Compulsory essentialism

April 17, 2020

During my first ever Zoom class, my professor delivered a moving speech. She said that this crisis has forced her to define and defend what she believes is the purpose of a Bowdoin education. In her opinion, that purpose is to make us leaders—in our families, in our communities and in the world. That has always been her prerogative, but these unprecedented circumstances tested her commitment to these values unlike ever before.

As students, we are all grappling with the purpose and relevance of our education in this unique moment. With hilariously meme-worthy virtual classes, no letter grades, an array of distractions, complicated personal circumstances crashing around us and a constant barrage of news reminding us that there are much greater things at stake than the sophistication of our Blackboard discussion posts, we are all asking ourselves: what is the point?

As I mull this question over, a quote from Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden” keeps popping into my mind: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life.”

Although a far cry from Thoreau’s romantic transcendentalist experiment, this pandemic has forced us to practice a sort of compulsory essentialism. At the institutional level, our government has deemed certain jobs, services and people “essential” and others “nonessential” in a very revealing show of power, privilege and values.

On an individual level, as we adapt to the mandates of compulsory essentialism, we still retain a share of agency. As students and teachers, employees and employers, parents and children and, most importantly, as human beings, we must answer the questions: what is essential to me? What is my purpose? What truly matters?

How we answer these questions profoundly reflects our values.

In the realm of education, the process of parsing the essential from the nonessential has likewise put our values and purpose to the test. Take, for instance, how Bowdoin responded to this pandemic. As President Rose confirmed in an email, the debate about whether the College would abandon letter grades for the spring semester was a tense ideological spar. Students also hotly debated the issue; my Facebook feed was riddled with hypothetical scenarios comparing two students who want to go to law or medical school and ensuing arguments about which grading system would yield the most equitable outcomes.

Ultimately, the committee on Governance and Faculty Affairs recommended the College adopt the Credit/No Credit system. In their letter, they state the central rationale: “Of paramount importance is equity, and our desire to remove the inevitable pressure and uncertainty on students should they need to decide whether and which courses to take for letter grades. Credit/No Credit signals to students that our concern for their well-being extends beyond the classroom to their mental and physical health.”

This was a resounding statement about our values and purpose as an institution. Of course, consistency matters, and we must evaluate all their actions under pressure and under normal circumstances. For example, I would argue that the decision to move to Credit/No Credit does not square with the College’s perpetual celebration of meritocracy through Sarah and James Bowdoin Day and awarding Latin Honors. Nonetheless, I believe that the College’s overall response to this global crisis positively reflected what we stand for as an institution.

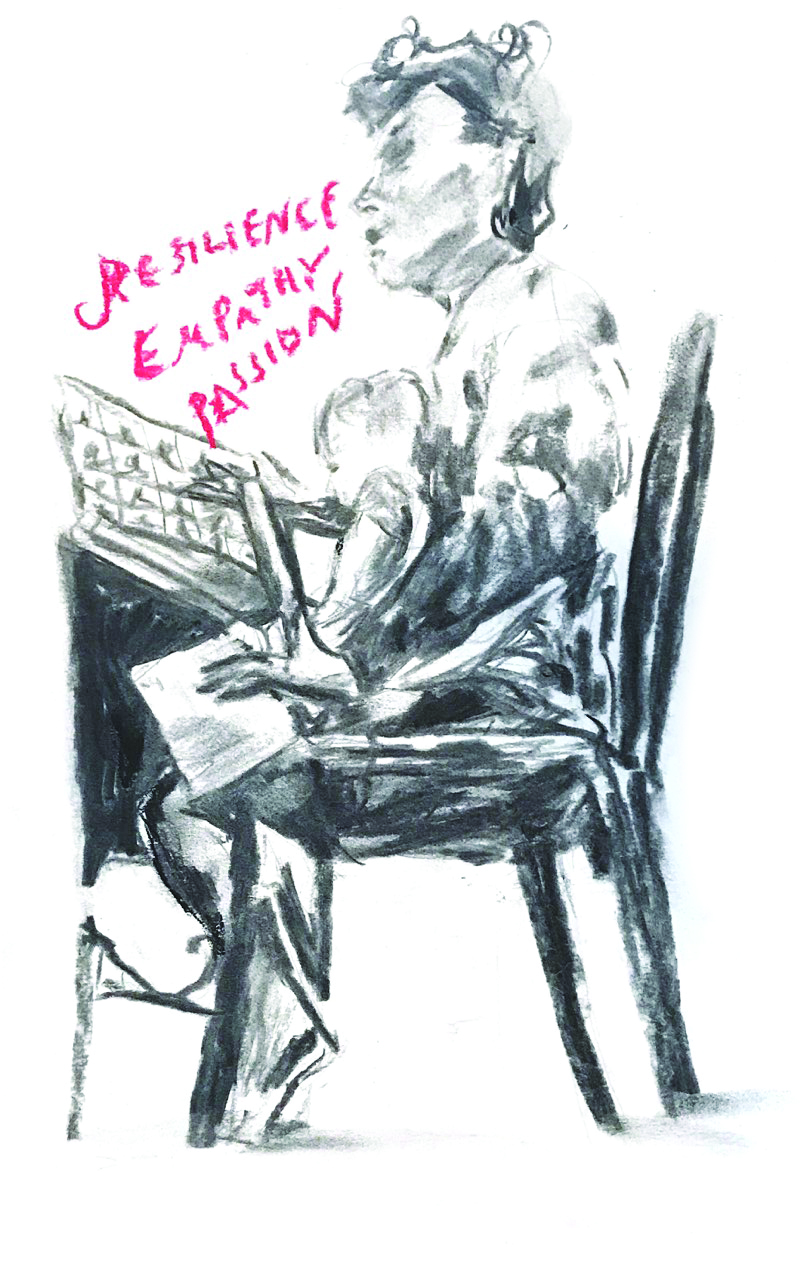

Likewise, all my professors have responded in ways that align with the values of equity and the common good. They have shown incredible resilience, empathy and humaneness. They have made difficult sacrifices by paring down syllabi in order to reduce the curricula to the bare essentials. Without the “stick” of grades, they are rummaging deep into their toolboxes to find strategies to support, nurture and motivate me and my classmates.

Teachers around the world must ask themselves: can I inspire my students by bringing my passion and enthusiasm for the material? Can I make my content and assignments responsive to current events? Can I set aside time to check in with students to find out what is going on in their lives?

On the flipside, our response as students during this crisis has and will continue to reflect our own values and priorities. This crisis has pulled back the veil on our professors to reveal that they, too, are human beings with complicated lives (surprise!). I am faced with this fact as I watch toddlers crawl onto my professors’ laps during class or elderly parents pop onto their screen.

We owe our professors compassion, respect and the benefit of the doubt that they are doing the best they can to help and support us. And, of course, we must show compassion to ourselves and acknowledge our own physical and emotional limitations under these trying circumstances.

The reality is that, on balance, compulsory essentialism sucks. It is nothing like hanging out in a log cabin at Walden Pond. It is painful, messy and devastating. For the less fortunate, it is fatal.

That said, my hope is that when this virus subsides, these lessons will stay with us. We will continue to align our actions with our purpose—in our schools, workplaces, governments, families and communities—and reassess, redefine, defend and appreciate what matters to us. Yes, how we respond in times of crisis says a lot about our values. But, how we respond in the mundane, corona-free moments—however dream-like and far-off they may seem—perhaps says even more.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: