Obama accepts prize in honor of Paul Douglas, class of 1913

September 20, 2018

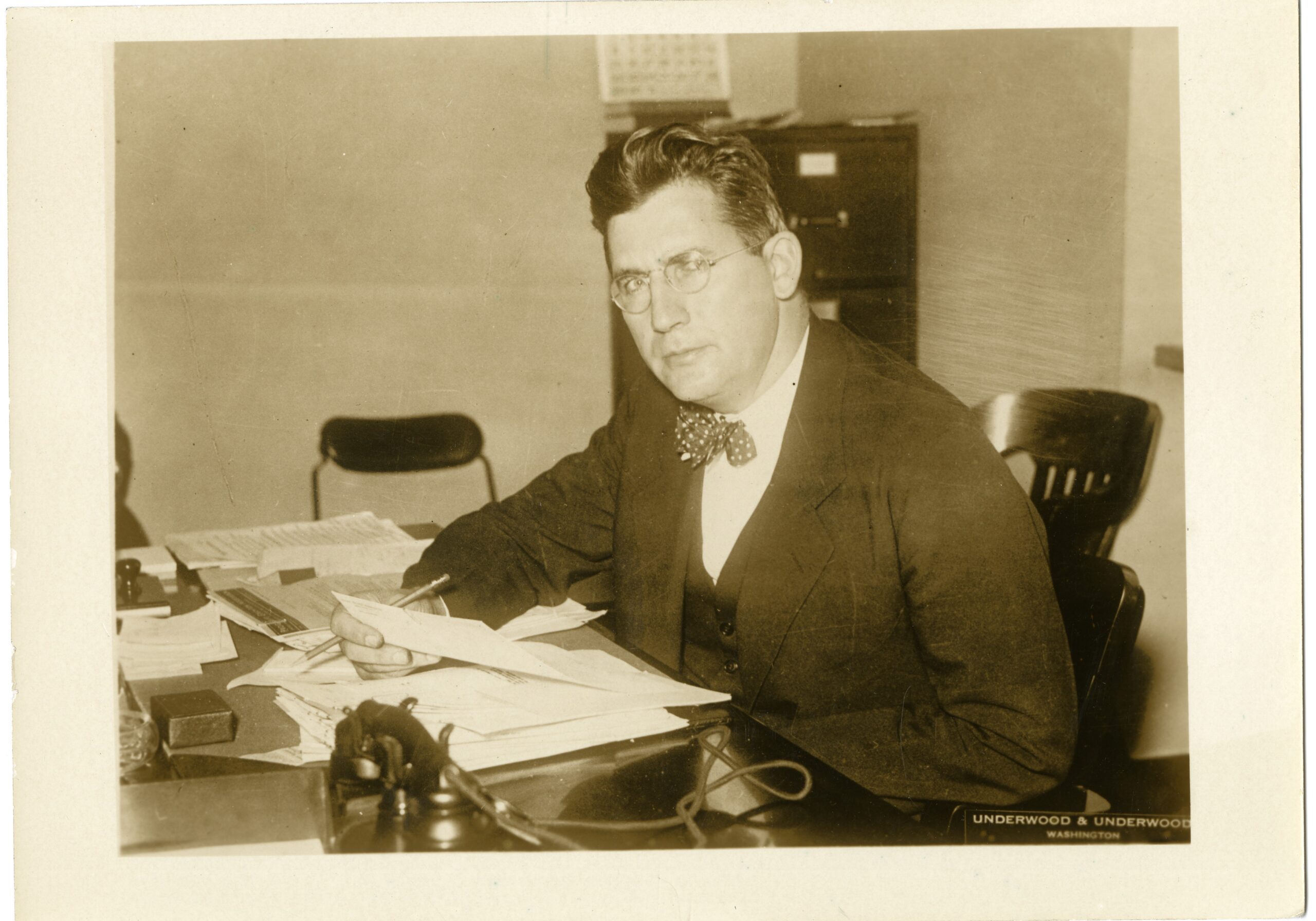

Courtesy of George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library

Courtesy of George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College LibraryWhen President Barack Obama emerged from his post-tenure elusiveness to give a speech at the University of Illinois, he was accepting an award named after a Bowdoin alum. The Paul H. Douglas Award for Ethics in Government is named in recognition of a distinguished economist who graduated from the College in 1913.

Following his graduation, Douglas went on to live a distinguished life in the field of economics as well as in government and the military. While Bowdoin students know about Joshua Chamberlain, far fewer know about the man the New York Times once called “the standard by which other men … live their life.” This is probably because, as Dean of Student Affairs Tim Foster put it, “[Douglas] preferred to have others take credit for his successes.”

Jim Paul, assistant director of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois System, said the Ethics in Government Award is one way to maintain the economist’s political legacy.

“We try to choose people with a solid and consistent record of working with opponents to attain a greater good,” Paul said.

Douglas spoke in a 1951 Bowdoin commencement address about the importance of what he called “civic courage,” explaining that he believed everyone had within them the capacity to improve the lives of others.

Born in Massachusetts in 1892, Douglas played football and studied economics at Bowdoin, before going on to earn his masters and Ph.D from Columbia University. He had an impressive career as an academic, teaching economics at the University of Illinois (hence their stewardship over his award), Reed College, the University of Washington and the University of Chicago. Alongside felow economist Charlie Cobb, he developed the Cobb-Douglas production function—a staple model still taught in introductory economics courses.

While many economists concern themselves primarily with the theoretical side of the discipline, Douglas was also interested in whether it could be managed more ethically, putting great effort into studying how to increase labor wages. Professor of Economics Daniel Stone speaks highly of Douglas’ character.

“He was not only as good a guy as an economist can be, but as good a guy as anyone can be,” Stone said.

Douglas’s drive for direct action drew him to politics in a 1935 run for mayor of Chicago. The campaign was unsuccessful, but only marked the beginning of his political career. Because of Douglas’s strong convictions, he was relatively untethered from partisan politics, shifting among the Democrats, Republicans and Socialists through his tenure. He worked as advisor to both the Republican Governor of Pennsylvania Gifford Pinchot, as well as to the Democratic Governor of New York, future president Franklin Roosevelt.

Douglas was driven to another kind of action during WWII, when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. He was a strange candidate for war, as he was 50 years old and a Quaker—a traditionally pacifist sect of Christianity. Douglas received a Purple Heart and an honorable discharge after a serious arm injury at the battle of Okinawa.

In 1947, he was elected president of the American Economics Association. This puts him in the company of names like Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke, the last two Federal Reserve chairs. Douglas’ first foray in national politics came in 1948, when he ran against the isolationist incumbent senator from Illinois, a campaign which ended in victory.

Douglas laid out very early on in his political career that ethics were of the utmost importance to him, and he convinced his peers of this enough to earn the nickname “conscience of the Senate.”

“Nobody could question his sincerity because he was really willing to make the sacrifices,” said Stone.

As a senator, Douglas used his economic know-how to push progressive ideas like tax reform and the Truth in Lending Act, which held lending institutions to higher standards of transparency. During the 1960s, he supported the Civil Rights Act and was instrumental in formulating the Voting Rights Act. He made additional political contributions towards housing reform, education, workers’ rights, Medicare and environmental conservation.

Senator Paul Douglas’ career lasted until 1966 when he failed to gain reelection. He spent the last ten years of his life working on campaigns and writing books.

Stone believes more economists should follow Douglas’s example.

“Economists should be mindful and make an effort to think how we can improve society,” Stone said.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: