Growing up in activism: a tale of Berkeley, California

September 28, 2018

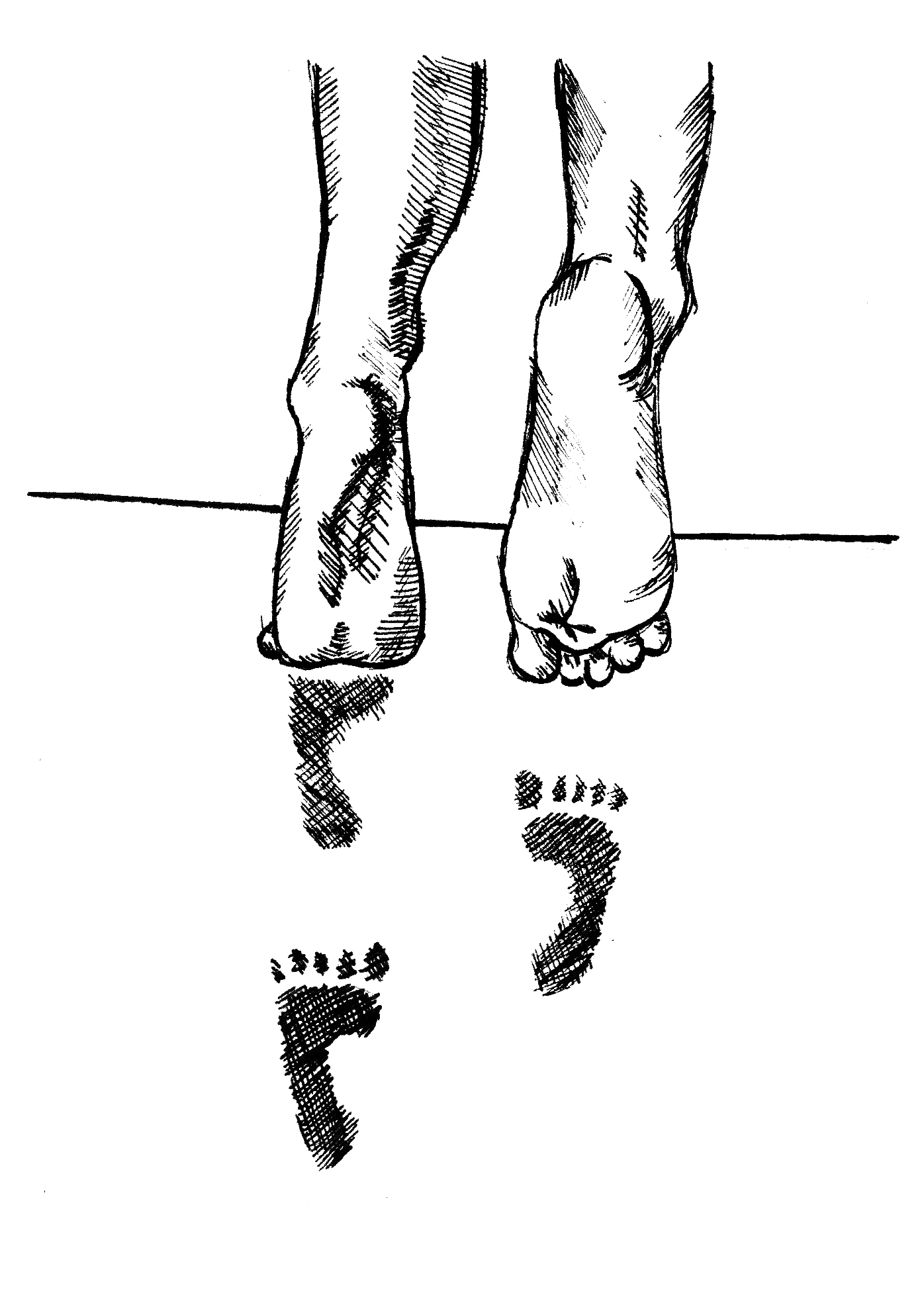

Lorenzo Meigs ’21 has lived in the same city for practically all of his life. I’ve always been fascinated by my peers’ relationships to place, especially by those who seem to embody their homes. Meigs is one of those people. From often going barefoot in the summer (to my dismay) to a proclivity for political action, to wearing linen shirts on canoe trips, he is effortlessly Californian. I’ll admit, my fascination with people like him is part admiration and part jealousy. What must it be like to really be able to claim one place?

In this column, I’m seeking to paint a portrait of both a person and the place or places that are meaningful to them. I’m starting with Meigs because, at first glance, it seems that living in Berkeley his whole life is all there is to know. But as I know all too well, it’s always a little bit more complicated than that. Meigs’s father moved around Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey growing up. His mother spent the first ten years of her life in Uganda, then lived in Texas, New Jersey and New York.

“They were really focused on me and my sister Rosa … grow[ing] up in one place … to really be able to put down roots and feel like we were genuinely from someplace,” Meigs said.

As he said this, I thought about how I often think about where I’ll live as an adult. I know that I don’t want to move around as much as I did as a child. That, despite how much I love being a student, I can’t wait to be done with my education so that I can settle down somewhere and not leave. The only problem is, I don’t know where. I asked Meigs how his parents decided on Berkeley.

“My dad … moved to Berkeley … in the end of 60s and beginning of the 70s, during the free speech movement. All the hippies really were there, [and] he was one of them,” said Meigs.

His father knew that if he was ever going to raise a family, he would return to Berkeley to do it. When he got a job offer in Berkeley decades later, he moved back with Meigs’s mother.

For the first 17 years of his life, Meigs lived in the same house, in a diverse neighborhood in Berkeley. When I asked Meigs to tell me something that happens in Berkeley that doesn’t happen anywhere else, he immediately noted the culture of activism.

“I think my first memory [of activism] was going to an Iraq War protest in 2004,” he said. “I remember being on my dad’s shoulders and seeing these men with huge guns, up on City Hall in San Francisco. And not really being aware of what we were mad about, but something was going wrong in the world.”

The culture of activism around him continued into high school. Every month, there would be a walkout, where Meigs and his classmates would gather on the quad and then march up the University of California, Berkeley campus. There, students would give their demands, addressing an issue within local, national or school politics. “I think some people just … wanted to get out of class,” he admitted.

This culture of activism led Meigs to reflect on Berkeley’s own internal issues as he grew older. “We are one of the most unequal areas of income distribution in the nation,” he said, “and a rapidly gentrifying area. Something that I really care about deeply now … is fixing what I see as the biggest issue in Berkeley which is … the [housing] crisis.”

As he approached graduation, Meigs knew he wanted to take a gap year after high school. He spent almost six months traveling outside of the country. I asked him if it had anything to do with living in one place his whole life, if he had grown sick of the monotony. He thought for a moment.

“That was definitely part of it …[but] I wasn’t homesick. Not really even once.”

This was surprising to me. I don’t know what I expected to hear—maybe that he longed for home every day, that it was terrifying to be away from the only place you’d ever called home. But of course it made sense. If you’re from one place, you’re bound to grow weary of it.

I wonder, then, why I am always longing for places. Sometimes I can’t name the place, but I can see it or feel it. It’s often a mood, or a color or just a memory. Maybe it’s because the root of my place anxiety is not that I moved so much, but that I never had a choice. Where you grow up—even if you’re grateful for it—is not a choice you get to make for yourself. I am always grappling with this, and so I asked Meigs if there is one place that feels like just his.

“The number-one place I always go to … when I go home is a park called Claremont Canyon Regional Preserve,” he said. “I call it the top of Dwight Way, because you go up this kind of busy street and as the traffic dwindles … it gets to this dead end with this hill.” He pauses. “There’s these eucalyptus trees …. There’s a little pass that goes through valleys at the end. And there’s a beautiful view … of San Francisco, and Oakland …. There’s a really nice big rope swing that goes out over this big hill.”

I can see it clearly. A place that feels like the top of the whole world.

“I felt like I was removing myself … I would be able to look down on Berkeley and see Berkeley lit up before me. And it felt like rising above everything,” he said.

Since I met him, I’ve wondered why Meigs decided on Bowdoin. “Bowdoin means intellectual inquiry,” he says after a moment. “It means … having amazingly interesting conversations with people. Not really about their lives but what their ideas are about how to live life.”

My own complicated relationship with place has made me extremely sensitive to the same in others. I am endlessly fascinated by people—by the people that raised them, by the earliest memories that shaped them, like Meigs’ memory of being on his father’s shoulders during the Iraq War protest in 2004, and I love seeing how learning more about these things adds the richest of dimensions to people. I marvel at the ordinary of who we are, and how extraordinary it really is.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: