Paul Jaskot discusses the role of architecture in the Holocaust

November 8, 2024

Abigail Hebert

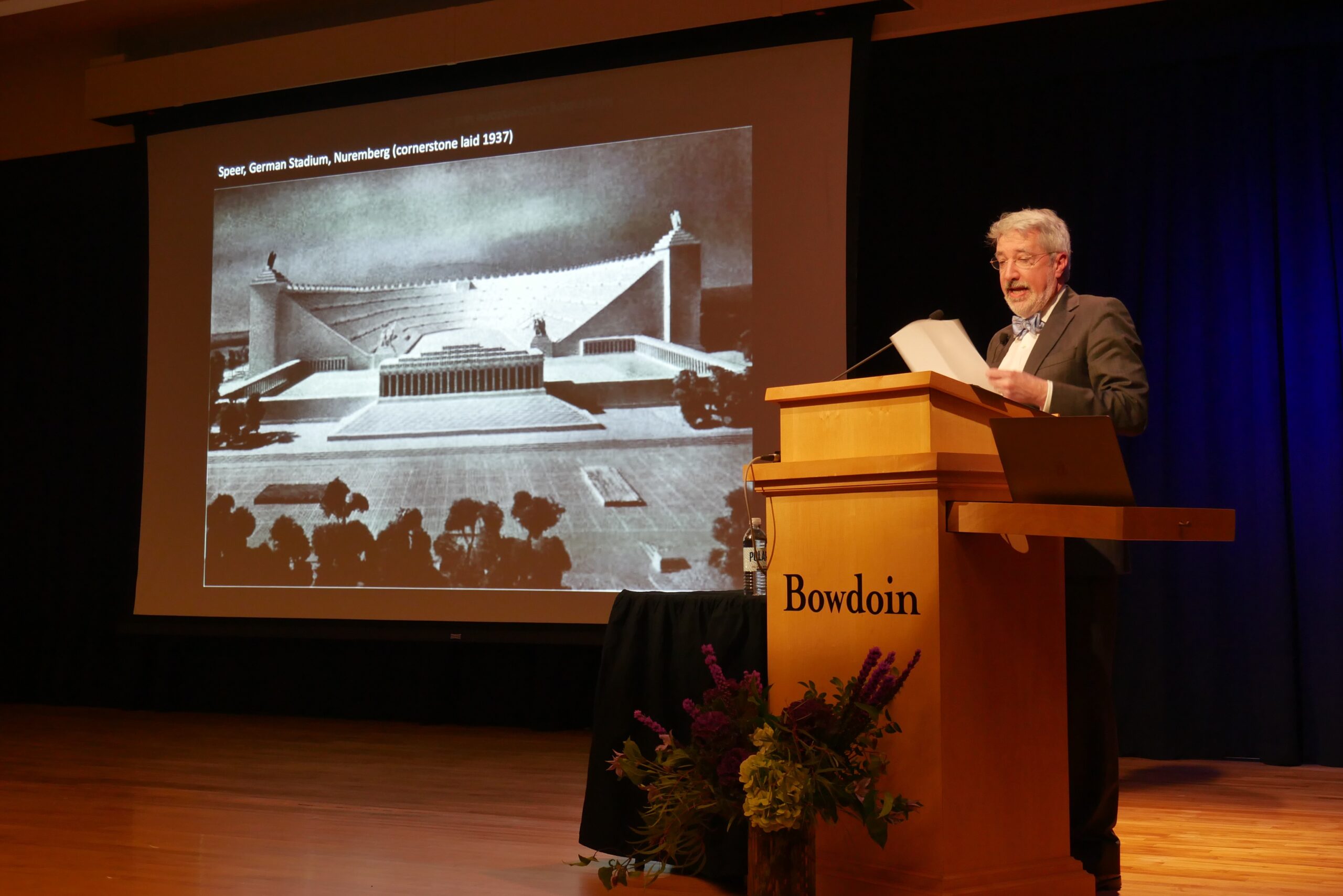

Abigail HebertOn Monday night, Paul Jaskot, professor of art history and German studies at Duke University, delivered the College’s annual Holocaust Education Lecture in Kresge Auditorium. Titled “Architecture and the Holocaust,” Jaskot’s lecture explored the often unseen role architecture played in carrying out the genocide.

Jaskot began by highlighting that, despite the tragedies of the Holocaust, culture was able to survive. Throughout the war and beyond, it remained a form of resistance against Nazi Germany.

“Let us start with the light,” Jaskot said. “It is clear that culture and genocide are opposite terms. Culture is that which is best in human society, that which expresses our dreams and possibilities as well as the uniqueness of our individual and shared group identities. In the face of all the misery that the Holocaust brought, culture survived.”

Yet Jaskot also emphasized the way culture was used for evil. Culture, according to Jaskot, played an important part in Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. Hitler argued that the cultural spheres of society, especially architecture, failed to counteract other failings of a weak German society, which he blamed Jews for in his manifesto “Mein Kampf.”

“Hitler linked architectural quality with the question of political strength,” Jaskot said. “He ended the chapter by stating, not surprisingly, that the unrecognized reason for the weakness of society is the ‘race problem,’ that is to say, the German Jews.”

In the years leading up to World War II, German architecture became increasingly associated with political ambition. Jaskot highlighted as evidence the plans for the German Stadium—a massive stadium where post-war global sporting events would be held.

“The significant and dramatic increase in ambition, evident in the scale, expressed the political expansion of the state. Hitler … made clear his interest in war as a means of extending German territory in the east,” Jaskot said. “The German Stadium … [was intended] to plan for a post-war Germanic future in which the world would look to the Nazi state as the new center.”

Jaskot argued that, beginning in 1938, architecture became increasingly tied to worsening anti-semitic policies in Nazi Germany and eventually the Holocaust’s worst atrocities. For instance, while Jewish property in much of Nazi Germany had to be registered with the SS (the paramilitary organization responsible for much of the genocide), in Berlin, it had to be registered with the General Building Inspector Office.

“This important political alliance with architecture set the stage for fulfilling both the goals of [Nazi architect Albert] Speer’s plan for Berlin, as well as the future concentration and then deportation of the Berlin Jews,” Jaskot said. “One result of this fateful decision would be, for example, that the architectural office organized the deportation of Berlin Jews to ghettoization and murder in the east. That’s who made the lists.”

Attendee Avery Cutler ’26 said the architectural office’s part in the genocide stood out to her.

“It was really interesting to hear about the role that the architectural office had with deportations of Berlin Jews,” Cutler said. “I thought that was a really interesting first example of oppression that we don’t see in history.”

Additionally, Jaskot discussed forced Jewish labor during the Holocaust. Using his digital mapping research, Jaskot explained that the largest category of forced labor for European Jews during the Holocaust was construction. He emphasized that, while the labor sites can be identified, the specific work performed has been erased from history.

“Extending our analysis from pre-war Germany to think about the business of building during the war … focuses our attention on the systemic conditions of war and genocide that were integrated with and expanded by the construction industry, and it also forces us to try to visualize the hidden histories that are part of that particular experience,” Jaskot said.

Senior Lecturer in Environmental Studies Jill Pearlman, who attended the talk, felt that Jaskot’s mapping work effectively conveyed the link between architecture and politics and the profound impact of this connection.

“With his work in digital studies, he was able to show just how vast the scale of the grandiose Nazi building enterprise was, well beyond Germany, and the unfathomable (and until now, invisible) amount of forced hard labor it required,” Pearlman wrote in an email to the Orient.

Jaskot ended his talk with an image of the gates to the Auschwitz concentration camp, which he noted is one of the images most associated with the horrors of the Holocaust. He described how the building, with all its minute details, is itself a product of forced labor.

“We cannot lose sight of the fact that the building represents not only the plans of the perpetrators, but also the actions of victims.… These groups, of course, had wildly different understandings of this grotesque site, but it was here in space, at this scene, that we see the evidence of how individual histories and architectural ambitions converged in 1943,” Jaskot said. “This intersection of architecture and oppression is not unique to Auschwitz but haunts the entire Holocaust.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: