The myth of thinness in distance running

March 3, 2023

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Miles Berry

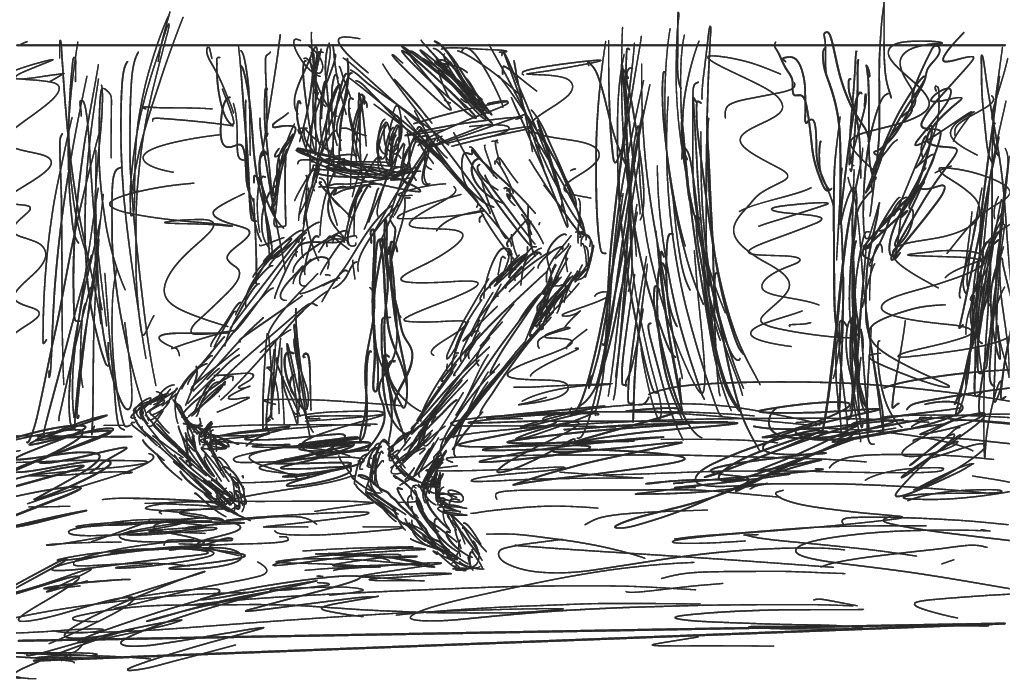

Miles BerryWhen you picture a distance runner, what kind of body do you picture? Maybe you think of someone not too tall, with powerful legs, strong but mostly wiry and thin. Thinness is probably key to the image in your mind’s eye.

In American culture, fitness and wellbeing are far more about appearance than they are about functionality, a burden particularly placed on people who identify or present as women. I know this because in my years of being a competitive distance runner, I’ve met too many women who have been told they “don’t look like a runner” by people (usually men) who have no idea how many miles a week they run, how many difficult hill workouts they’ve crushed, how many tempo workouts they’ve done in the dark, how many races they’ve pushed themselves to their limit. And even if you’ve never been directly told this, it’s easy to internalize that you can’t be a “real runner” if you don’t live up to some arbitrary measure of thinness, an external goalpost that has nothing to do with your ability or your hard work.

And in pursuit of this goalpost, women are encouraged to lose their periods, damage their hormonal health and drive themselves to obsession about nutrition—all to fit into a body standard that doesn’t mean anything. Being thinner than the other girls on the starting line does not matter if your bones are breaking, if you can’t shake the haze of exhaustion that follows your every move, if thoughts about food have filled up your field of vision to the point where you can’t see beyond it.

In Lauren Fleshman’s recent book, “Good for a Girl,” which details her years navigating the toxicity of running culture and expectations as a pro woman runner, she breaks down the science of puberty and women’s sport performance. Many girls in sports are taught to fear puberty and the changes that come with it as they enter high school and into college, terrified by the dreaded performance plateau. But in reality, puberty only makes us stronger, faster and more resilient, and college athletics are a system designed to optimize the performance of male bodies—women’s performances don’t peak until well after their college years. Yet there are still coaches and programs around the country that teach athletes to fight their bodies, to distrust them, to put more stock into their “race weight” than their training. Only three years ago, distance runners on the women’s team at Wesleyan University, part of the NESCAC athletic conference, came forward about a team culture that enabled eating disorders, endless injuries and emotional damage, all, supposedly, in the name of improving performance, but really, in the name of getting athletes to look at certain way.

If you’re not a competitive distance runner, you might wonder what this has to do with you. And truthfully, it is a problem very specific to distance running culture—but at the same time, the implications extend far beyond it. It raises questions of how we value women’s bodies, how we prize aesthetics over all else. It’s deeply tied into women’s sports in general, how athletes who compete for women’s teams are expected to succeed and thrive in a culture that seems to only celebrate and value the success of men’s athletics. And finally, this is a deeper symptom of disordered eating and diet culture in American society—a mindset so pervasive and brainwashing, it has convinced scores of athletes that thinness is worth the cost of everything else, from your performance to your long-term health and happiness.

During this National Eating Disorder Awareness Week in particular, it’s vital that we hold ourselves and others accountable to dismantling beliefs that falsely link body size to ability, health and morality. We must recognize the institutions that profit directly from causing us to hate what we look like, and, as hard as it may be, we have to push back against them. It’s our responsibility to create a better culture, one where athletes feel empowered to compete and succeed in sport, with no caveats about body size attached. We should be celebrating the power, capabilities and resilience of our bodies, rather than their appearances.

Jiahn Son is a member of the Class of 2025.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: