The other side of the wall

March 1, 2019

Dalia Tabachnik

Dalia Tabachnik“Y el muro … ¿funcionará?” “And the wall… will it work?” asks an older man, who is kind and usually smiling but now looks concerned. He has dark skin, wrinkles around his eyes and a t-shirt torn at the sleeves. I converse with him and his wife while sitting in their backyard, where chickens roam and neighbors lean over the fence to say hello. Their son worked for 11 years in wood processing and other jobs in the U.S. and is now likely trying to return to Mexico—though his parents haven’t heard from him in a month.

“What will it be made of? Will people be able to climb it?” They inquire with faces that imply I know the answers. They say it’s harder now, that their son walked through the desert and lost most of his group crossing 15 years ago, but that nowadays he probably wouldn’t find a way to cross. They say their son was treated well, but some of his coworkers weren’t paid and didn’t feel they could appeal. The parents explain that, as far as they understand, their son went to the U.S. because of a curiosity about life in another country and a desire for better pay.

“¡Nos odian!” “They hate us!” exclaims a young man, chatting and joking with us, beer in hand. I stand on the balcony of a cheap beachside hotel, talking to a 28-year-old lawyer who believes Trump (and many American politicians) hates Mexicans. He says he wanted to visit the U.S. once for vacation, but the consulate contended that he and his dad would try to stay for work in the country. He says they both provided proof of their steady employment, and despite the Americans’ skepticism, they (just barely) got travel visas for the family.

“Una hora y media, dos …” “An hour and a half, two…” estimates a young woman casually while walking in the middle of a lakeside road. She studies in Mérida but comes from Northern Mexico. She goes shopping in San Diego and visits family in Pasadena about every month. She’s estimating how long it takes her to drive there from her house, but when I ask about the border, she admits that during rush hour, it could be up to an additional three hours just waiting in the line. She says she likes it in California; the shopping is good.

“Mejor, voy a Canadá.” “I’ll just go to Canada,” concedes an older woman with a defeated half-smile. I sit in my dining room eating enchiladas de mole, talking to my host-mom. She says that, since the U.S. is one of the only countries that requires an application for a visa for even a vacation, it’s not worth it. She hates long flights, but she’ll fly to Canada instead of dealing with American bureaucracy.

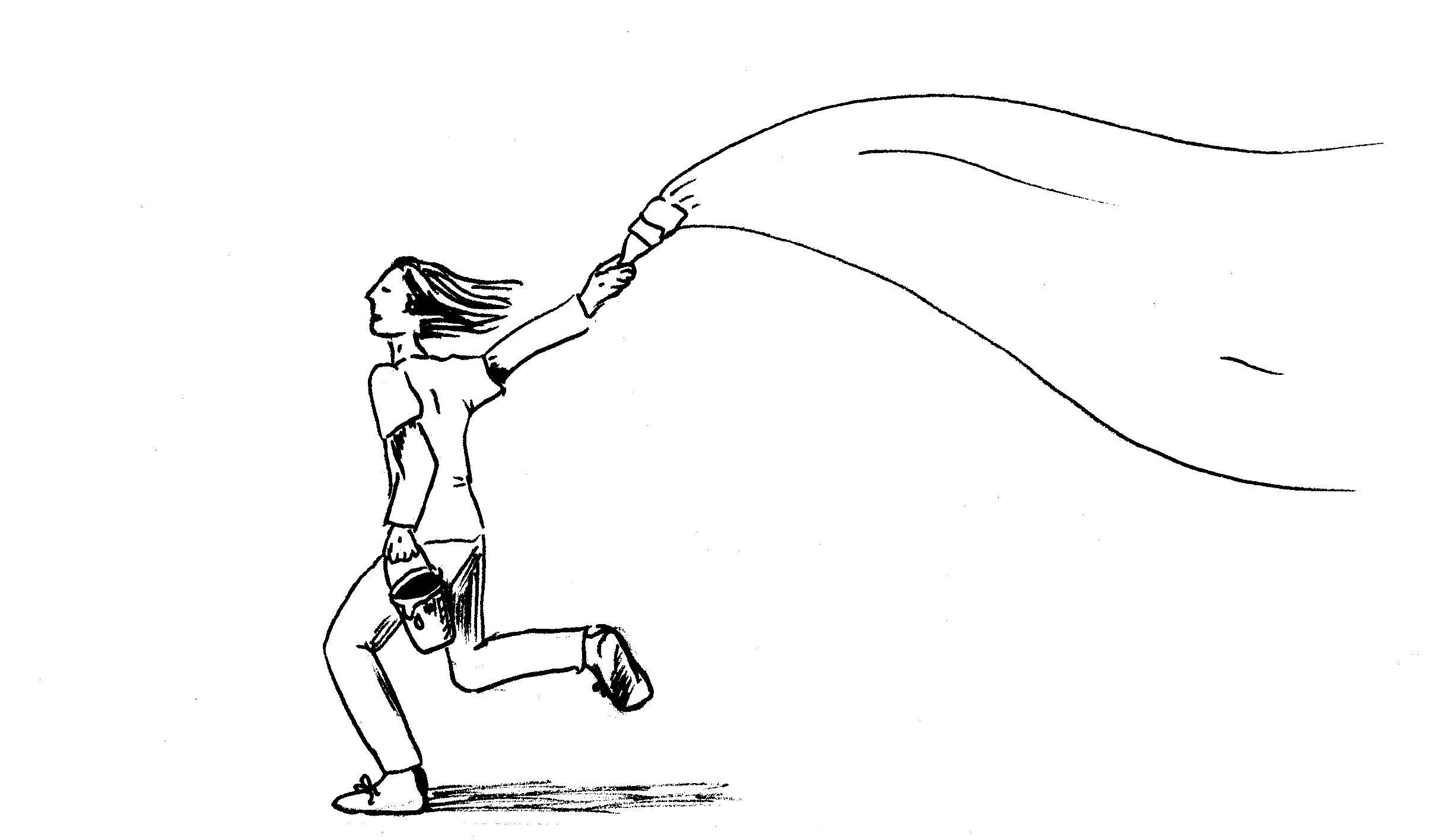

“Tal vez si construyen el muro, lo puedo pintar allí.” “Maybe if they build the wall, I can paint it there,” dreams a young woman while snacking on pizza. She is a friend from university and has a job painting murals—incredibly beautiful ones. She says she wants to paint one telling the U.S.’s history with Native Americans and immigrants. She questions what the response would be, imagining pushback because she is a foreigner and wants to display critical opinions of race relations in the U.S. We discuss how, though it’s complicated and vulnerable to plenty of criticism, Mexico’s history of colonization and mestizaje is mostly out in the open. In contrast, American students struggle to articulate anything they learned about Native Americans or immigrants in history class.

In only a month and a half, I have found myself in each of these five conversations. I did not seek out these stories; they are not interviews. They are the everyday reality of people who are now part of my everyday reality. They may not be scandalous or intimidating or even shocking, and that’s the point: neither is Mexican immigration. As an American in Mexico, I have an obligation to amplify these voices, combatting the “single story” (Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s term) the U.S. has of Mexico. It is not all tequila, sombreros and partying, nor is it defined by cartels, drugs and guns. There are 129.2 million stories here, and I have told you bits and pieces of only five.

American media is worried about a potential wall, a recent “state of emergency,” but those things already exist. We have built—with anger, fear, xenophobia, force and domination—a wall between our untouchable American Dreamland and this perceived wasteland. We have created a state of emergency wherein some people cannot get paid a living wage, are abused for their economic value, are denied their human rights or are feared before speaking a word.

Like my host-mom says, “Que construyen el muro, para que vean: no es la solución.” “Let them build the wall, so they see: it’s not the solution.” We will just come and paint it over with images of our despicable history of imperialism and colonialism anyways.

Anna Martens is a member of the Class of 2020.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: