“Hung Liu: Happy and Gay” opens at BCMA, sparking conversations on Chinese history, time and movement

January 23, 2026

Abigail Hebert

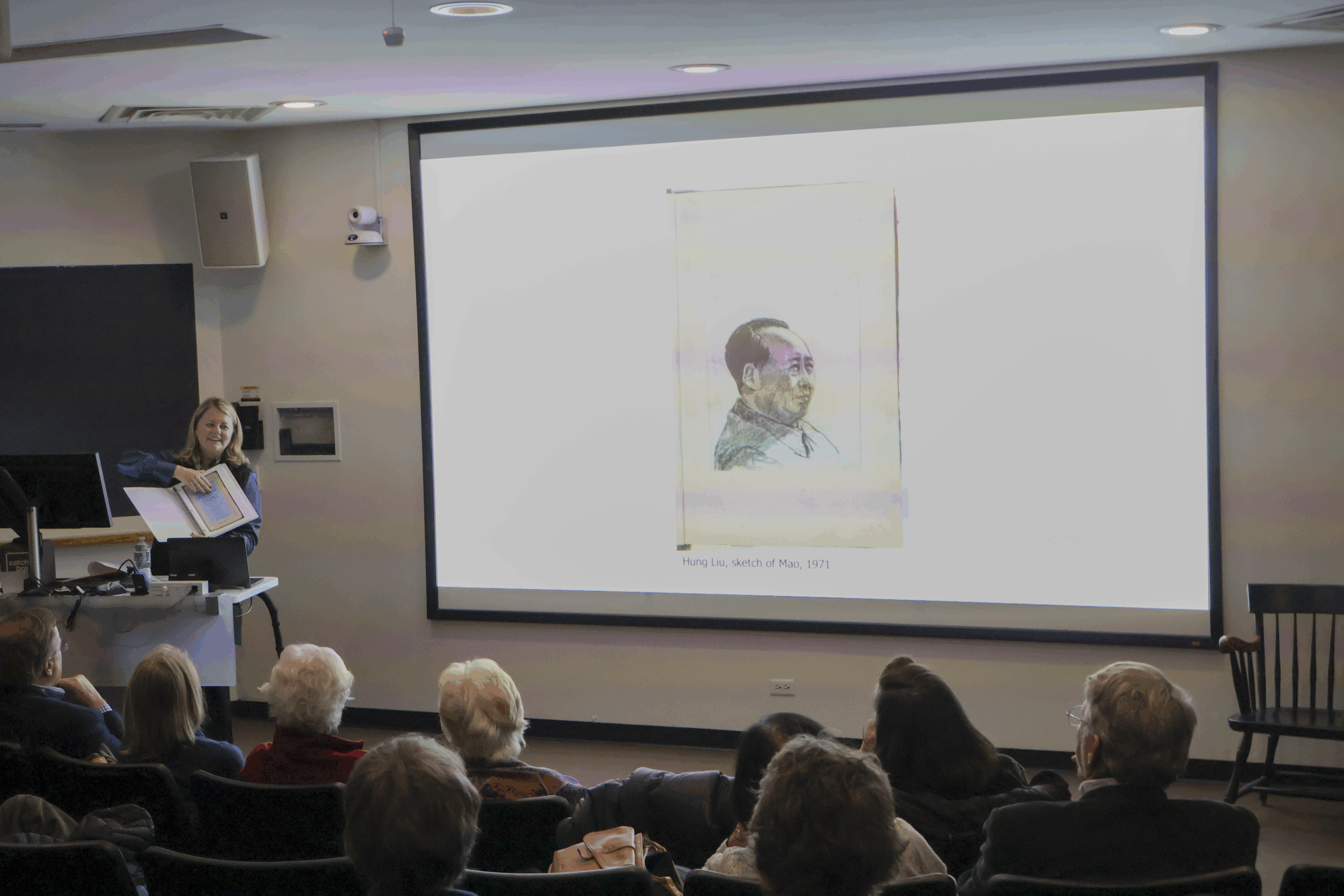

Abigail HebertOn Thursday, Dr. Dorothy Moss joined students, community members and friends and family of Hung Liu in the Visual Arts Center to celebrate the opening of ‘Hung Liu: Happy and Gay’ at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Moss, who is the director of the Hung Liu estate and one of the curators of the exhibition, alongside 12 Georgetown University graduate students, gave a lecture titled “Hung Liu: History is a Verb,” examining Liu’s life, work and legacy.

Hung Liu was born in 1948 in Changchun, China under the leadership of Mao Zedong and immigrated to the United States in 1984 to pursue a degree at the University of California San Diego. Moss explained how Liu’s life shaped her artwork.

“Growing up during the era of Mao Zedong, [Liu] was sent to the countryside outside Beijing in her 20s for proletarian reeducation,” Moss said. “Her experience working on a communal farm for four years during the Cultural Revolution, coupled with her training in the socialist realist style, laid the groundwork for her artistic development.”

One of Liu’s early collections, the Capp Street Project (1988), which included pieces such as “Resident Alien” (1988), explored topics of immigration and tradition, connecting Chinese culture and history with American life.

“Liu’s ongoing adaptation to life in the United States without abandoning her commitment to and love for Chinese art history and literature is evident in her [Capp Street Project],” Moss said. “From the outset, she positioned herself to represent the tension between the promise of San Francisco, the Chinese immigrants and the reality she witnessed, signaling a lifelong commitment to being a voice for the voiceless.”

Time, history and movement were also important themes in Liu’s work, showing in her words, “History is a verb.”

“As [Liu] wrote, ‘This interweaving of images from ancient and modern past continues my interest in a contemporary form of history painting, in which the subjects from one era witness and comment upon those of another, keeping the idea of history open and fluid’,” Moss said. “For Liu, this work of adaptation, of carrying the past into the present without erasing it, became a lifelong project.”

Liu used a variety of techniques and materials in her artwork, such as adding cages or bookshelves to her canvases or incorporating Chinatown souvenirs. Among these various techniques was the use of linseed oil, which Moss explained added a sense of theatricality through its movement.

“She began to collaborate with gravity, pouring linseed oil over the painted surface to create layer drips that reference time and the erosion of memory…, [turning] her paintings into performances, bringing them into real time,” Moss said. “Most of her canvases are still wet, as if they are performing … into this current moment.”

This exhibition, “Hung Liu: Happy and Gay,” features works in which Liu transfers the palm-sized Maoist propaganda cartoons (xiaorenshu) of her childhood onto large canvases, exploring propaganda, education, history and identity. Among the vibrant colors and clear lines, it is notable that several paintings share a common element: a circle, painted somewhere on the canvas. Moss reflected on the significance of the circle in Liu’s works.

“I think about the circle as a beginning and an ending, and the contexts are constantly changing. New meaning is coming into these works, depending on how and where they’re seen. Students are bringing and adding meaning. I do believe that she left an open-ended narrative so that there is no end or beginning,” Moss said.

Sabrina Kearney ’26, who decided to major in art history after seeing Liu’s work in 2021, explained why her work was important at this time in history.

“I think that [“history as a verb”] is the correct way to look at history. I think it’s so easy to forget that, in fact, history is a very subjective thing that is written so often by one side, the side that’s in power…. I think it’s important to know that we’re not powerless in this,” Kearney said. “[Liu] questions the dominant history, capital-H-history…. I think the way that her work touches people across all cultures and ages is a testament to the fact that history is a verb, and we actually can do something to change it.”

Moss voiced a similar sentiment.

“[This] exhibition is beautifully installed at the moment when ICE is entering Maine,” Moss said. “I say these things because [Liu] was always conscious of the context that her work was created in and seen in. She was very responsive to those moments where she knew her voice needed to be heard, and it definitely needs to be heard now.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: