June Vail: the unsung heroine of Bowdoin dance

April 19, 2019

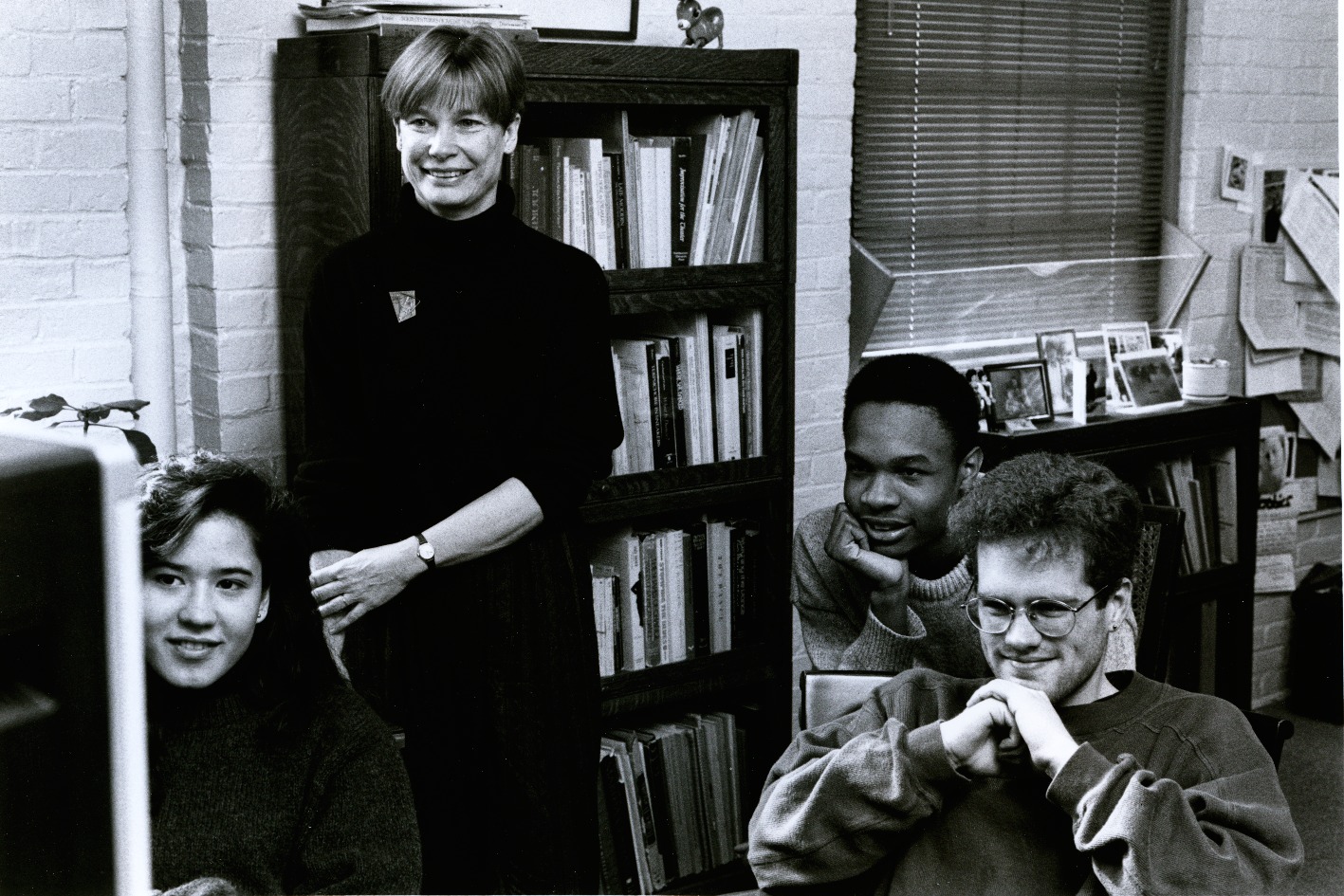

COURTESY OF GEORGE J. MITCHELL SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

COURTESY OF GEORGE J. MITCHELL SPECIAL COLLECTIONSWhat were the first dance classes offered at Bowdoin? The answer, according to Professor of Dance Emerita June Vail, included technique, repertoire, choreography and a senior seminar that took place in Coles Tower.

Though her name may not be familiar, Vail remains the unsung heroine behind the founding of Bowdoin’s dance program. For over a decade, she was the only faculty in the dance department, eventually going on to chair the department when it was officially established in 1986. She remained chair of the department in the early 2000s before retiring in 2011.

After teaching at the College as an extracurricular instructor for several years, Vail began teaching more formal classes in 1971. She was first introduced to Bowdoin through her husband David Vail, Adams-Catlin professor of economics emeritus. With the support of the College’s deans, she single-handedly built a dance program from scratch, pushing for a studio space and increased resources.

“I became a professor, which I never expected to be in the beginning,” she said. “That was not my aim. [But] I always felt I could do it.”

The program had humble roots—none of the dance classes were initially for credit—but students who shared a love for dance naturally gravitated towards each other.

“It was a very self-selected group who were very dedicated, and who really danced for four years or more,” she said. “Even some of them stayed on after they graduated.”

At the time, Vail was just a few years older than most of her students, which imbued a playful, friendly dynamic into her classroom and contributed to the department’s sense of community that persists today.

“We really had a good time. It was serious, but we had fun,” said Vail. “That was a really nice situation for me. And I wasn’t that much older than many of the students. I’m still in touch with many of [them].”

Unlike many of her faculty peers, Vail was very much in control of the program, teaching with a great amount of autonomy and personal style. After the program had established itself, Vail persistently pushed for classes to be offered for credit, even when others were less enthusiastic about the department’s prospects.

“In the ’80s, there was a push toward the theatre program, which was also not a credit program … So at that point, we explored the idea of a department,” she said.

The endeavor of building an entire department from scratch was not without obstacles. Vail and students had to learn to cope with various challenges and assumptions that did not always manifest themselves in overt ways. For example, the injured dance students, who needed physical therapy, were not allowed to receive treatment from the athletic trainers.

“There was friction,” Vail said. “But I felt like we overcame [the obstacles]. And, I think for a lot of the time that there was a general support of performing arts really—[even] if not in the way of financial [support].”

One of Vail’s key initiatives was to advocate for studio space for the dance students, who initially practiced in Sargent Gymnasium and did not get their own studio space until a decade later.

“We had to fight our way in because there was a lot of competition for the space, and they weren’t so sure they wanted to have women—well, even men dancing in the gymnasium. But we [won] them over,” she said.

Vail’s vision for the program is rooted in her knowledge of dance anthropology and cultural history. In a manner truly ahead of her time, she designed a dance curriculum that spanned disciplines and practices. In 1973, she taught a course on dance history and artistry from World War II to the present, along with collaborative courses featuring faculty from the fine art and music departments. Under her direction, students also put on annual performances in Daggett Lounge, Pickard Theater and on the museum steps.

“I was really interested in teaching not just studio courses, but also just like an art,” she said. “And that was always the focus for me, to make it a comprehensive program that involved studio work, technique, choreography … [as well as] history [and] criticism.”

Today, the dance program continues to thrive under Vail’s legacy, cultivating the creative community that she had envisioned when she first got to Bowdoin.

“I have to say that for me, [it was] the privilege of coming in and starting something from scratch and having a vision of what it could be on this campus with the students who are here … And what it did was bring together students who would not otherwise probably have overlapped in terms of their social circle,” she said.

Vail’s story, with her vision and relentless pursuit, is emblematic of the spirit of liberal arts. In an age where financial motivations preoccupy the minds of many, her story harkens back to the joy of learning and the solace offered by the arts.

“There’s just a real emphasis on the hard sciences and vocational work,” Vail said. “But I feel as if the purpose of a liberal arts education is really to introduce people to things that aren’t narrowly defined … And people can enjoy the arts for the rest of their lives.”

Nell Fitzgerald contributed to this report.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: