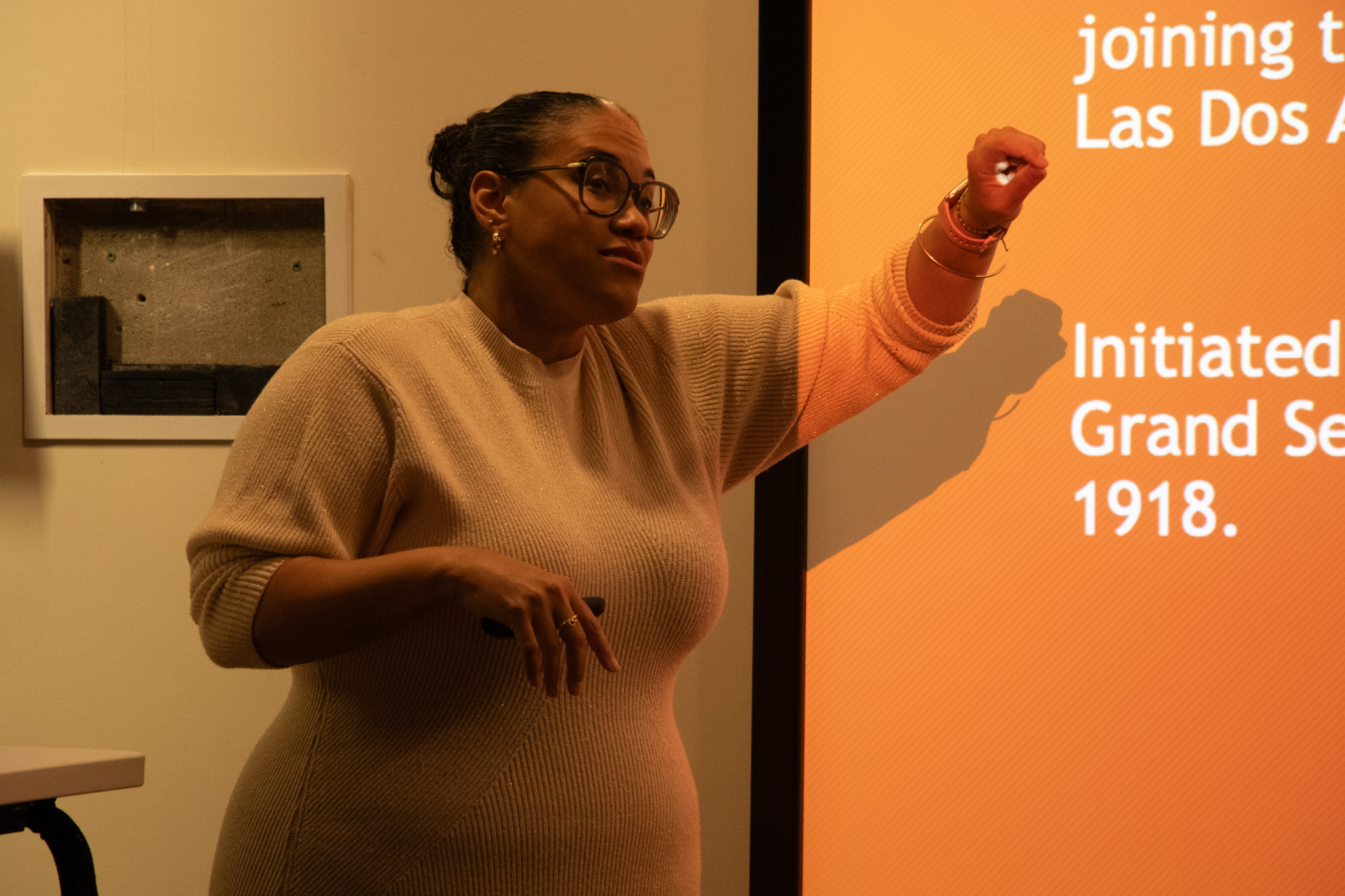

Dr. Vanessa Valdés speaks on the enduring legacy of Arturo Alfonso Schomberg’s archive

October 31, 2025

Isa Cruz

Isa CruzThough we recognize names such as W.E.B. DuBois, Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston in conversations about Black intellectual life, the name Arturo Alfonso Schomburg remains relatively obscure.

Schomburg is the namesake of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, a research library emblematic of his life’s work in documenting global Black history. On Tuesday, writer and scholar Dr. Vanessa K. Valdés shed light on Schomburg’s life and legacy to celebrate the centennial anniversary of the Schomburg Center. The event, held in the Beam Classroom, was hosted by the Latin American, Caribbean and Latinx Studies department, the Africana Studies department and the Library.

Professor of Africana Studies Michele Reid-Vázquez, who organized the event, described it as part of the College’s new “Communities in Focus” series.

“[The series] focuses on U.S. Afro-Latinx and Afro-Latin American communities, especially by sponsoring scholars and artists to talk about the experiences, processes and identities that comprise Afro-Latinidad,” Reid-Vázquez said. “So [Valdés’] work is very much about making this material accessible to the public in ways that you might not get in a classroom.”

Valdés first heard of Schomburg at 19, when she learned of a New York library named after an Afro-Puerto Rican man.

“In many books, he was just a footnote … and I thought, why hasn’t he gotten more attention?” Valdés said. “That’s not a reason to dismiss him. That’s an opportunity for me to do it.”

Two decades later, Valdés took that opportunity, beginning serious research on Schomburg and eventually publishing her book “Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg” in 2017.

Her Black Puerto Rican background and studies in Spanish and Portuguese literature provided her with a unique perspective that resists a narrow view of the Black experience.

“When we use the word Black in the U.S., there’s often a flattening—as if Black equals U.S. But there are all different kinds of Black folks,” Valdés said.

Schomburg’s work and collection embraced the histories of Black people all over the world.

Born in Puerto Rico in 1874 to a Black Virgin Islands-born mother and German Puerto Rican father, Schomburg migrated to New York in 1891. Though most commonly associated with the Harlem Renaissance, Schomburg’s efforts for Black liberation and education began well before this period, Valdés remarked.

Schomburg collected books, pamphlets and art documenting the African diaspora.

“Many archives like to keep in their materials as opposed to having a liberatory ethos, which he does,” Valdés said. “This is about our freedom, our liberation, our emancipation.”

In addition to his collecting work, Schomburg held positions at the American Negro Academy and Fisk University, advocating for the study of Black history in schools and expanding library collections dedicated to Black scholarship.

Today, the Schomburg Center, often described as “where every month is Black History Month,” holds over 11 million books and remains the world’s foremost archive dedicated to global Black history.

“The Schomburg Center continues to do all the things that I say,” Valdés said. “They are open six days a week, they have the Schomburg Center channel on YouTube … they’re very dedicated to accessibility. So it continues to be part of a larger conversation.”

Valdés noted that since her book’s release in 2017, conversations around Schomburg and the Afrolatinidad experience have expanded. Schomburg’s life embodies the idea that Afro-Latinidad and Black identity are not contradictory and affirms the existence of Black history. However, this work is still not done.

“We see the continuing fight about what counts as history and what doesn’t,” Valdés said. “The things that [Schomburg] encountered in the 1880s, we still see today, almost 150 years later, which is astounding,” Valdés said. “And also, you see an equal response.… You have churches who are organizing to support the National Museum of African American History and Culture, because there’s a perceived threat about erasing this history. So how do we maintain our own institutions?”

“There are efforts that are happening that may not make headline news, but people are doing it, and the communities are doing it on a ground level. I think that’s inspiring,” Valdés said.

Valdés encourages students to “stay curious” and not mistake absence in historical records for historical irrelevance.

“There are many books left to be written about Arturo Schomburg,” she said. “I intended for mine to be just the introduction.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: