New exhibit honors 50th anniversary of Africana studies

September 13, 2019

Caroline Flaharty

Caroline FlahartyAt 3 p.m. today, students, faculty and staff will gather around five exhibit cases on the second floor gallery of Hawthorne-Longfellow (H-L) Library for the opening of “Tension/Tenacity: Africana Studies at 50,” an exhibition that explores the five-decade history of Bowdoin’s Africana studies program, the John Brown Russwurm African American Center and the Black Student Union (formerly the African American Society). The exhibit will be on display throughout the semester.

At this afternoon’s event, Special Collections Education & Outreach Librarian Marieke Van Der Steenhoven and student curator Lucy Ryan ’19 will discuss the content and organization of the exhibit, as well as Ryan’s research process and her experience combing through the College’s archives.

The exhibition opening is one of many events around campus that mark the 50th anniversary of the Africana studies program, the Russwurm African American Center and the Black Student Union, all of which were established in the fall of 1969.

Ryan began research for the project last spring and worked on the exhibit throughout the summer.

“I think one of the stories Lucy teases out is the story of how students influence both the academic program but then also the more co-curricular or social components of [the history which includes] speakers that are brought to campus, advocacy both on- and off-campus [and] creating the first African American Center in the state of Maine,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “There are these really fabulous ways that the history of this academic program, which is now fully supported by the administration, is very much a story of student activism.”

The idea for the exhibit came from Peter M. Small Associate Professor of Africana Studies and English Tess Chakkalakal and Geoffrey Canada Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History Brian Purnell, who thought an exhibit with materials from Special Collections would be the best way to showcase the history of Africana studies. Chakkalakal explained that displaying historical documents would allow people to engage with the material and develop a deeper understanding of how the Africana studies program is linked to the origins of the College and has become a cornerstone of a Bowdoin education.

“Lucy’s exhibit really clarifies the nature of those struggles and how Africana studies was this cumulative process that developed over time,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “And it seems to me that we’re now at a place very far from where it once was.”

The Africana studies program, Ryan explained, began to resemble the vibrant department it is today in 2008, when five new professors were hired, four of whom are still at Bowdoin: Chakkalakal, Purnell, Associate Professor of Africana Studies Judith Casselberry and Professor of History David Gordon. Olufemi Vaughan, the fifth 2008 hire, is now at Amherst College as the Alfred Sargent Lee ’41 and Mary Farley Ames Lee Professor of Black Studies.

Before 2008, the program struggled for four decades, Ryan said. Students, faculty and staff repeatedly asked the College to hire a new faculty member to join the single full-time professor in the department. Their requests were denied year after year, despite the fact that limited class offerings meant students were often unable to complete the major.

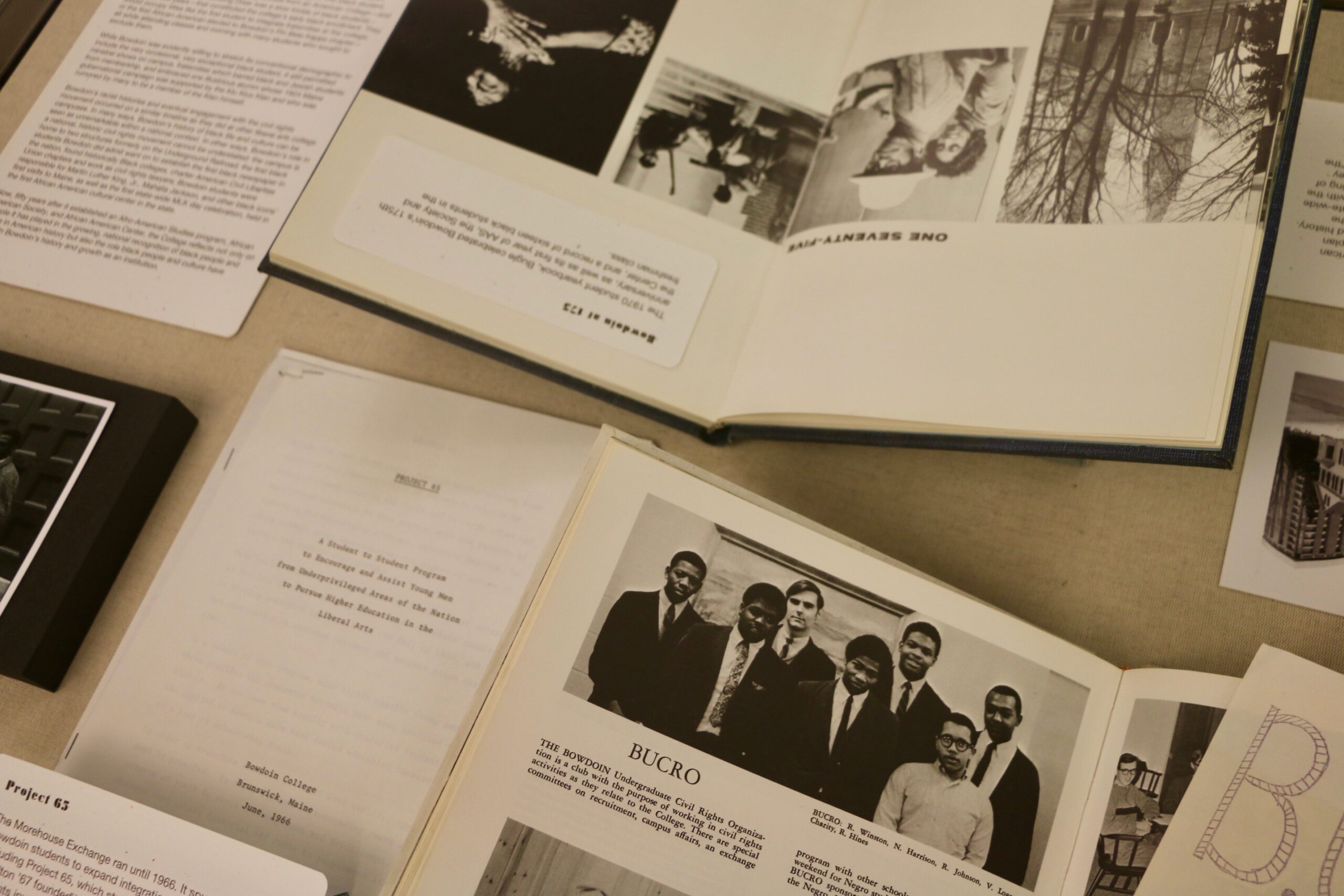

The five display cases are arranged thematically, explained Ryan. The first case, entitled “Inception,” examines the work of students, faculty and staff that laid the foundation for the programs’ creation in the fall of 1969, including the Morehouse Exchange Program, an admissions outreach program called Project 65 and the Bowdoin Undergraduate Civil Rights Organization. This work culminated in the establishment of the Committee for Afro-American Studies, which proposed an Afro-American studies major that would later become Africana studies.

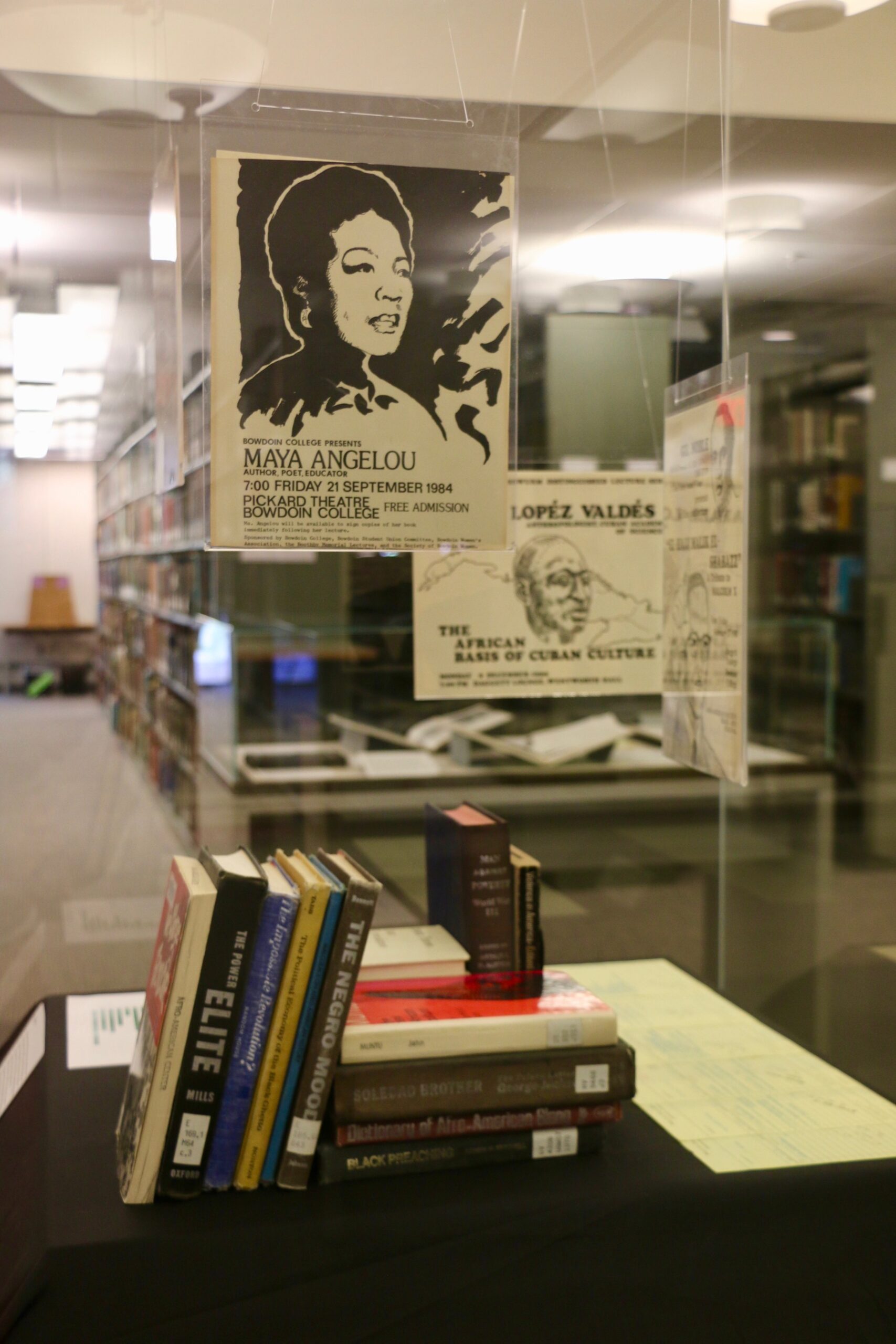

The “Student Power and Activism” case explores how students played a central role in keeping the program afloat. The “Leadership” case looks at the previous directors of the Africana studies program and calls attention to Bowdoin’s struggle to retain black faculty over the decades. The “Arrival” case includes documents about the 10th, 20th, 30th and 40th anniversaries of the program, and the final case, the “Intellectual and Cultural Life” case, includes hand-drawn posters, books that were in the original Russwurm library and a graph of the number of Africana studies majors since 1969.

Ryan believes the exhibit offers visitors the chance to engage with both the inspiring stories of student activism and the less progressive aspects of Bowdoin’s history. While her research centered on the period between 1969 and 2019, it led her to wonder more about the experiences of the approximately 20 black students who attended Bowdoin between 1794 and 1969 who may have been the only black students at Bowdoin for multiple decades.

Ryan explained that while Bowdoin was not technically segregated, she did not find evidence that the College consciously tried to accelerate integration until the mid-20th century.

Although she is grateful for the opportunity to commit herself to a project that allowed her to gain experience curating a historical exhibit, Ryan questioned whether she, as a white person, was the best person for the project.

“I can’t contribute my personal experience…on what it means to be black at Bowdoin,” Ryan said. “I’m still, as a history student, grappling with how identity politics plays a role in history telling, in the kind of history telling I want to do… I just poured myself into it and really approached it as, this is an effort in excavating the archives, [trying] to get every single perspective I can with what’s made available to me.”

For Ryan, showcasing the tensions from those perspectives and the tenacity of African American students was most important.

“It didn’t just take 50 years to get where it is today. It took 40 years of really slow progress and then 10 years of much faster progress,” Ryan said. “I think that’s where the tension/tenacity comes in, because it took a lot of faith year after year for the same professors and students, in their four years, coming back and fighting for the same things and advocating for the program.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: