The influence of hurricanes on presidential politics

September 15, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

In today’s world, natural disasters are inherently political. They drastically disrupt and change the lives of countless Americans, and it is often the government’s job to provide support and aid in response. This responsibility falls squarely into my choice definition of politics: “Who gets what, where and why.”

Because the need for government action is often so sudden, and so concentrated, there is relatively little room for partisan squabbling in the wake of a catastrophic event. Natural disasters give politicians in Washington, D.C. the rare chance to appear authentically and tangibly human, sidelining ideological divides and coming together in temporary harmony. There are certainly exceptions to this trend, as we saw in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, but as a general rule-of-thumb it’s the responsibility of politicians across the country, and across all party lines, to share in a common empathy when addressing regional crises. No matter the catastrophe, no matter the politician, there’s a very good chance that subsequent speeches will stress unity and community as essential elements to the rebuilding process. Often, this unity and community is amplified to a national scale.

Because of this, nowhere is the responsibility for heralding such unity stronger than in the office of the president. As the primary statesman and de facto spokesperson for the American people, the president of the United States is expected to be a role model of empathy in the wake of natural disaster. This expectation is certainly rooted in tradition, but it’s also a core component of the presidential job description. As “chief citizen,” the president is expected to represent all of the American people, and feel the pain of every community. If a president fails to show proper empathy in a situation of dire hardship, public perception of their leadership ability can be seriously impacted.

I think most of us would agree that sincerely reaching out to impacted communities sounds like one of the easiest responsibilities of the president—aside from the turkey pardon—but it’s worth exploring some of the more nuanced complexities of a seemingly straightforward approach. Words are meaningless if they aren’t followed by supportive actions, and this is where catastrophe response gets dicey. Through the specific lens of hurricane response, we don’t have to look far for examples of this. All three presidents in my lifetime have dealt with monumental storms: President George W. Bush oversaw the response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, President Barack Obama the response to Hurricane Sandy in 2012, and now President Donald Trump faces a similar challenge in response to Hurricane Harvey and Irma. It is widely acknowledged that Katrina had a negative impact on the Bush presidency, whereas Hurricane Sandy, which occurred a month before President Obama’s reelection, likely bolstered his performance at the polls. In fact, according to the New York Times, only days after Sandy had blown through, national surveys showed Americans overwhelmingly supported Obama’s response to Sandy and that that support had boosted his favorability. Why the difference?

A lot of it has to do with what the president sees as federal responsibility. Effective hurricane response goes far beyond a president’s ability to appear in the impacted area with words of encouragement. Yes, that may show a bare-bones level of empathy, but truly feeling for a community involves being an active player in its reconstruction. In the wake of Katrina, residents of coastal Louisiana waited days (or longer) for a concerted federal response, stranded in flooded homes or crammed into local shelters without power or food. Although President Bush appeared in solidarity with the people of Louisiana, his response made many question the authenticity of that assertion. On the other hand, only mere hours after Sandy had dissipated, the National Guard appeared under President Obama’s authority with supplies and relief for those affected.

People often warn against politicizing a tragedy, but in this case the response to the tragedy is political whether we want it to be or not. The fact of the matter is, effective hurricane response is a prime example of “big government” working. Many Republican lawmakers across the country advocate for privatized or local-government responses because the alternative would be inherently at odds with their worldview. A strong federal response to a natural disaster, supported by taxpayers around the country, is essentially an intensified social safety net, and Republicans know this. Employing the full force of the federal government, as President Obama did in the wake of Sandy, is hard to swallow for any president who expounds upon the merits of small, decentralized government. President Bush’s response was likely inhibited by his administration’s confusion: how do you respond with the required scope while still remaining fundamentally Republican/Conservative?

Now, this is not to say Republican lawmakers are incapable of appropriate response. In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, many Republicans across the country (not you, Senator Cruz) sacrificed “small-government” beliefs for the common good, an inspiring example of true patriotism. Learning from the lessons of Katrina, it became understood in Washington that certain disasters required diversions from a stringent economic worldview.

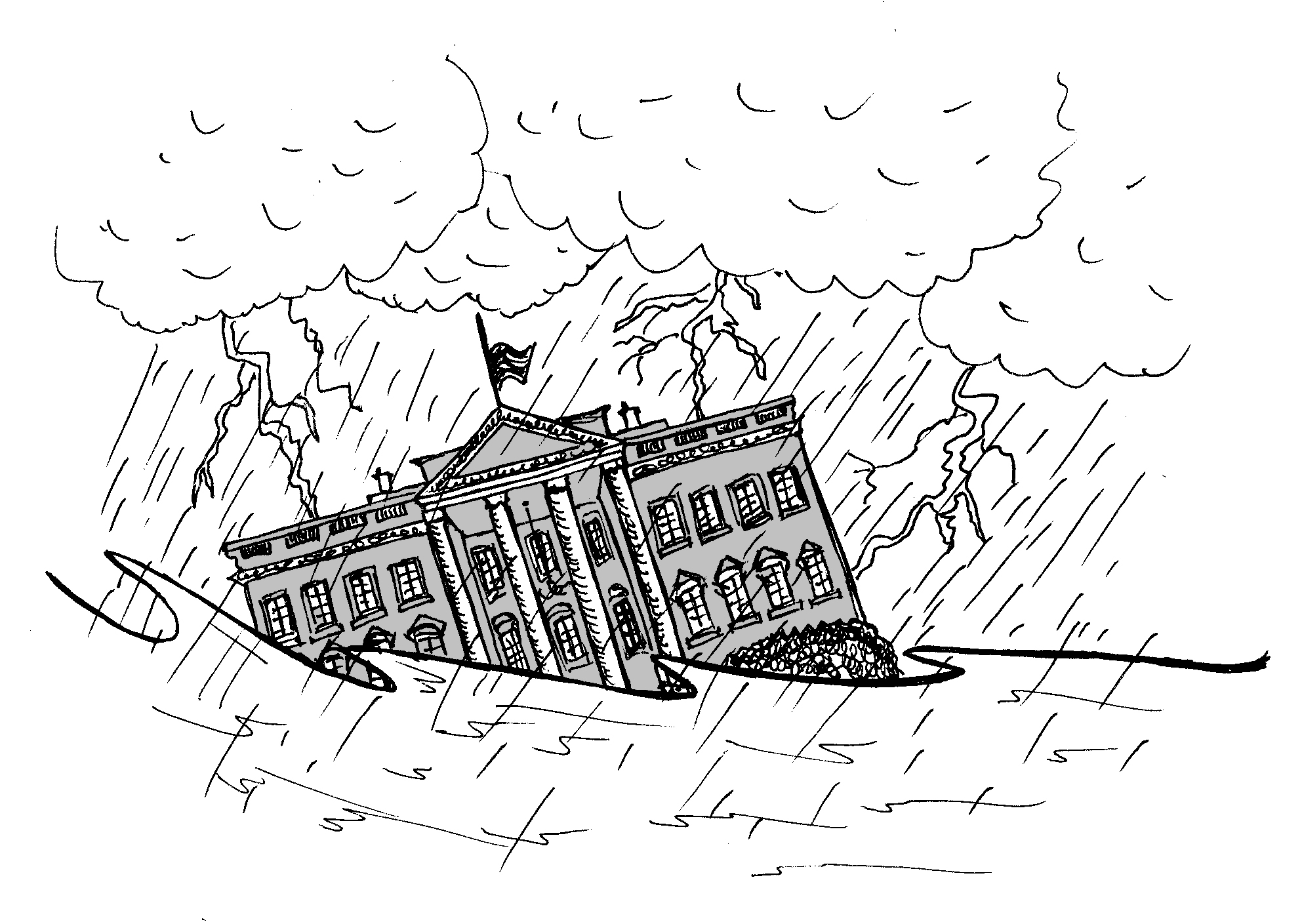

Considering this, watching President Trump’s response to Harvey and Irma will be very interesting. One thing I’m particularly interested in is seeing how he evades the topic of climate change. As the American populace (hopefully) recognizes these frequent, intense storms as a byproduct of man-made global warming, it would befit the responsibility of “chief citizen” to adapt the government’s viewpoint accordingly. However, just as with “big government” disaster response, admitting the seemingly obvious climate change link would starkly contradict the Trump administration’s worldview, and therefore the truly necessary response will undoubtedly be avoided. Any oral empathy President Trump shows and any reconstruction bill he signs will therefore be viewed in the long-run as a woefully inept response to a much larger problem. It could, theoretically, be the ineptitude that finally sinks his administration.

Brendan Murtha is a member of the class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Very well-written, Brendan, and a spot-on analysis. For me, even more interesting than Trump’s response to Harvey and Irma (lackluster and uninspiring at best thus far) will be his supporters’ perception of it.