Don’t do drugs

September 27, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

I do not advocate for the use of any psychoactive compounds. Nor do I advocate for their non-use. You can do whatever you want. Isn’t that beautiful? Our culture sees “drugs” as either 1. indispensably useful in medicine or 2. illegal, addictive, life-destroying, soul-sucking incarnations of Satan. We pretend that alcohol, a toxic and addictive compound, isn’t even a drug, hence the common phrase “drugs and alcohol.”

But what is a drug? To paraphrase Google’s broad definition, a drug is any substance that biochemically affects the body. Let’s restrict this definition to psychoactive drugs (those which “affect the mind”). We still have people who find time between their psychoactive fixes of caffeine, alcohol, painkillers, nicotine and sugar (yes, sugar) to tell others to not use drugs.

In this paradoxical, cultural climate, children are bombarded with fear tactics and misinformation but still can’t go a day without seeing an ad that glorifies alcohol on cable TV. Alcohol and tobacco are both addictive and toxic, harming and killing many people every day. However, some illegal drugs are not addictive, non-toxic and far less likely to cause any kind of harm. This lack of logic prevents many of us from seeing the very real potential for illegal compounds to benefit humanity. Psychedelics fit the bill.

There are many myths to debunk concerning psychedelics, but here’s the short version. You cannot get stuck in a trip. Bad trips are avoidable. LSD is not stored in spinal fluid; it’s gone in about a day. Psychedelics themselves do not create a permanent state of psychosis or schizophrenia but can expose a latent mental condition. No one with a family history of these disorders should use these substances. No one has died of an LSD, DMT or mushroom overdose, because most psychedelics are not toxic. They do not cause the brain to bleed or lose cells. They are not physically addictive and are only rarely psychologically addictive; the desire to use usually decreases with use.

Psychedelics cannot endow your un-drugged brain with the ability to spontaneously trip. Sometimes, after using, people can get minor, momentary visual distortions. Some get anxiety attacks due to PTSD from terrifying trips. A very small minority of users get HPPD (hallucinogen persisting perception disorder), in which slight visual distortions are experienced continuously after the drug has worn off, but it is extremely rare and usually short-lived.

Recently, researchers have examined the medical benefits of psychedelic drugs such as LSD and psilocybin, the active chemical in magic mushrooms. The results have been shocking.

A 2014 study at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) demonstrated psilocybin’s ability to catalyze smoking cessation. With a success rate of 80 percent after six months, it is currently the best treatment known. Only three doses were required, which is unprecedented. Also, psilocybin has been shown to kick other drug addictions, such as alcoholism.

In a 2016 study at Imperial College London, psilocybin successfully diminished or eradicated treatment-resistant depression and anxiety. Sixty-seven percent of participants were depression-free for at least a week, and 42 percent were for three months or longer. This was after just two doses.

A 2016 JHU study showed that psilocybin helps cancer patients who experience existential distress and depression after a terminal diagnosis. Patients showed significant, positive changes in mood, behavior, altruism and attitudes about life and death. After six months, 67 percent of participants still reported their high-dose session to be in the top five most meaningful events of their lives, and over 80 percent experienced increased well-being and life satisfaction. Only two doses were administered.

Psychedelics create a different, self-critical perspective, letting people see how they are hurting themselves. They make people reorganize their values and understand different things to be most important. They make people emotionally experience truths that they only understood intellectually before. For example, one life-long smoker quit after psilocybin helped her emotionally experience the myriad possibilities and value of life.

In the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, similar strides were made in studying the benefits of LSD. However, the moral panic over psychedelics led to illegalization and a halt on research. Knowledge was silenced, and hysteria got the mic.

It is unfortunate that the pharmaceutical industry is not interested in investing in psychedelic treatments despite the positive and repeatable results. But it makes sense. You can’t make money off a drug that most people only need a few times.

Legalization of medical psychedelics is probably not far off, though. Like in the case of marijuana, the research on these drugs will probably be enough to break down the stigma, getting psychedelics out of your friends’ basements and into clinics. Medical legalization could be the gateway to a broader legalization for use by healthy people, but the word “recreational” doesn’t fit. They aren’t fun.

Although it is normally only acceptable to test the effects of drugs on the unwell for medicinal purposes, a 2006 JHU study looked into the effects of two to three doses of psilocybin on 36 healthy, college-educated adults. A third of participants described the experience as the most spiritually significant one of their lives. 12 percent said it was the most personally meaningful event of their lives, and over half placed it in their top five. They reported positive changes in their lives for many months afterwards, changes that were corroborated by community observers. These included significant positive changes in mood, behavior, altruism and meaning.

Psychedelics have been shown to reliably produce profound, life-altering experiences that can increase quality of life. They temporarily alter or obliterate our sense of self, free us from usual thought patterns and allow us to see past the everyday to grasp what’s truly important. Legalization for the betterment of healthy people is perhaps a logical end goal, not to mention an altruistic and loving one.

Many people dismiss psychedelic experiences and perhaps even the research on them, believing that users are fooled by a “drug experience” that isn’t “real.”

“Real,” like all words, is ambiguous. Countless psychological studies show that sober people do not experience “reality,” but rather a version bent by sensory illusions, selective attention, biases and expectations. Do we have any authority to make claims about the ultimate nature of reality from this falsifiable perspective of consciousness?

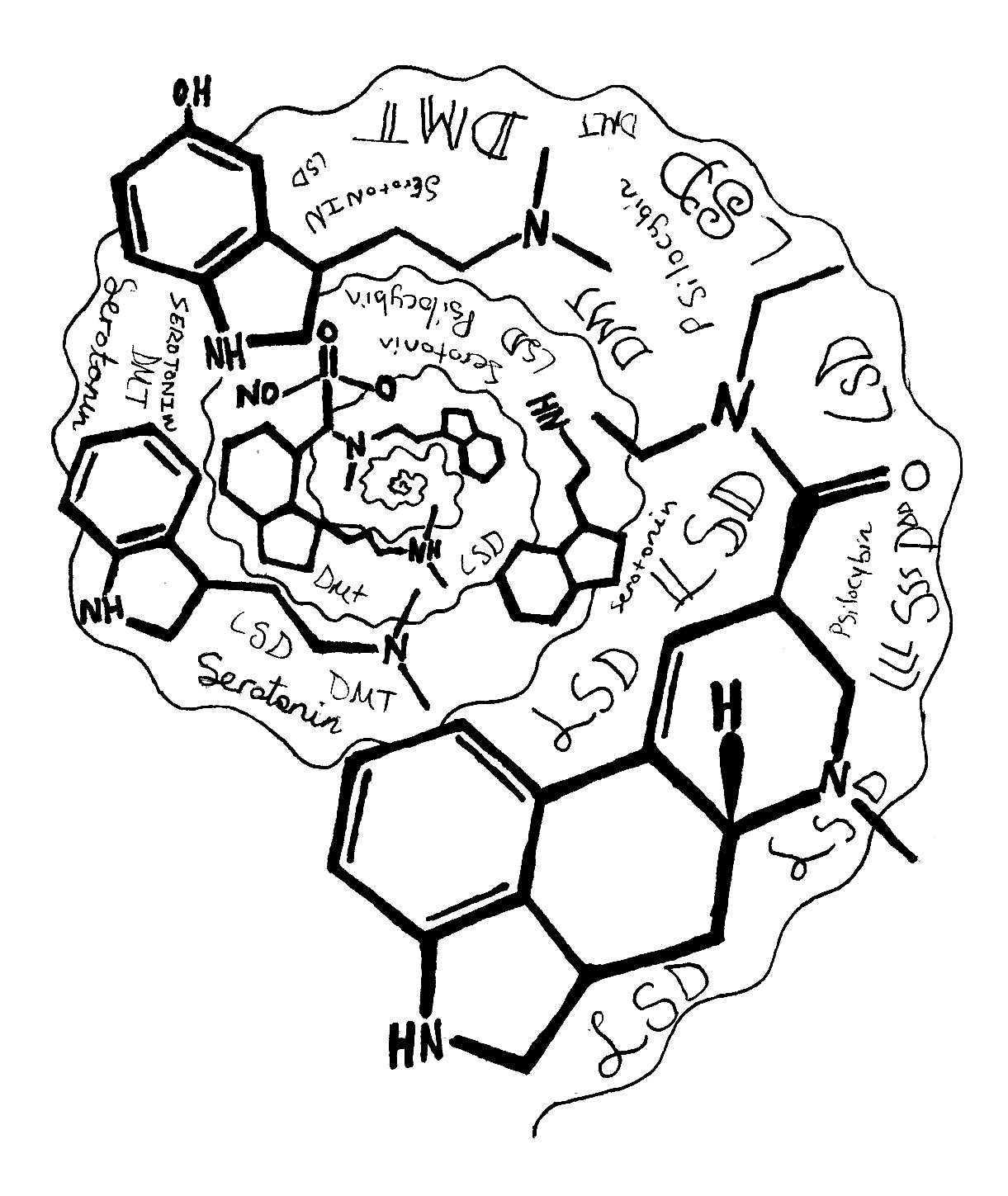

Everything within your conscious experience is made from the chemical soup of your brain. Like the endogenous chemical serotonin, many psychedelic chemicals take effect by binding to the same receptors. All experiences are made of chemicals. Experiences you attribute to things outside you are within you. Your reality is a controlled hallucination.

All experiences are real though, including psychedelic ones, because they happen. And what standard of reality is there other than direct experience? None at all. Isn’t that beautiful?

Drew Humphreys is a member of the class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: