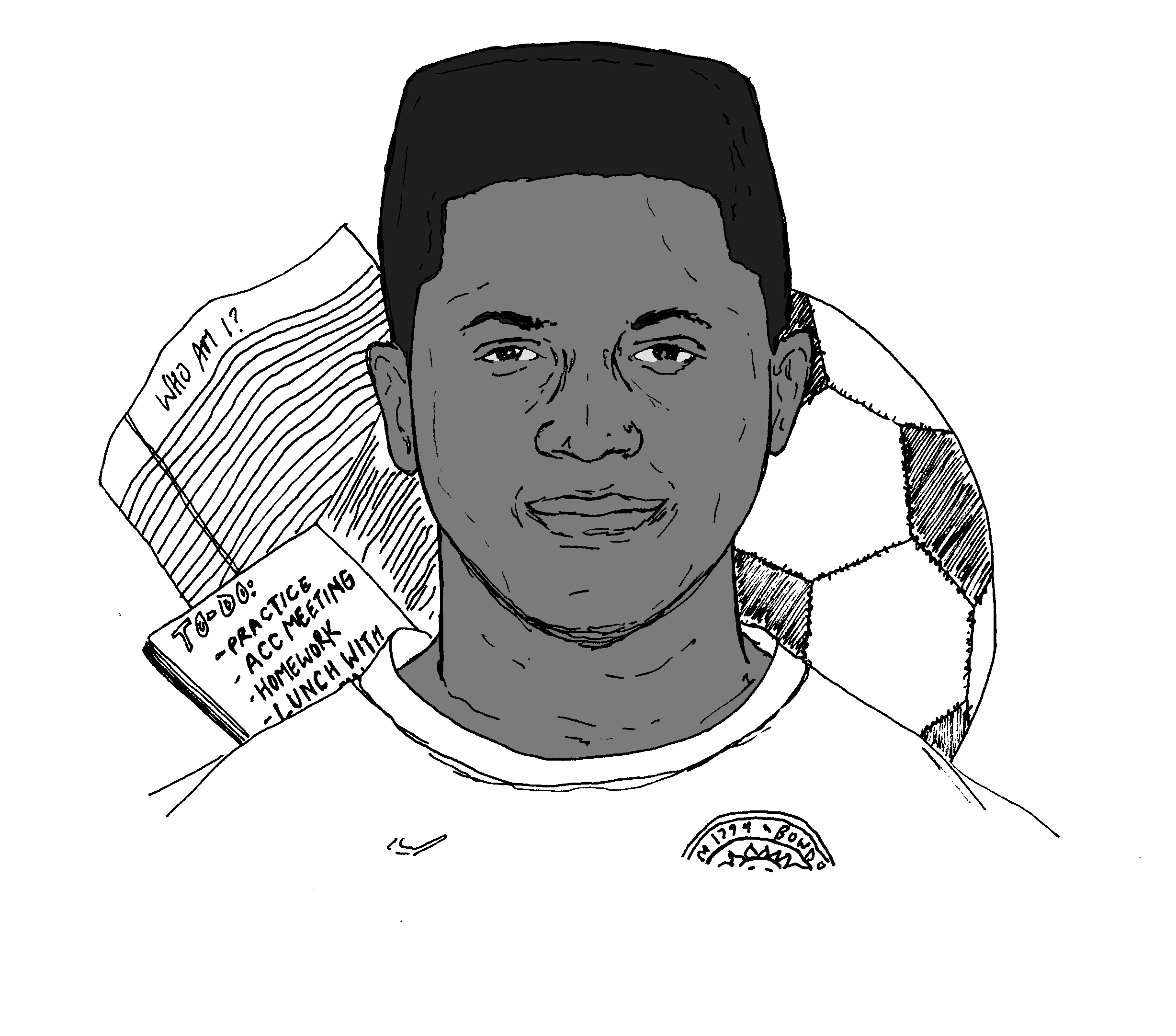

Dual identity: Julius Long ’20 and the black athlete experience

February 7, 2020

Kayla Snyder

Kayla SnyderThroughout the recruiting process, athletes are advised to test their commitment to a school with a crude hypothetical: if you broke your leg, would you stay here? Or worse, what would happen if one day, you hated your sport? What would happen if something inherent to your identity was suddenly stripped from you? Most Bowdoin athletes never have to confront any of these questions. Others meet it face-to-face starting on day one.

Like most Division III athletes, Julius Long ’20 played multiple sports as a kid. But with the pressure to specialize and pursue one sport at the collegiate level, soccer won out over basketball and football.

“I don’t think I was ever really in love with the game of football, as much as I wanted to be,” Long said. “I idealized football, in part, because I saw it as a sport for people who look like me and were from where I’m from, and those examples weren’t exactly there for soccer. I also wasn’t growing as fast as everyone else,” he said, “which is a little bit of a problem if you want to play either of those sports.”

While there were fewer examples of black boys ‘making it’ in soccer, there was clear growth in the game in Southwest Atlanta, where Long is from. In elementary school, Long played for an all-black soccer club, with coaches that dreamt of young black boys playing in college. Even when the club disbanded, Coach E, with whom Long remains in contact, was there to help him see that dream through.

But there would be ups and downs on the road to college soccer. “Getting to Bowdoin, not playing as much as I had hoped, dealing with injuries—I began to feel mentally and physically defeated. But when it was hardest to love soccer, at Bowdoin I think more than anywhere else, I began to understand that the bonds that I had with my teammates were the reason I loved soccer so much—they’re the reason I kept playing,” Long said.

Unlike Coach E’s soccer club, the soccer family that Long has established at Bowdoin is predominately white —like each one of Bowdoin’s varsity teams. The racial composition of the team does not separate Long from his soccer family, but it does highlight a tension between members who identify with both athletic teams as well as with a minority identity on Bowdoin’s campus.

“In my time here, there hasn’t ever been a black member of my team who has also been an active member of Black Student Union,” said Long. “When you’re introduced to a team in your first semester of college, branching out of that social environment is difficult. I know for some of my black teammates, it feels like if you’re not a part of the family that is BSU beginning in the fall, how are you going to pretend to be a part of it in the spring? There’s a feeling of insecurity about whether or not your experience as a black, student-athlete at Bowdoin is ‘black enough,’” he said.

Long’s question of whether his Bowdoin athletic experience is perceived as “black enough” highlights a tension at Bowdoin that is common among athletes of color: strongly identifying with a particular racial group while also identifying with a group in which a majority of the members are of a different race. As he explains, identifying with an athletic team at Bowdoin as a black student made Long’s affiliation to a black student group feel precarious.

It is this same tension that brought Long to Athletes of Color—a group forged by the integration of two key aspects of his identity.

“The needs of athletes of color vary from the needs of other students of color at this school. At the same time, though, the purpose of Athletes of Color and these affinity groups are very similar—it’s all about creating a family at Bowdoin, one that serves your needs,” he said.

Long’s experience at Bowdoin is a product of his upbringing as a black man in conjunction with his experience as an athlete. It has, too, allowed him to find the family at Bowdoin with which he has formed deep bonds. More importantly, it has become the family that Long has leaned on facing the end of his soccer career as he once knew it. The question an athlete faces is not about the person that is left after they hang up their cleats, for the day or for the rest of their lives. They are an athlete forever. On the surface of their skin lives a memory of the grass stains that can never be washed out.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: