condition, accept his impending death.

Sometimes I can accept it, but other times it’s a fight between me and my will. In “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” James Baldwin writes of acceptance: “But our humanity is our burden, our life; we need not battle for it; we need only to do what is infinitely more difficult—that is, accept it.”

Acceptance is the first step. My way of accepting my father is writing poems in an attempt to preserve his memory, enjoying sunsets at Sea Cliff Beach (his favorite beach) and facetiming him at night. Even though my father is not the same father from my childhood, I enjoy these times of bliss and invite him into my body.

As the Buddha says, “I am aware that my father is fully present in every cell of my body. I invite my father to breathe in with me. Breathe out with me. I would like to invite my father in me to sit with my back—this is my back, but it is also his back. Father and son. Father and daughter. Breathing together.”

Now all this may sound trivial and simple, but I thought my father and mother would live forever. Then, reality set in. My first reaction was to deny his diagnosis, avoid confrontation and imagine that he would be the same father I had since childhood. Unfortunately, I was wrong. I had no choice but to accept that my father will die before most mothers and fathers do. The situation still doesn’t seem real to me.

As I continue to write poetry and try to catch the butterfly, I begin to realize that these moments are what I live for. It is a hunger to exist that I believe is unique to the human condition.

Dylan Welch is a member of the Class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

This was beautiful. Thank you, Dylan, for sharing.

Thank you Nate, much appreciated.

You are a very strong young man Dylan looking the beast, FTDdementia in the eye & shaking a metephorical fist at it. You are wise beyond your years. Your pure love for your dad shines thru in your writing. You are a brave warrior. You can do this. Those of us who have been there support you.

Beautifully written and very powerful. You’ve a big heart Dylan.