What I learned from my mammograms

April 5, 2019

During my first mammogram, I put my shoes in a locker before entering an inner waiting room. After I passed the front desk and made my way down a hallway, I was handed a robe the color of chewed bubblegum. For some reason I was reminded of when I went to a spa and shuffled around textured rock tiles, barefoot and sweaty. But this was not a spa, it was a professional, medical building, and everyone in the waiting room was wearing shoes. I retreated to my locker. Shoes stayed on.

During my second visit, I put the robe on backwards by accident. The shoulders were huge, and, when the belt was tied tight, I looked like a wasp with scrubs on, which I found simultaneously amusing and chic. Again, when I entered the waiting room, I knew something was off. Right after I realized what separated me from the others, an attendant said “your robe is on wrong, sweetie.” I put on my best “Ah! I see now!” face and went back.

During my third visit, I had a sneaky idea that I would put on multiple robes, just to see if I could. “But, you’re not here for that,” I reminded myself and continued to the waiting room— shoes on, robe tied correctly.

Two years ago, I found a knot curled up, tight beneath my skin. It was not small, and this was the rationale I used to believe that it was not harmful. If I really had a tumor this large inside of me, I would be in trouble. I didn’t feel in trouble, therefore it could not be a problem.

But when my doctor felt it and said “There’s a lump,” I felt a cold rush of terror.

There was silence, then I said, “Am I going to die?”

“No,” she replied. “But it should be checked out and monitored.”

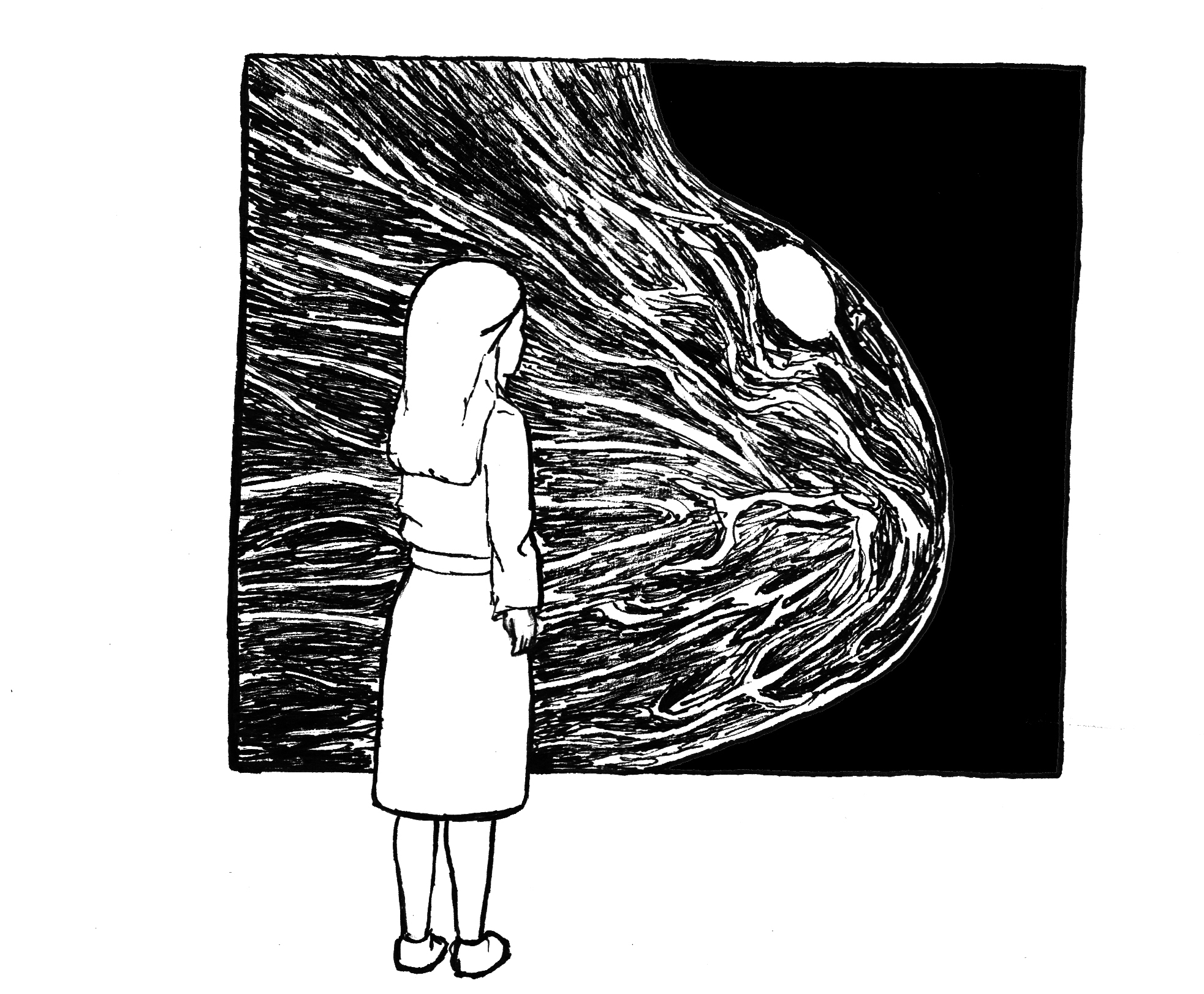

All I felt was panic when I scheduled an appointment. Panic with my mom in the car. Panic in the waiting room while drinking a cup of hot chocolate. Panic with the robes. Panic as the technician spread goo across my chest while humming an upbeat tune. Panic when I saw a foreign body on the monitor, pulsating with the beating of my heart.

Each visit I received good news, but also left with a sense of powerlessness, feeling at the mercy of an amorphous shape on the screen.

This feeling was not unfamiliar. Freshman year, I had come to the realization that the landscape of my physical health had changed. No longer was I fit and healthy; I was anemic, exhausted and covered in rashes. I now had infections and appointments. To my great displeasure, I felt that I had become one of the sick kids. For some reason, in my high school these kids seemed to be members of the landed gentry. I was always envious of how they got to skip tests and gym class to stay in their suburban compounds, in their tricked out basements; but despite this, they always seemed unhappy.

Now I understood. We often hear the phrase “listen to your body,” but my body and I were speaking different languages.

My initial reaction was to think, often and bitterly, “I am too young.” But then I decided to try.

I thought I had figured everything out: I paid attention to what I ate; I took my supplements; I reorganized my sleep. But December of sophomore year, I dragged myself to winter break with a sinus infection and a mysterious pox-like rash. It was so bad that one of my friends simply said, “woah,” when I turned around to greet him in Thorne, like I had revealed that I was the Bride of Chucky. “Woah.”

Back home, a dermatologist chalked this odd reaction up to allergies, weather and stress. I was frustrated, not just because now I had four different creams, but also because these were all factors that were, mostly, out of my control.

Men and women brandishing acai bowls on Instagram sell not only an image of psychical perfection, but one of total control over their bodies. This may become dangerous when people try to mimic their S-curved torsos, or their magical vegetable-based cures for cancer. But it is a lie. Many health issues are beyond our control and won’t fully resolve, despite our best attempts. What consists of health is a complicated nexus; and, for everyone, the exact calculus that makes up “physically healthy” is often in flux, and our control over our health differs.

We mainly talk about knowing yourself as an emotional journey. This is true. However, it is also a physical one. And a large part must be learning what I can help, and what I can’t lose sleep over. I feel nauseous when I touch the lump on my chest. It’s not my friend; I wish it would leave. But it reminds me, too, that perfect control over my physical health is an illusion.

Aleksia Silverman is a member of the Class of 2019.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: