Bowdoin in history: half a century of Africana Studies

March 1, 2019

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin CollegeFifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination was a fresh wound in American public memory, and white institutions across the country were beginning to confront major gaps in their course offerings and their woefully homogenous student bodies.

In February of 1969, the nation-wide Black Campus Movement came to a head. Demonstrations demanding increased diversity, in both student body and curriculum, at the University of Wisconsin at Madison drew 900 national guardsmen to the campus in alarm. Within the following months, dozens of colleges and universities quickly established programs in Black studies, both proactively and out of “white guilt”—Bowdoin included.

On May 12, 1969, the Black Curriculum Committee, composed of Bowdoin students and faculty, proposed a plan to create an Afro-American studies major the following semester. The faculty approved the plan on May 14. Over the course of one summer, the College went from offering just one course relating to Africana studies to offering a full major’s worth.

By 1969, the civil rights movement was slowing down. Even BUCRO, the Bowdoin Undergraduate Civil Rights Organization, was waning in numbers and activity. Opinion pieces by non-members in the Orient wondered whether BUCRO was “dead.”

What had the College looked like in the 1960s, while state-sanctioned violence against black Americans sparked protests in much of the country?

“A lot of the momentum in the civil rights movement was people of college age, but not at Bowdoin,” said Dan Levine, the Thomas Brackett Reed professor in history and political science emeritus, who arrived at the College in 1963. “Maine was sort of a backwater of civil rights activity, and Bowdoin was a backwater in a backwater.”

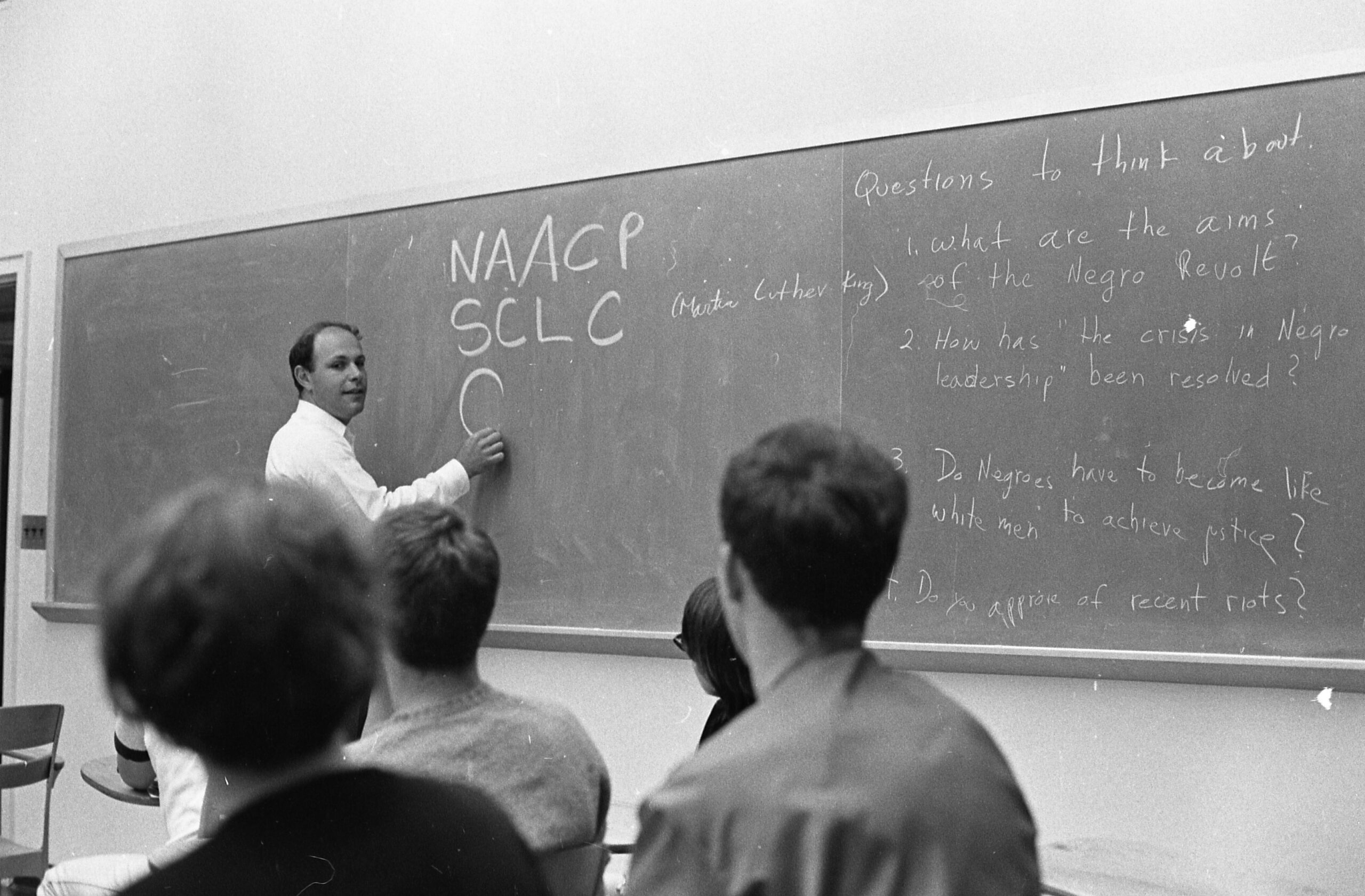

In 1963, Levine was a young professor teaching about the progressive era and the welfare state. Throughout his undergraduate and graduate education, he had never been offered a course relating to Africana studies. Such courses, he said, did not yet exist. But he followed the civil rights movement and attended the March on Washington that August where he heard King speak in person for the first time. He would hear King a second time in 1964, at the First Parish Church on Maine Street.

It was after that visit from Bayard Rustin and King, Levine recalled, that Bowdoin’s own civil rights activism emerged, albeit quietly. A small group of students founded BUCRO, which organized forums on race and education, and initiated Project 65, an admissions effort intended to increase enrollment of African Americans at the College. And Levine, the then-faculty advisor to BUCRO and the Political Forum (the group which brought King and Rustin to campus) taught Bowdoin’s first-ever course relating to Africana Studies.

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College“In about the fall of ’64 [when] Stokely Carmichael said in a speech: don’t come to Mississippi and teach us how to vote—we know how to vote. Teach black history at Berkeley. Those are the people who need it. So I thought to myself, OK I’m not at Berkeley but I’m at a white college. Those are the people who need to know about black history,” said Levine.

“I said, well, I’m not gonna go to Mississippi; I’m no good at teaching people how to vote anyway. But what I can do is teach black history,” he said. “So what I’ve done with a couple of subjects that I knew nothing about, I have a seminar in it. And the students and I learn it together. So I had a seminar on the civil rights movement as it was happening … I educated myself and the students educated me and I educated them.”

Levine continued to lead courses on the civil rights movement at Bowdoin for the next 46 years, devoting much of his research to the life of Bayard Rustin, who inspired him following his ’64 and ’78 visits to campus. He would later join the NAACP chapter in Portland, chair the College’s committee for non-western studies and sit on its committee for disadvantaged students and committee for Afro-American studies (CAAS)—three faculty and student-led efforts to diversify the curriculum and student body.

“Asia didn’t exist. Africa didn’t exist. Russia didn’t exist,” Levine said of Bowdoin’s history curriculum upon his arrival. “It was a very narrow view of the world. It was a very narrow view of American society.”

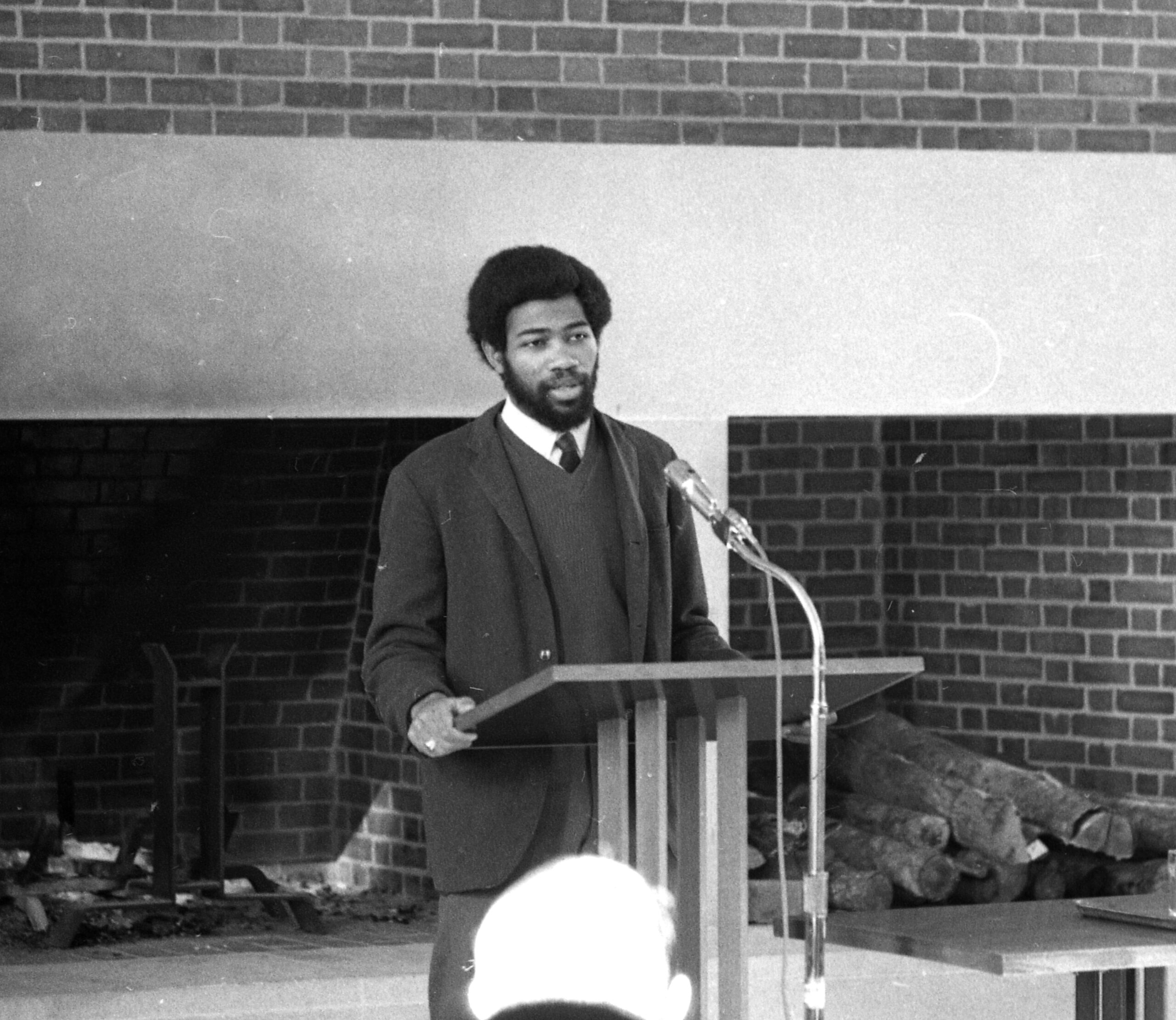

Beyond this curricular shift in 1969, Bowdoin also saw its first affinity group form: the African-American Society (Af-Am). With it came the John Brown Russwurm African-American Center, a place for the society to gather. Among its founding members were Virgil Logan ’69 and Robert Johnson ’71, two members of BUCRO who were vital figures in developing the Afro-American major, organizing the first Martin Luther King, Jr. day celebration in Maine in 1970 and recruiting the program’s first chairman and the College’s first African-American professor, Reggie Lewis.

In its first year, the mere presence of Af-Am disquieted many white students on campus, who feared “separatism”—going so far as to call it “Black Nazism,” according to the Orient from 1968-69. In a November 8 letter to the editor, Levine spoke out against this growing unease.

“It must, by necessity, be an all-black organization,” wrote Levine. “It is not discriminating against white students; white students are simply irrelevant to its functions … I hear white students ask how they help [the civil rights movement.] One way may be to support Afro-Am, and keep hands off.”

For the most part, they did. However, there are a handful of reports of white fraternity brothers harassing members of Af-Am and vandalizing the Russwurm house. The College was apparently slow to respond.

“The administration treated the incident as though it were an embarrassing prank,” wrote members of Af-Am to then-president Roger Howell following his choice not to discipline the students. They asked that he suspend them—there is no correspondence confirming whether he did.

Despite this push-back, Af-Am continued to grow, as did the Afro-American Studies program. Lewis resigned within two years in protest of the College’s insufficient funding toward the program; with his resignation, he asked that the remaining of his salary be donated to Afro-American Studies.

The Russwurm House became the first African-American cultural center in the state of Maine. CAAS remained active into the 1970s and ’80s, and made it its mission to recruit more African-Americans, both faculty and students, to the College.

Meanwhile, Levine continued teaching African-American history until 2010. For a few years into retirement, he continued with research on campus, but has recently stopped, devoting time to practicing the cello and being with his grandchildren on Mere Point. When asked if he continued to participate in demonstrations after the ’60s, he said, “my activism is in my teaching.”

In the fall of 2019, Af-Am, Africana Studies and Russwurm will celebrate their fiftieth year anniversary with a weekend-long symposium celebrating alumni, the discipline, African-American art and the past fifty years of African-American students at Bowdoin.

“It’s wonderful,” Levine said. “It ought to happen every four years or so, that the students recall a little about what the world was a half a century ago.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: