Hating Immigrants: America’s self-destructive tradition

September 20, 2019

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Kodie Garza

Kodie GarzaI was a sophomore at Bowdoin when Donald Trump was gaining momentum in the presidential election in spite of his xenophobic rhetoric. Anxiously dreading a near-fascist regime in the event of a Trump presidency, I talked with my mother about getting reacquainted with Nigeria, my mother’s native country. The talk did not go well and after debating the idea for an hour, my mother finally admitted, “We have no place to go! The Nigeria I knew in childhood doesn’t exist anymore. I would be a foreigner in my own country.” What I initially took for exasperation in her tone was actually broken-heartedness. She had fond childhood memories of Nigeria as a beautiful and safe black country, so it pained her to know that I did not feel at home in America—my country—and that she could not provide me with an alternative.

Much of my thinking these days roams to that moment, especially this summer when my family received the call that my aunt had been shot on the road in Nigeria. My Aunty Funke, a Nigerian native, had recently returned to Nigeria from the United States. She was headed to Lagos with an entourage when some drivers suddenly began to barricade the sides of the street with their vehicles. Other drivers, more familiar with what was going on, quickly drove away in time. My aunt and her entourage did not realize that the barricading was part of a routine marauding by armed bandits. The armed bandits approached my aunt’s van—while everyone in the car managed to escape except her—and fired into the car, striking her. She eventually succumbed to blood loss. My aunt had survived breast cancer twice, was managing her diabetes well and had an indomitable will to live for her children and grandchildren. Whether it was the police precluding her from getting immediate medical care due to demands for a bribe or the medical responders not stopping her bleeding in time, I could not help but feel that it was Nigeria that killed her.

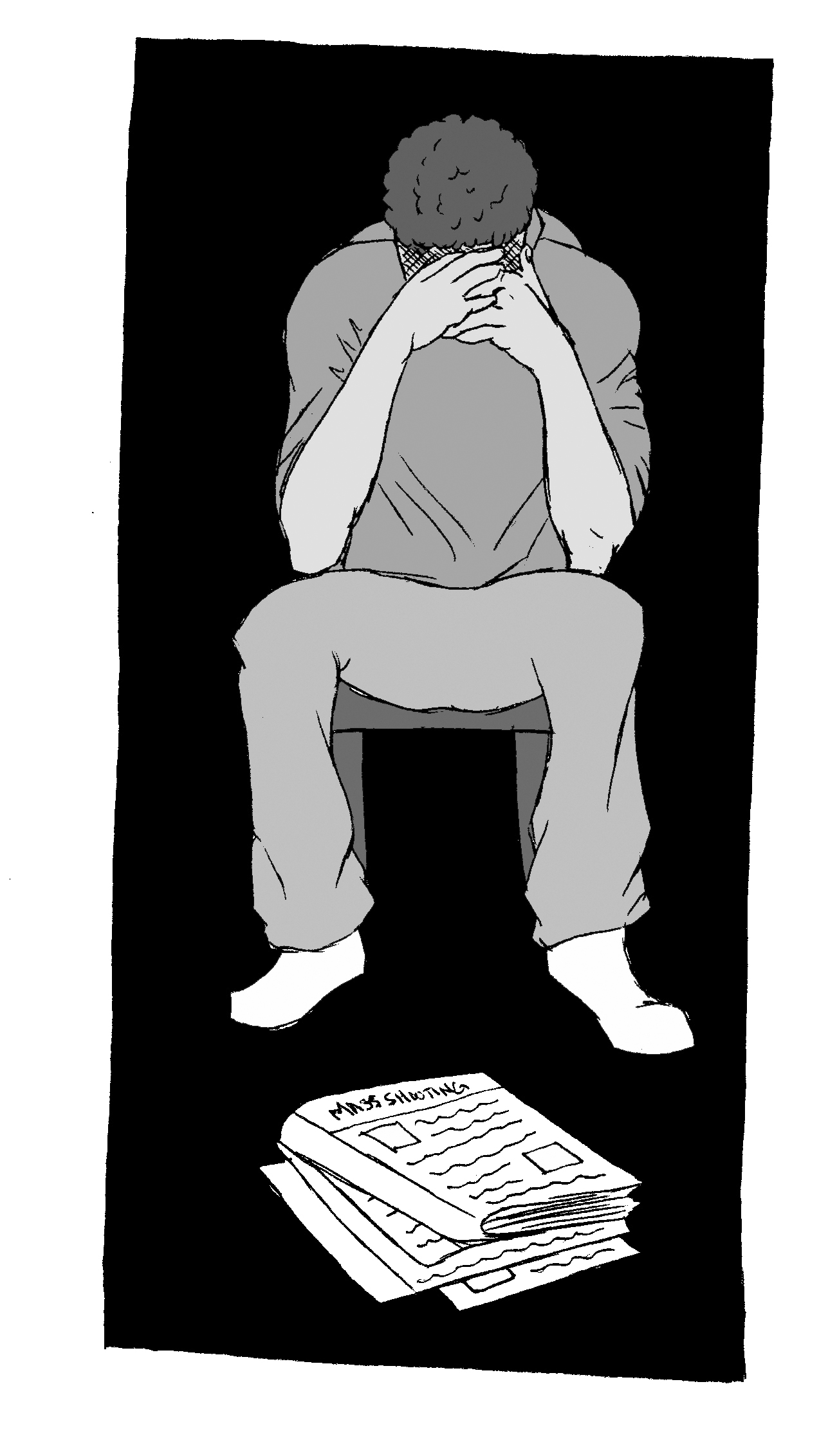

But summer continued and so did the mass shootings in the United States. Each breaking news segment about a mass shooting was a trauma trigger for me. My “Trump Anxiety Disorder” worsened as I feared that cousins in Texas or Ohio were also casualties in the shooting, before being reassured of their safety. Our commander in chief has spent most of his presidency spreading lies about Mexicans and other non-white immigrants ruining the country and in turn, empowering hatemongers like the El Paso shooter to act on those sentiments.

Turning away immigrants is not in America’s best interest. Immigrants and children of immigrants have become high school valedictorians, Bowdoin graduates and among the highest-performing workers in the country. I owe my existence to immigration and so does America. A xenophobic America is not rational; it’s an oxymoron.

From the Japanese-American internment camps to the congested detention centers for Latinx migrant children, the venom towards non-white immigrants seems to go deeper than the venom for Irish or Italian immigrants not so long ago. In July, the President told four congresswomen of color to “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime-infested places from which they came,” even though they are all Americans and all but one are natural-born citizens. His comments reveal two tropes of xenophobia: blaming the victims and thinking of them as subhuman. The immigrants that arrive here are generally not responsible for the turmoil they are escaping from. Aside from corruption, Nigeria struggles with national insecurity—from armed

robbery to kidnapping for ransom—none of which was my late aunt’s fault. Immigration can be a catch-22 that causes you to feel like a perpetual alien, forever a foreigner in both the land you emigrated from and the one you sought refuge in.

With her name all over Nigerian news outlets, I wished my Aunty Funke could have become a martyr whose death would transform Nigeria, but I won’t hold my breath. In the meantime, I desperately need America to feel like home for her children and grandchildren, and for mine.

Osa Fasehun is a member of the Class of 2018.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: