To each according to his contribution…

February 28, 2020

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Sara Caplan

Sara CaplanOur parents told us many clichéd things growing up. Many of these things—if you happen to be American—are intended to convince us that work, more than just being a necessary evil of existing society, is actually valuable and fulfilling. They say that work teaches us the value of a hard-earned dollar. That’s how most people interact with money: almost exclusively as a function of labor performed. Money means survival, so people scaffold their lives around work. We are encouraged to think of money as the points system of modern society, and everything from food to the newest appliance is the subject of constant mental calculus.

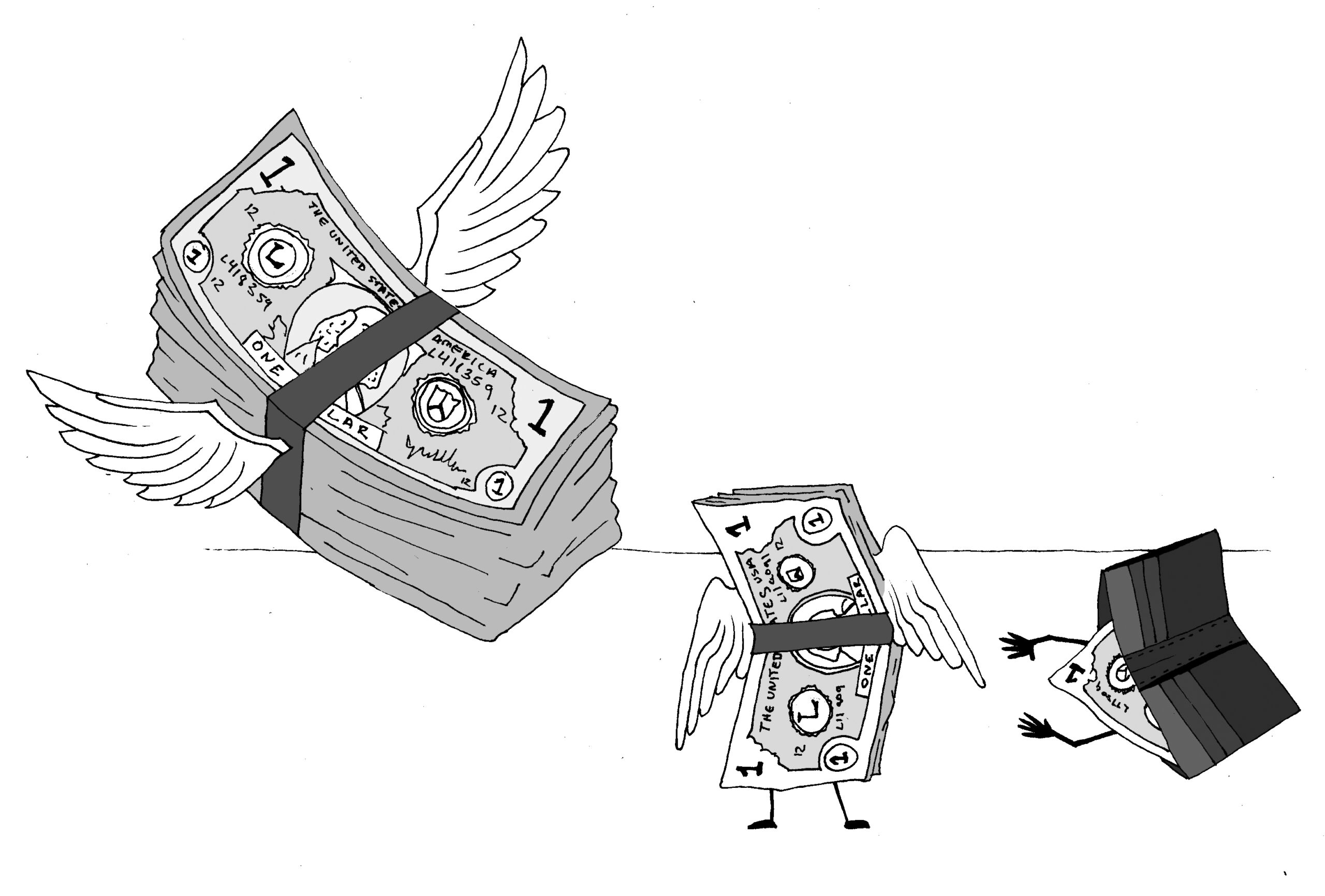

Money, however, has a secret. It’s not just a points system but a commodity in its own right. The mere fact of possessing money can generate more money—labor not required. A very wealthy person could—and many do—live just off the interest produced by their largesse. Investing in the stock market, while requiring slightly more effort and risk, still generates wealth even while the investor is sleeping. Everywhere but Japan, index funds (which track the stock market as a whole) pretty much guarantee exponential returns over a large enough time span.

The problem with money’s double-faceted nature is that, unless you have a lot of it, passive income is generally hard to come by. It is unfair that some people must work to make money while others can attain a fortune without lifting a finger.

How then should we address the issue of money as a commodity? Some argue that we should give up on money altogether. Imagine walking into a store and taking—not buying—everything you need. Imagine working without the expectation of pay. After all, if everything is free, why would you need to? This is the idea of the gift economy, restrained not by money but by a sense of social rights and obligations. Originally, many societies operated this way, albeit on a small scale.

However, money has a lot of advantages, the main being that it is well-equipped to manage desire in a limited world. Although we’d like to imagine that individuals would consume responsibly in a world where everything is free, maybe it’s a good thing that purchasing power is tied to labor. Until total automation is possible (see my column from a few weeks ago), there is necessary work to be done.

Wealth should be tied to work—monetary exchange makes this impossible. A solution to this problem would be to make “un-exchangeable” money. Let’s imagine that you are a worker in this post-money society. You would be paid in vouchers (usable only by you), but just like money, these vouchers would enable you to buy whatever you want. When you go to the grocery store, you hand over your vouchers to the cashier, but instead of putting them in the register, he jots down the value of your purchase and voids your vouchers. In turn, the cashier is paid in his own vouchers that are unrelated to yours. There is no “exchange” taking place.

Communities, in this circumstance, would determine compensation for labor democratically. We could collectively decide to pay professions differently based on talent, experience and social need. In this way, we can incentivize individuals to do the dirty, difficult or tedious jobs that society requires.

Labor vouchers are not a new idea. They were first envisioned by the early utopians of the American Midwest—perhaps because the idea speaks to the American penchant for paid labor. However, if Americans were actually serious about the idea of work being the basis of an ethical society, they would reject the commodification of money and its ability to generate passive income.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

“Collectively decid[ing]” who gets paid how many vouchers will result in the most numerically represented jobs — cashiers, salespeople, fast food preparers — determining that they deserve disproportionately generous pay, while unpopular professions — dentists, lawyers, judges, the bosses who have to manage unskilled and unmotivated workers — are undercompensated. Thus, businesses and the producers of goods become disorganized; rights are wantonly abused (by the powerful new gatekeepers of society, the cashiers) without there being any effective recourse in the courts; teeth start falling out.

There is no incentive to save your vouchers for big purchases because if you die, anything saved is non-transferable and wasted. There is no capital with which to invest in new businesses, so there is no innovation. There is no incentive to work hard, unnoticed hours, or to endure the opportunity cost of pursuing professions that require many years of education — physicians, scientists, engineers — during which time you won’t collect vouchers, knowing that the end rewards are determined not by the invisible hand of the market, but by the idiotic whims of democratic institutions.

This is dystopia, bud.

Karl meet Marx.

Class of 2010 pretty much nails it. What is wrong with money having value in and of itself? Accumulated and then “rented” money, i.e. interest, is just another way to transfer the value of past labor as well as an additional incentive to work. That some manage their lives/finances poorly shouldn’t be a cost transferred to society as a whole. Much like a battery stores energy for future applications saved money allows new enterprises and ideas to be more easily started for the benefit of all. And if there is one truth that never seems to change it’s that those in control of whatever idealized system is put in place will eventually end up with a better deal than the general population. Never fails.