Why revising your past ideas is important

October 4, 2019

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Lily Anna Fullam

Lily Anna FullamI would like to revise my Common App essay. Thank you, admissions office, for seeing the potential in what I wrote and inviting me to enroll, but my priorities then do not match my beliefs now. And for this reason I have a few changes to make.

I wrote my essay reflecting on a multi-day outdoors experience in a close-knit group. This sort of theme is not unique: camping programs, backcountry experiences and even family trips are excellent topics to explore when looking for personal qualities to express to college admissions and I admire those of you who submitted one of these for your love of the places you saw and people who joined you. These memories contain crucial lessons. I applaud what you wrote in your essays about leadership, inner strength and stewardship of beautiful landscapes.

The issue that I take with my own essay is that I wrote it as a blind lover of wilderness. Bowdoin courses have changed that. Four semesters in the Environmental Studies (ES) program here will not let anyone get away without confronting this word, “wilderness.” American scholars have interrogated the concept and found it complicit in unjust treatment of people and landscapes. According to what is read in ES classes, the wilderness myth has supported the Romantics and their erasure of other cultures, the conservationists and their urban-centered objectives and the deep ecologists and their radical actions against development. While this is far too general of a summary, the theory is not my subject matter here. Knowing what I know now about the history of the term, I would choose to take back some of what I wrote.

To quote myself at age 17: “It’s so liberating to be in the wilderness!” I recall writing this while staring into a deep and dark maple forest next to my tent. I reproduced it verbatim in my essay to show how I reveled in an authentic sense of place. Another example of what I wrote: “Wilderness should not be taken lightly.” This time, I was referring to the lichen on rocks above the treeline. Hikers should know this alpine ecosystem is very fragile. I imagined I guarded life from the polluting impact of our footsteps. I wrote about its fragility to show that I could be a protector of vulnerable places. I thought wilderness was inherently valuable. I thought wilderness always implied getting nearer to the quick of life. Out of the 650 words allotted for the Common App essay, I used the word “wilderness” seven times. All the better to sketch myself as an advocate of the best land in our country.

But this is what I just wrote in the margins of my readings: Wilderness cannot be an end unto itself. I smile at the irony. Three years ago I believed fully that I would support the wilderness preservation movement in college, but learning more fully about the public lands problem—and about any complex issue—now gives me pause. And makes me want to revise. And revise. And revise again.

When once I wrote that I felt free in the wild, I now cringe to think of my tactlessness in acknowledging why I could feel the privilege of freedom in this space. In this case, I was further supported by precedent of my cultural ancestors. Male Anglo-European writers had also written of their awe when walking under bare-topped mountains and through pine forests. And though I intended to describe fragile ecosystems, I also reproduced the problem of denying that humans had domination over the land, and calling that natural. My experience was not in pristine nature – it was in a landscape set aside to seem that way. Its architects intended to deliver the sort of experience I wrote about, but that experience is an illusion. An American landscape has not gone untrammeled by human actions in any recent history.

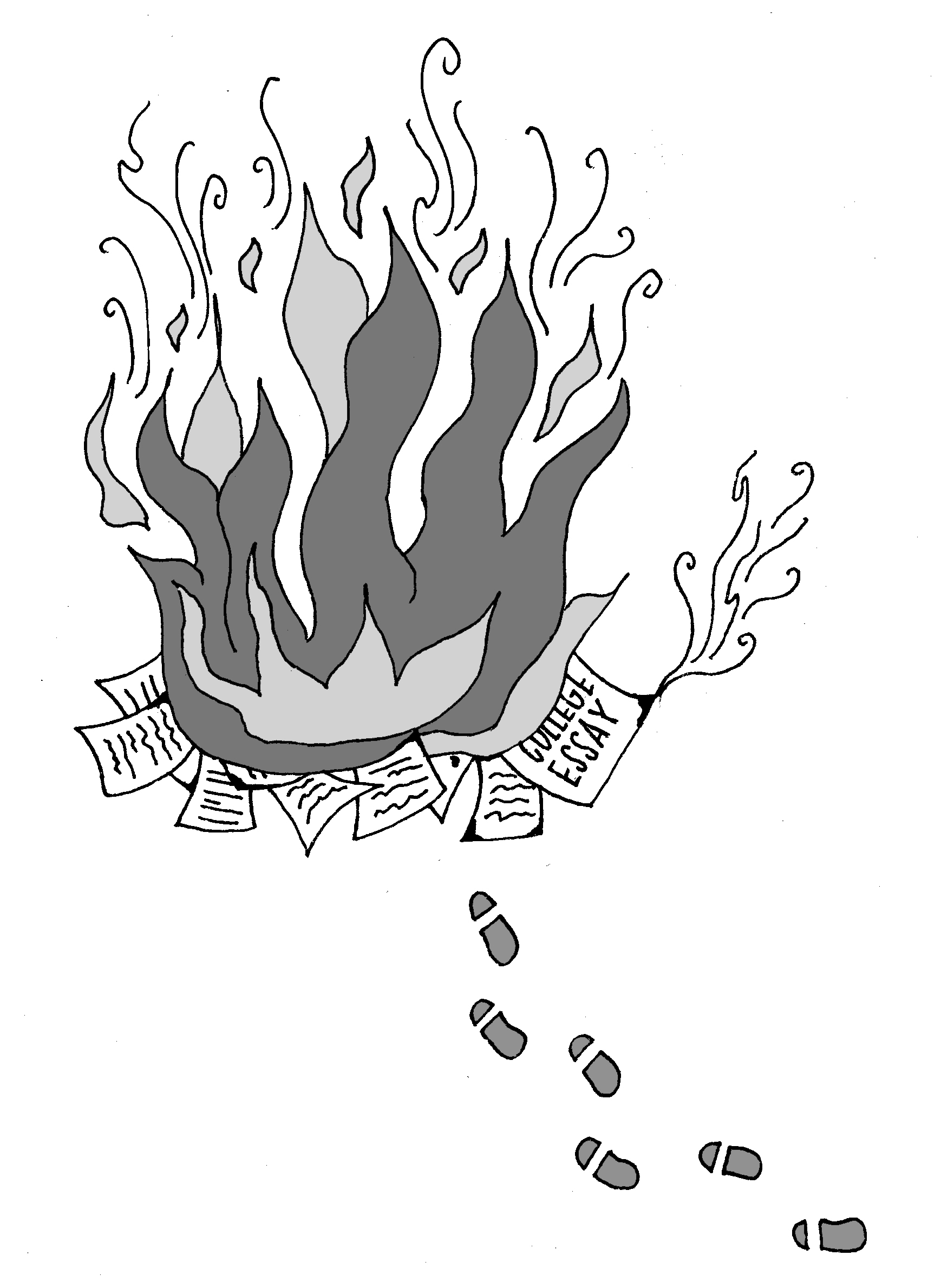

Reckoning with my essay now leaves me hoping to start over from that story I was trying to tell about myself and makes me try to think more carefully about the weight of every word before I set it down in type and have it diffused across whoknowswhere. My essay was not written carefully. But painstakingly choosing words has me questioning the effect of each one before I cause an impact of some unknown rippling reach. This logophile’s anxiety makes me want to commit: that I will not hesitate to take back my words when I speak in ignorance. And everyone speaks from a position of some ignorance. Talking of the wilderness when I was barely acquainted with the threads leading to and from that word is a good example. And so I would like to take back my admissions writings, maybe cast them like old journals into a fire, because they represent someone who is not me anymore. At least, I would not write in the same way now.

I’ll end this op-ed with a few questions to think over. For anyone who has recently written application essays that demonstrate your personal values: Are you prepared to find that after a year, or more, you may no longer see your topic in the same way? How might you revise your theme to respond to a greater awareness? And for those who wrote an essay years ago: Can you see any issues with what you once wrote? Would you revise it if you could? And how might someone come to terms with their past ignorance? This may seem like a small question, but its answer determines the difference between burning out of fear all the notebooks you ever kept and letting them accumulate on the shelf to keep you humble. For now, I opt to let the dust settle on my writings, and in the meantime I patiently nurture my words along until I am satisfied enough.

Holden Turner is a member of the Class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: