The monster we know: the need for call-out culture

April 13, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

I spent the majority of my freshman year at the center of a complex and painful Title IX case. What is important about this case is not any salacious detail, but rather the immersive introduction it allowed me to the brutality many members of the Bowdoin community exhibit when their friend or teammate is accused of and found responsible for sexual violence. Through the intervening years, I have had to work through not only the trauma itself, but the secondary trauma caused by a campaign of disbelief, retribution and general misogyny. I will never forget what it felt like to realize how quickly Bowdoin students will excuse violence and hate survivors, as long as they know the accused. After the fallout of my Title IX case, the day that the perpetrator was moved out of his first-year dorm, one of his friends said to me that I had “only seen one side” of that man. Maybe, this guy said, had I known him as the charming friend that he was to some, I would have let what he did slide. I did know that version of him. His charm was what convinced so many people that he could never have done what he did.

So, then, you can imagine the interest with which I read Osa Fasehun’s most recent column, in which he suggested instituting “a panel of students who nominate themselves to handle sexual misconduct reports from named or anonymous students” in place of “call-out culture,” a troubling trend that he sees afoot. I will not devote extensive space to refuting the particulars of Osa’s suggestion. To do so would imply it has particulars, as opposed to simply being what, I must admit, I suspect it to be: another attempt to shield perpetrators of sexual violence from publicity and consequences. I can only hope that Osa is legitimately mistaken about the prevalence of false reports and that he genuinely views false accusations to be a threat that exists at a rate far more threatening than the rate of sexual violence. Otherwise, he would see that creating yet another extrajudicial “solution” will neither lower the incidence of sexual violence on campus nor lead to effective punishment of assailants.

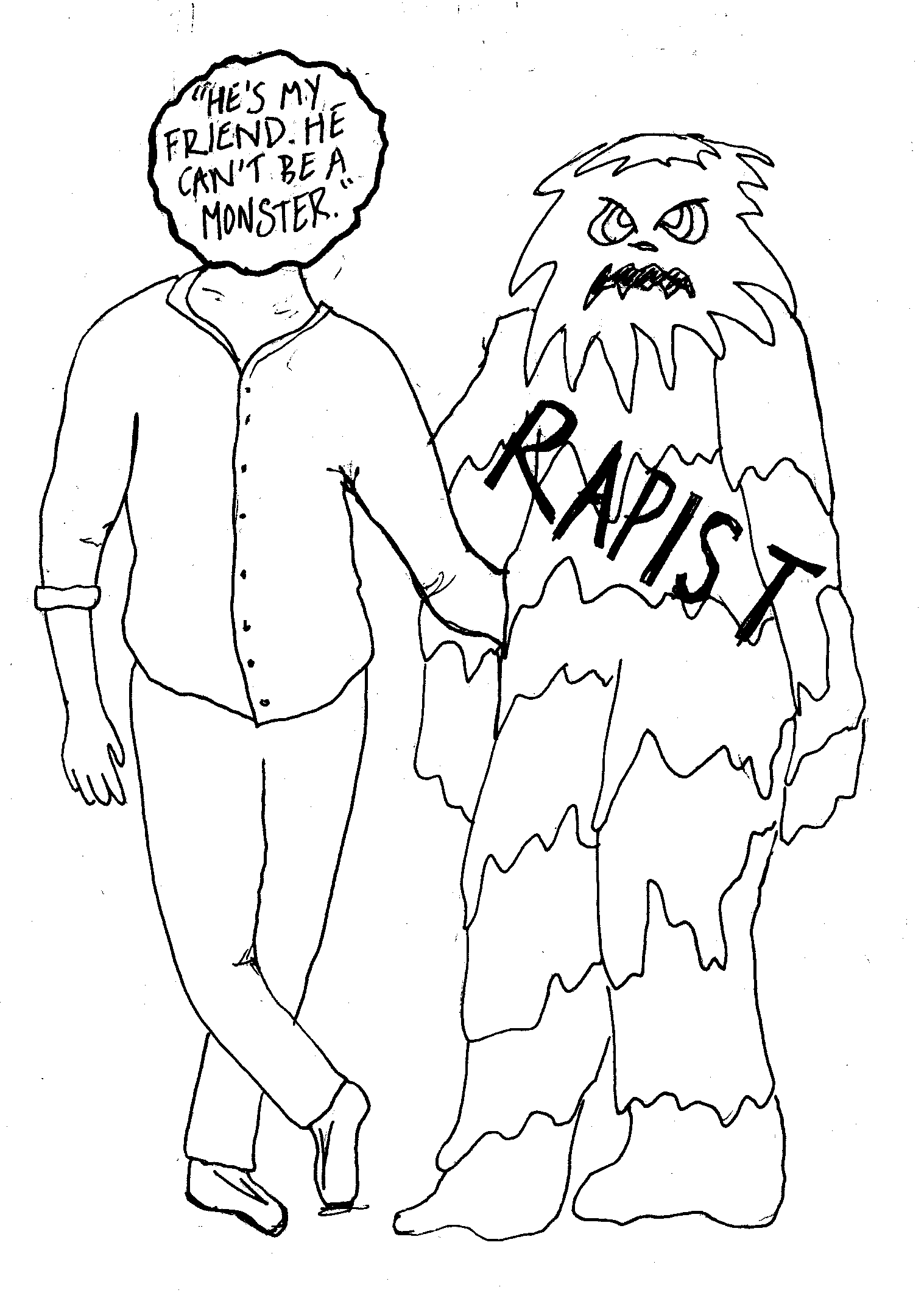

I would instead prefer to address Osa’s inherent assumption that “the pulse” of Bowdoin’s social culture is in any way opposed to sexual violence—that our “recognized moral code” resists it. This would be exciting news—to hear that Bowdoin’s social values have changed so significantly in the three years since my own experience. It seems likely, however, that things have largely stayed the same: everyone is opposed to sexual violence on principle, but when faced with accusations against a peer, they abandon principle without even realizing what they’ve left behind. It’s not that they think rape is okay in this situation or that, in learning that their friend assaults others, they begin to endorse it. Rather, they become willing to admit complexity when horrible acts are committed by someone they know. Their friend is not a monster, but that act is monstrous. The conclusion follows logically: if committing rape implies that someone is a monster, then someone not being a monster means that they could not have raped.

Osa writes, in perhaps the most galling part of this entire column, that “reminders about our pledges to Bowdoin’s social code and basic human decency could instill in accused aggressors a serious commitment to the community. Some students would appreciate this tactic if they were behaving poorly out of ignorance.” I don’t seem to understand the mechanism at work here, since sitting a rapist down after the fact and giving them a talking-to is an inefficient basis for a functional system, but I do understand the worldview that would suggest it. Rapists do not rape because they forget that rape is bad. The acts perpetrators commit are inexcusable, but the face they wear is familiar. This is the tension we must learn to live with in order to achieve actual sexual justice on campuses and in society. We must handle, too, the tension between individual agency—since rapists and predators choose what they do—and structural injustice, as cultural moves and power imbalances promote and tacitly endorse certain behaviors. I cannot offer any concrete solutions to these problems in this space or, perhaps, at all. What I can offer, however, is a framework in which to better understand these tensions.

Humans are particular creatures. We resist the punishment of those we know and those we love because we understand, upon knowing them, their complexity. It is far more difficult to see people we know as truly good or truly evil. This is, I think, at the root of our legal system. Trial by a jury of one’s peers introduces mercy to the judicial system. It is easy to draft and enforce a draconian legal system when there is no face attached to those it punishes. But when one is tried by one’s peers, the ruling comes down from those who can see themselves easily sitting at the defendant’s table. This is not to say, of course, that every case currently tried in the American court system places defendants in front of a jury of their peers, nor that all juries are appropriately merciful. The role that juries serve in an idealized court system, however, is to place human mercy and grace on one side of justice’s scale, counterbalanced by the force of inflexible law.

What I fear is that everyone is particular at Bowdoin. When a case is tried in the court of public opinion, even without appearance in front of any board, the problem is not that an innocent accused may end up without recourse. This hypothetical scenario exists primarily in the fever dreams of those who distrust survivors. Indeed, reliance on Bowdoin public opinion makes it all too easy to allow fellow-feeling for the accused to overwhelm any sympathy one might feel towards the victim. The moment of violence exists in painful privacy; the moment of accusation occurs with glaring publicity. The vague type of harm that accusation imitates—the potential for punishment it entails—overwhelms its viewers, obscuring the original and fundamental act committed by the perpetrator. If our mechanism for resolving cases of sexual violence is this proposed jury of our peers, then very few survivors will find justice, since very few students will distrust their peers enough to deliver it. Osa is right that “it may be anxiety-inducing to trust fellow students to judge fairly,” and he is also right that “one of the reasons for this fear is that deep down, we are aware that sexism is deeply entrenched in American life.” I hope, then, he can see why it is not only anxiety-inducing to trust fellow students, but that it would be deeply stupid to base a legal system on that trust, which I have no reason to offer.

To understand our resistance to the punishment of those for whom we have even a bit of fellow-feeling is then to arrive immediately and without enormous difficulty at the need for call-out culture. Osa is again right when he says that “calling-out is a last resort, a sign of urgency.” We’re there. We are in crisis. I appreciate and respect Osa’s final call for men to speak to their friends; it is admirable that he recognizes the role that such discussion can play, although, of course, not every act of sexual violence on Bowdoin’s campus is committed by men against women. We have been unable to productively prevent sexual violence on campus because of the ease with which perpetrators are able to distance “genuine bad guys” from their own nuanced selves. Only an evil person would rape someone, says a Bowdoin student just like you and me, who can easily withstand the cognitive dissonance then caused when he takes someone home who is too drunk to consent. I worry, however, that this cognitive dissonance extends beyond the perpetrators themselves and renders Bowdoin’s community unable to legitimately respond to the sexual violence that occurs here. It is only by seeing the sweeping extent of the problem of sexual violence at Bowdoin that we can begin to reckon with our own complicity in it. This is why call-out culture works.

Helen Ross is a member of the Class of 2018.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Thank you very much for your brave article. Please know that many of us alumni support efforts to effectively eliminate rapes at Bowdoin.