Silencing the lambs: the danger of collapsing religion along partisan lines

September 21, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

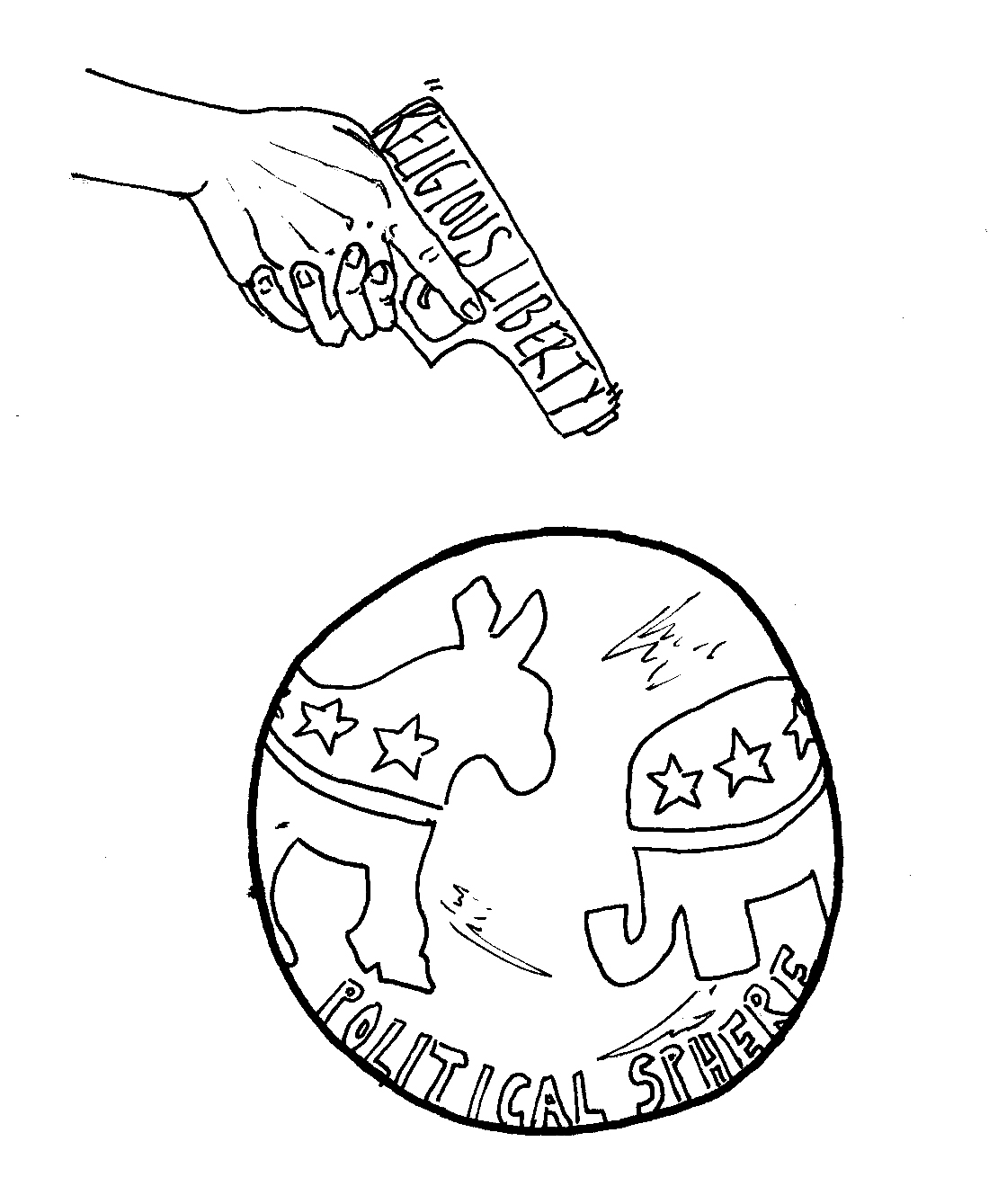

Since his nomination to the Supreme Court was announced in early July, Brett Kavanaugh has deepened already bitter partisan divisions. Now with the nomination itself hanging in the balance, it can be hard to assess the full range of Kavanaugh’s significance for the future of the American government. Behind the media frenzy over recent accusations and implications for the future of Roe v. Wade lurks an agenda that seems more latent, but which deserves equal attention: Kavanaugh’s push for “religious liberty.”

This has not gone unnoticed by large media outlets: the Washington Post decried Kavanaugh’s religious platform as “a political wet kiss for Trump” meant to distract the religious right from the scandals surrounding the White House. An examination of Kavanaugh’s decisions as a circuit judge of the court of appeals and the amicus briefs filed during his time in private practice paints a grim picture for the future of our highest court: an unmediated connection to an even higher, divine power. However, the discourse surrounding “religious liberty,” or rather, constraining it, is concerning to me.

Though I share the horror that the Post’s Sarah Posner has expressed at the proceedings thus far, it seems to me that much of the media coverage of the Kavanaugh hearings has come dangerously close to conflating Kavanaugh’s sectarian conception of “religious liberty” with Christianity as a whole. I am not breaking new ground in arguing for the separation of the “religious right” from the larger community of practicing Christians in America for our understanding of religion. Nor am I attempting to delegitimize the strength of the evangelical influence by advocating that distinction be maintained. Rather, it is precisely because of the weight of this sectarian influence that we need to re-evaluate the way we contend with the overlapping arenas of religion and politics. To truly understand what we risk losing under a sectarian implementation of “religious liberty,” it is imperative that we assess religious influence across the entirety of the political spectrum, not merely at its most vocal, volatile pole.

Reframing the weaponization of religious rhetoric as a bipartisan issue means contending with reductive language on both sides of the political divide. It is a crucial component of reconciling the striking difference between a “religious liberty” grounded in practice and the discourse-driven, sectarian understanding of “liberty” that constitutes Kavanaugh’s platform. With Kavanaugh poised to cement this understanding of “religious liberty” as an American universal, many Americans are at risk of having their rights compromised. To address this crisis, it is necessary to construct a self-aware, nuanced critique that carefully examines the religious dimension of this political threat. We cannot risk the careless, reductive language equating American Christians with the 81 percent of white evangelicals who voted for Donald Trump. Doing so alienates valuable allies in the fight against the increasing infringement of a sectarian, partisan conception of religion on larger society.

In fact, as the invocation of religious liberty has increased in the political sphere, some American Christians have shied away from open demonstrations of faith. For his new book, “Learning to Speak God from Scratch,” author Jonathan Merritt surveyed 1,000 American adults in 2017. He found that 87 percent of practicing (here meaning “churchgoing”) Christians avoided talking about their faith, with many confessing to “feeling ‘put off by how religion has been politicized.’” As Merritt states bluntly in his article for The Daily Beast, “The mingling of religion and partisan politics discomfits many Americans.” These are not, he is sure to specify, “the conservative faithful” who overlook Trump’s botched biblical references and support his fresh assault in the “culture wars” gripping American society. These are instead those who balk at Trump’s apparent inability to reference a single Bible quotation offhand or even pronounce the name of an epistle.

As Merritt notes, and as many Christians recognize, Trump traffics in rhetoric. As such, his “public religiosity” takes only what can be weaponized for his larger political agenda, leaving the particulars of religion behind. With major media outlets equating “standing for religious liberty [with…] standing for Trump and now for Kavanaugh,” this “public” brand of religiosity is subsuming the nuances of Christianity. There is no one Christian position, nor is there one representative religion per party. To reduce a spectrum of Christian practice to the “religious right” serves to further entrench religion in the political sphere, magnifying the opposition from a select group to the ideology of religion at large.

In the weeks after Kavanaugh’s nomination was announced, a group of 35 evangelicals, called the Red-Letter Christians, banded together to straddle the religiopolitical line and call for a “pause on culture war.” In these published testimonies, Roe v. Wade—which is cited by many as the reason for the sharp spike in evangelical voters during the 2016 presidential election—is placed within the larger context of national poverty and an expansive definition of life. It is efforts like these that expand Merritt’s argument, demonstrating that political and religious identities do not always fall along sectarian lines. As Reverend Alexia Salvatierra writes: “too often, evangelicals have been identified with only two political concerns instead of representing the full heart of God.”

I run the risk of sounding naïve. The “full heart” in particular seems too good to be true, too hard to wrench from the tangle of partisan and patriarchal influence. I am not advocating for a de-legitimation of Kavanaugh’s understanding of “religious liberty.” On the contrary, I believe that by identifying its sectarian, partisan nature, we can better understand the threat it poses to our national liberties. A crucial component of this understanding is the employment of a language of awareness, one that contends with fluid religious and political spheres. Naïveté lies in the hope that these spheres can become distinct. In their inevitable overlap, their symbiosis, it is crucial to tread carefully. The ramifications of quieting voices of protest because of their religious identification, like the Red-Letter Christians and those interviewed by Merritt, is too great to continue this kind of general, polarized discourse.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: