Storyteller

February 17, 2023

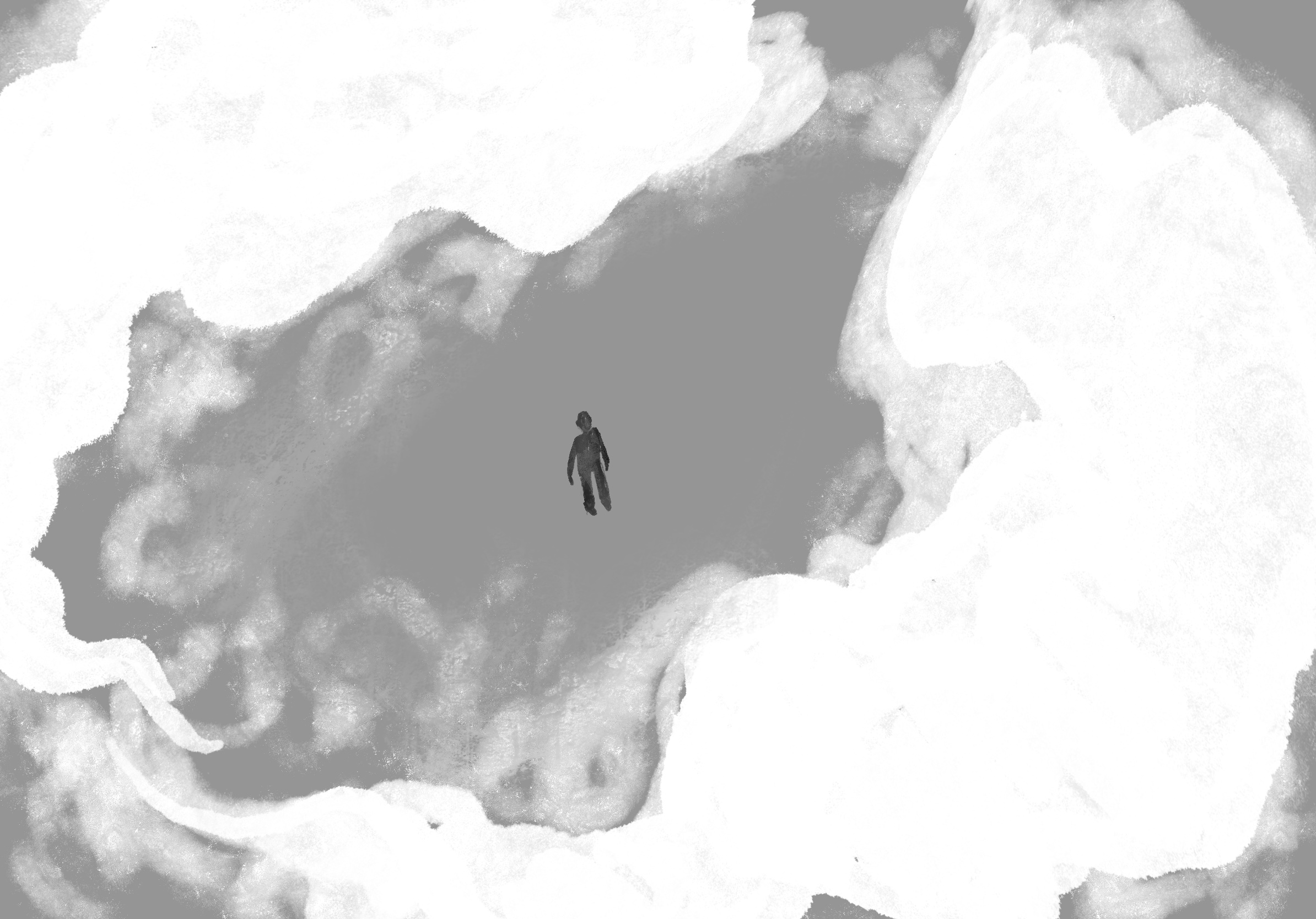

“Nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.” – Walter Benjamin

Endless fields, meadows and rolling hills stretch towards the horizon, where the earth and sky meet, have always met, will forever meet—except when viewed from the forest floor. Sealed off from the sun, giants tower below the canopy, their boles, limbs, twigs and leaves featured among the forest architecture like ancient monuments. The Atlantic carries out its inexorable barrage against the land, crashing against the sand and, where there is none, colliding with high walled rocky promontories in explosions of sound and spray. Offshore, at the tip of a peninsula stretching a little ways into the water, a white lighthouse stands, stalwart, and it is easy to imagine its interminable spotlight shining through an impossibly long, dark and stormy night.

I survey the Maine landscape, and it seems as though all the greens and blues, tones and textures transcend mundane beauty, reaching towards the sublime—or an ineffable sense of greatness. But what is it about the Maine landscape, or the so-called natural world in general, that moves us so?

Since the late 19th century, city-dwellers tired of rapid change at home have flocked to rural areas of Maine, Vermont and New Hampshire seeking refuge in nature. Parts of the countryside that had resisted large-scale industrialization and urbanization for a number of different reasons—low population, a preference for local industry or remote locations—emerged as quintessential New England getaway destinations. During the 1860s, there was a so-called “rediscovery of the Maine landscape,” which popularized the “gospel of rest” and solidified the state’s character as Vacationland; mostly elites, but also a growing number workers from lower socioeconomic standings escaped the bustle of their daily lives by receding into the countryside.

In tandem with transcendental poetry, a burgeoning tourist industry helped the rural landscape assume its own sort of mythology. It was a bulwark of continuity, providing vacationers reprieve from the uncertainty associated with a life constantly in motion, as a result of the industrialization, optimization or urbanization efforts that capital demanded. Although it was in resort owners’ best interests to conjure romantic images of the countryside as a simple, stagnant, place out of time, the symbolic weight of the New England landscape cannot be chalked up solely to some grand marketing scheme.

What is most compelling about this image of nature—commonly understood as separate or outside of the realm of human civilization—is the quality of timelessness we lend it. Certainly, waterfalls and wildflowers are beautiful, but beauty is merely a byproduct of this veneration for the timeless splendor of the natural world; we idolize nature as an other, and more importantly, as of-another-time. As a result, we are awe-inspired by the mother tree that outlives us by hundreds or thousands of years, by the way time turns water into a blade capable of carving through miles and miles of stone, by the repetition, reminiscent of eternity, of lifecycles embedded in soils and dependent on seasons, by fungi that do elude natural death and species-hood altogether. The time of the earth and the nonhuman, especially non-animal, is altogether unfathomable, irreconcilable to the modern human, who is beleaguered by the time of modernity—characterized by rapid change, empty, homogenous, devoid of unifying meaning.

However, changing landscapes confront us and we are forced to recognize that the environment is certainly coeval with us, for it responds to our actions in its own ways; clear cut stands along highways, polluted oceans and smoggy skies have certainly fallen victim to the grimy hands of modernity. I do not contend that if we stop imagining the environment as timeless or of-another-time, then it loses its beauty. Rather, we cling to false notions of a monolithic time, the impregnable time of capital, and thus locate its antithesis in what we call the “natural world.” Recognizing other beings as in-time is not only an act of empathy, which is contingent upon recognizing others as selves, but it can also be a radical act of refusal. When we spend and waste, conjure and lose, keep and tell time in our own ways, with other-than-human beings, we have already refused to accept time as it has been dealt. Next, we must use our own hands to remake it.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: