Virtual reality: to the classroom and beyond

May 3, 2019

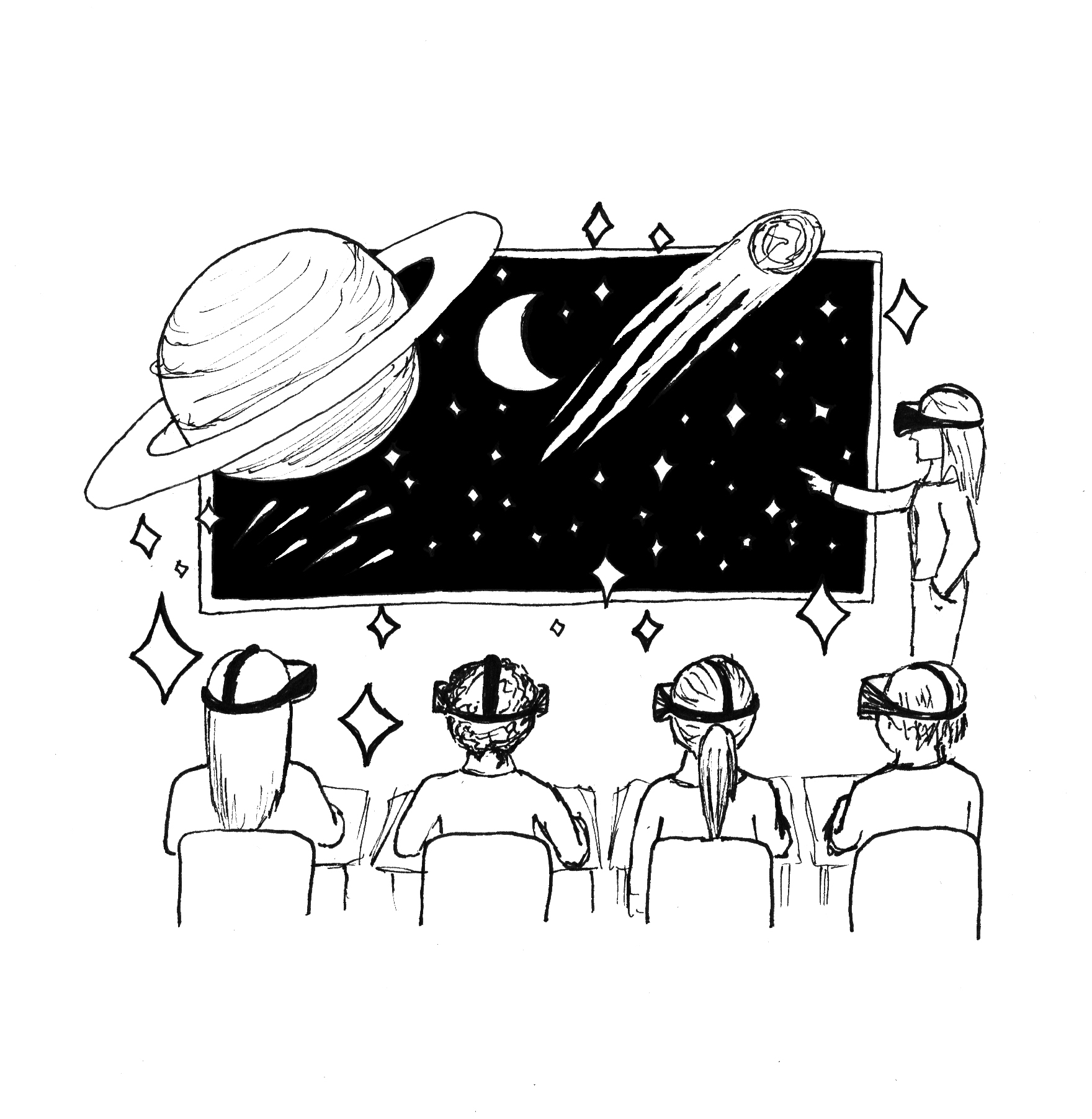

This Monday, I traveled to space. While my corporeal body remained in the familiar comfort of the first floor of Hawthorne-Longfellow Library, my perception was responding to a different world altogether—the unwieldiness of zero-gravity movement and a limitless expanse of black, punctuated by hazy starlight. I became dizzy, convinced that I was in space and the Earth was revolving below me—a small, blue and green mass 250 miles away. The virtual reality headset was working its magic.

There were subtle hints tethering me to reality, not unlike the tether that connected my imaginary spacesuit to the International Space Station. The headset, for one, sat unevenly upon my bun-topped head, allowing pockets of sunlight to seep in through the periphery of my virtual reality glasses. I could see the linoleum floor, solid beneath my feet, which broke the ruse of zero-gravity weightlessness. My hands clung clumsily to two joysticks that mimicked space gloves but lacked the fluidity of motion I was accustomed to as an able-bodied person. And yet, despite these hints, my stomach still dropped, my head still felt dizzy and my eyes were still in awe of he what was before them: space.

Exploration by virtual reality is just one of the myriad of ways Bowdoin is aiding student interaction with technology. This week, in an attempt to learn more about the technology around campus that students may not be aware of, I spoke with Senior Director of Academic Technology and Consulting, Stephen Houser.

“One of the things that we [in academic technology] do is help faculty and students use technology in their research and education,” said Houser.

The department manages Blackboard, assists the Center for Learning and Teaching and collaborates with the Department of Digital and Computational Studies. Staff help support faculty’s data-driven research as well as providing students with the latest education technology, including 3D printers and Computer-Assisted Design software.

Houser admits that there are dangers in oversaturating a classroom with technological aids.

“I love technology, but not everything is a computer solution. One of the challenges is finding where not to put technology as much as where to put technology,” he said. “A group of students in a roundtable discussion about a book is very fruitful and productive. It is a matter of experimenting, figuring out what works and what doesn’t work.”

I pointed to the irony of discussing technology in a library nowadays. Brick-and-mortar libraries are losing out to academic databases and online book piracy; the future of these institutions remains unclear.

“A lot of what librarians do is very similar to what we in academic technology do. They focus on traditional research methods, while we work with data analysis. These are simply different perspectives on the same research,” said Houser. “We’re taking technology and applying it to these traditional things that [librarians do] and getting new results. For example, I love reading books, but it’s also interesting to get that meta-view of a book afforded by an algorithm, which can do a text analysis and find patterns amongst the words. It lets you see a little deeper into the text and get a deeper understanding of the story.”

Houser used an example to illustrate his point.

“We had some students do research with Oliver Otis Howard’s letters from [the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives]. They were hoping to discern Howard’s social network from the addresses on his letters,” he said. “In this way, they could see who he was in communication with the most and where they were. We didn’t look at the content of the letters, but the address and metadata were observable. Being able to quantify the thing you’re observing helps.”

But how does academic technology make sure that every student is equipped with the skills necessary to do this type of research? Houser pointed to THRIVE as a program that helps students learn these skills. THRIVE is a college-wide initiative designed to foster achievement, belonging, mentorship and transition for students of low-income, first-generation or other underrepresented backgrounds on campus.

“For the THRIVE program, we look forward and try to think, ‘What are the skills that students need to achieve the same competency on the computer?’ On the basic level, [students should] be able to evaluate accurate sources of information, navigate the Bowdoin website and use the academic databases,” said Houser. “But the more nuanced questions are the more important ones. How do [students] learn to participate online? How do we teach them to interact with other people through these technologies?”

These questions are valid and deserve to be more thoroughly discussed in the coming years, as technology continues to become more ingrained in our daily lives. Hopefully, this column started some of that discussion. For now, however, I’ll continue to mess around with H-L’s virtual reality headsets.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: