There is only one Maine

January 25, 2019

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Lily Anna Fullam

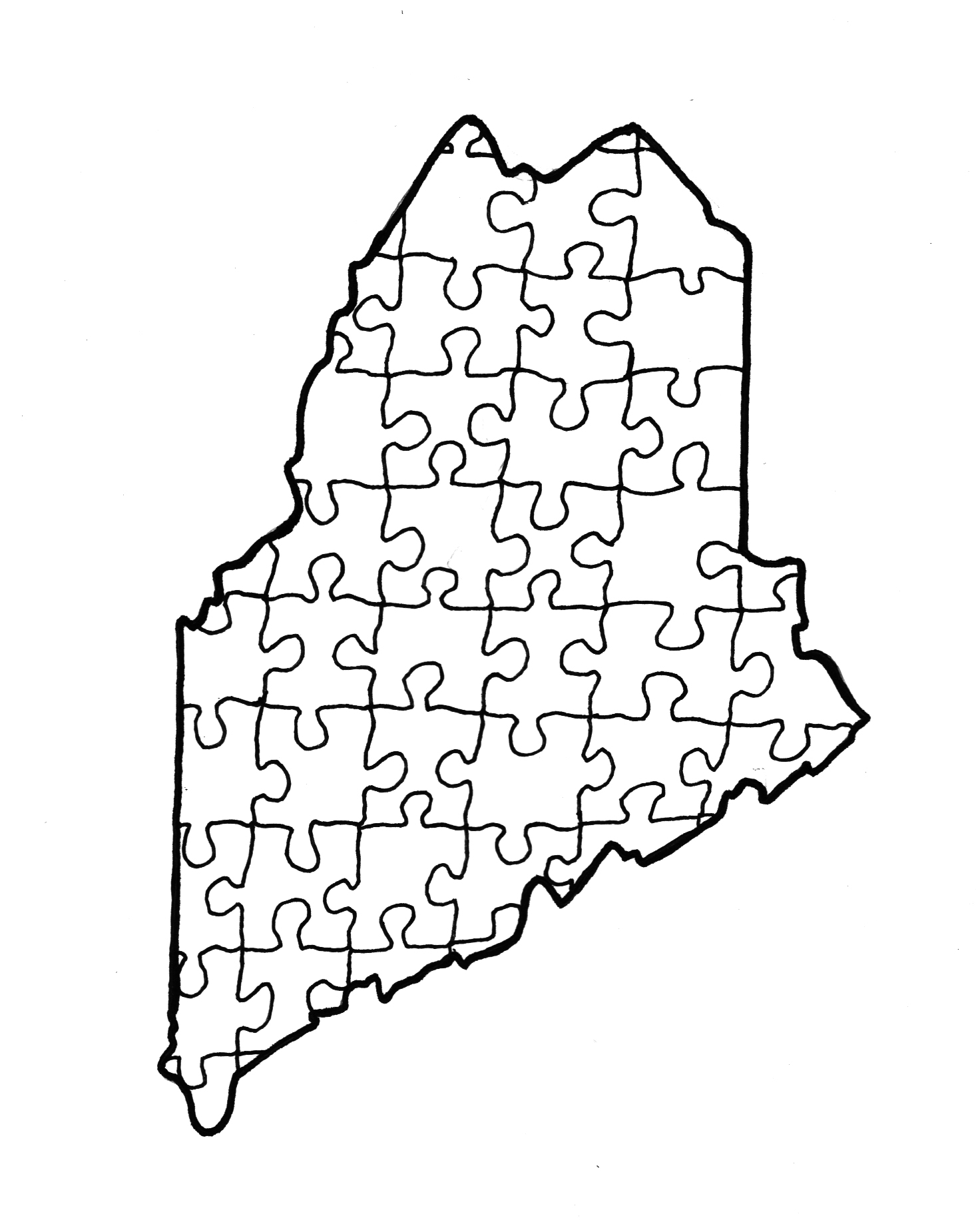

Lily Anna FullamIn her recent inaugural address, Maine’s new governor Janet Mills laid out an ambitious plan to bolster the state’s economy, combat the opioid crisis and address climate change. She also sent a strong message of unity to her audience, proclaiming, “We are one Maine, undivided, one family from Calais to Bethel, from York to Fort Kent.”

With this one sentence, Governor Mills did more than set a new course from the divisive LePage era. Namely, she banished the decades-old idea of a fault line in Maine’s cultural and political fabric, a division that supposedly splits our state into two distinct regions: a prosperous, liberal south centered around Portland, and a lagging, conservative north with a mostly diffuse population. I agree with her. While it’s tempting to adopt this generalized, geographically divided view of our state, especially when recent political maps have painted a picture of two separate congressional districts, the first blue and the second red, this isn’t a very meaningful division.

Maine isn’t neatly split between north and south, inland and coast or rural and urban areas. None of these models explains why a large swath of the Downeast coast tends to vote Republican, or why the St. John Valley on Maine’s northern border goes mostly for the Democrats. They ignore the myriad cultural subtleties that produce these patterns, from the distinct traditions of Acadians in Aroostook County to the habits of seventh-generation lobstermen in Washington County. It’s reductive to say that Maine, a state roughly the size of the five other New England states combined, can be lumped into just two monolithic cultural regions. Although people may act differently in Madawaska than in Kittery, the differences fall along a gradient. There’s no dividing line somewhere in the middle where one culture abruptly becomes the next.

It’s also worth noting that, though Cumberland and York counties on the whole are better off economically than Penobscot and Aroostook, this doesn’t mean that they and the rest of Maine’s sixteen counties don’t share many of the same challenges. Both areas were hit hard by the decline of industry in the 20th century that left crumbling textile mills in the South and struggling paper mills in the North. Traditional fishing communities along the coast everywhere from Portland to Eastport are threatened by gentrification and development brought on by wealthy newcomers. Mainers from Biddeford to Bangor have been devastated by the opioid crisis. It is detrimental to our progress as a state to assume that we suffer from different ailments.

In a time of increasing political and demographic divisions, it is dangerous to define Maine as two separate entities. Though Washington D.C. and the country appear more polarized than ever, Maine must not succumb to this mindset. As a state, we are known for our independent streak. Most of the Pine Tree State’s greatest politicians, from Susan Collins and Angus King to George Mitchell and Margaret Chase Smith, have risen to prominence precisely because of their willingness to reach across the aisle and to consider the voices of all their constituents. In the tradition of our statesmen and stateswomen, who, after all, perfected their craft in Maine, we must realize that compromise is still possible here, no matter what outside observers might say.

With new leadership in Augusta, it’s high time that we ditch our tribal divisions and get back on track. Governor Mills is right: there is one Maine, period. We may be diverse in regional cultures, but we have far more in common than we let ourselves realize. I look forward to this new era of progress and cooperation and hope that the new administration will continue to champion what binds Maine together, not what tears it apart.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: