Untested complicity, A+ potential: Curricular reform can relieve students of color from the burden of teaching race

The second installment from the Diversity in Higher Education seminar

April 6, 2018

Diana Furukawa

Diana FurukawaThis article is the second installment in the Diversity Matters series where students in the Diversity in Higher Education seminar present research based on interviews with 48 seniors. To read the first installment, click here.

Students can easily go through Bowdoin with color-blind understandings of race unchallenged and undisrupted. People who have this color-blind view tend to believe that the best way to solve racial inequity is by ignoring racial differences. Ironically, not “seeing” race exacerbates racial inequity by overlooking the structures and institutions that have been built to benefit white people at the expense of people of color. Similarly, the College does little to rise above multiculturalism that encourages learning from others with different racial backgrounds without acknowledging the power imbalance between “multicultural” students and the white students who learn from them.

As course selection approaches, we turn to investigate how classes have helped students understand difference, how most coursework falls short of addressing inequity and what curricular changes Bowdoin needs.

Our research finds that:

1. Bowdoin has next-to-no required instruction or programming about race and its existing programing is limited in effect.

2. Courses (which are the most positively-viewed sites for conversations about race) largely and often fail to address inequity—racial or otherwise. The Exploring Social Differences (ESD) distribution requirement does not currently appear to fulfill its purpose, but has potential to establish students’ baseline comprehension of inequity.

3. The lack of race-related programming and the failings of most academic spaces to generate meaningful discussions about race burdens students of color to teach their white peers.

Apart from the recently-developed “More than Meets the Eye” first-year Orientation programming, Bowdoin requires no race-related education for its students. Furthermore, our data suggest that the impacts of programs like Intergroup Dialogue and community discussions—designed to critically delve into broadly defined issues of race—are limited and participation is self-selecting. As one student of color reflected: “If there is … a talk about diversity, it’s always attended by the same exact people and never by the people that actually need to hear it the most—white people.” Additionally, of the students who discussed partaking in these conversations at Bowdoin, 83 percent mentioned instances when negative experiences with or perceptions of these campus programs led them to feel discouraged from entering future structured conversations. Students confused by racial issues felt these programs were not good platforms to ask honest questions and gain a better understanding of race, and ultimately increased racial divides because of their self-selecting nature.

Diversity Matters

Students in Assistant Professor of Sociology Ingrid Nelson's senior seminar interviewed 48 seniors investigating student's experiences and understandings of diversity at Bowdoin. In this series, they present their findings.

The College fails at educating all students about race despite an overwhelming need for this education. This is a need that has been acknowledged at the institutional level with the creation of the Senior Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion and a need that is not particular to white students. As one student of color unfamiliar with the concept of cultural appropriation said, they sensed their peers’ expectation to be experts on race: “My friend who is white […] kind of made me feel dumb that I didn’t understand what was going on.” Another expressed feeling “outed as being a person of color,” and therefore presumed to be able to talk about race intelligently. The expectation of students of color to be actively-participating experts on campus racial issues allows white students to either ignore the fact of race or defer to their peers of color instead of being pushed to address the issues themselves.

•••

Studying diversity and racial inequity is a qualitatively and numerically limited part of the Bowdoin academic experience; furthermore when taken, classes that address these issues often do so insufficiently. For one, not all professors address current events and concerns in their classrooms. One student described struggling as some professors “just kept going on with their day” in the midst of racially-charged controversies on campus. Also, few majors require classes that investigate inequity: within the top eight majors for students in the classes of 2017 and 2018, there are only five ESD classes listed for this academic year. This distribution suggests that the majority of Bowdoin students opt into coursework that rarely confronts social difference. Compiled by Drew MacDonald. Source: "Understanding Diversity."

Compiled by Drew MacDonald. Source: "Understanding Diversity."

However, classrooms have the power to draw all students into critical thinking about inequity by providing spaces for students to partake in professor-facilitated discussions. Of the students who mentioned positive experiences with race-related conversation, 36 percent had experiences that occurred in a classroom setting. Classes, particularly those in the humanities and social sciences, were the only form of involvement in campus racial issues that students interviewed unanimously said improved their understanding of race. Our research found that class discussions can encourage students to critically examine their own racial identity and provide a positive space for students to process campus controversies. One student said their involvement in the Africana Studies Program “has been really integral to my interactions with diversity on this campus,” describing how learning hard facts and deepening their understanding of racism’s “historical context” have made it easier for them to discuss diversity. Another student expressed gratitude for an anthropology professor who, after a campus controversy during their sophomore year, led a class discussion without “assum[ing] that everyone knows about cultural appropriation.” The professor helped clarify the situation for students who were confused about cultural appropriation and “didn’t know where the line was.” These few mentions of class as a meaningful space for discussions on race and difference demonstrate the utility of classrooms for racial education, but also suggest that its reach must be expanded.

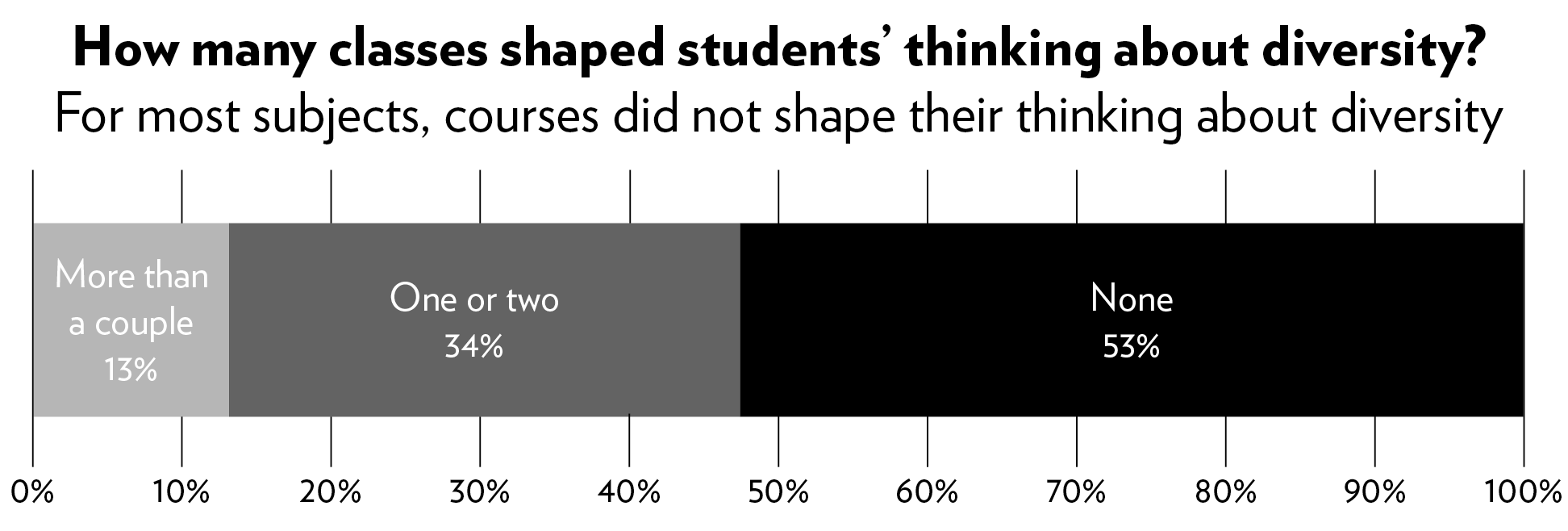

Every student is required to take an ESD that purportedly fulfills the goal of “develop[ing] awareness and critical understanding of differences.” However, more than half of interviewees asked about diversity and academic experience said that none of their classes had shaped their thinking about diversity. While some of this may be explained by the durability of color-blind understandings of race among students, it also points to the fact that many classes—including some meeting the ESD requirement—are completely bereft of meaningful discourse on inequity at all.

This educational void creates serious consequences, specifically, charging students with marginalized identities with the unpaid labor of sharing personal experiences and explaining basic concepts to their peers. One student of color felt this sort of sharing in the classroom was actually “a way for white people to hear … more sides … for their benefit.” While white students sometimes described being in class with students of color as personally enriching, “really helpful” and “valuable” as sources of information to “enhance … academic thinking,” many students of color struggled with the weighty obligation of representation. Some students of color expressed feeling like they need to speak on behalf of a whole group of people of their demographic. One expressed feeling tokenized: “There’s always a moment in which you notice that, like, ‘Oh my God, I’m the only black person in this class’ … and you just feel like you have to represent the black people.”

The students who take on this burden, in addition to all of their other academic and extracurricular responsibilities on campus, are not only taxed by the emotional labor of educating their peers, but also discouraged by the limited successes of their earnest efforts. This stress is only compounded by the discomfort and pressure women and students of color especially already report feeling in the classroom. One man of color, for example, said, “people here think that I’m breaking the stereotype of being a Latino male for being here on campus” because “people think that Latino males are not as successful academically.” As a result, he said, “it just puts me on an unlivable standard.”

Without an institutionally supported emphasis on engaging with racial politics and other issues of difference and inequity, Bowdoin places the responsibility of educating students about these important topics on the shoulders of marginalized students. Unlike professors and trained staff, students of color are uncompensated for teaching other students. No school should expect its students to educate their peers in such a grossly imbalanced manner, which permits students graduate with uninterrupted color-blind ideas of race, underprepared for the changing world and geared to reproduce social inequities.

•••

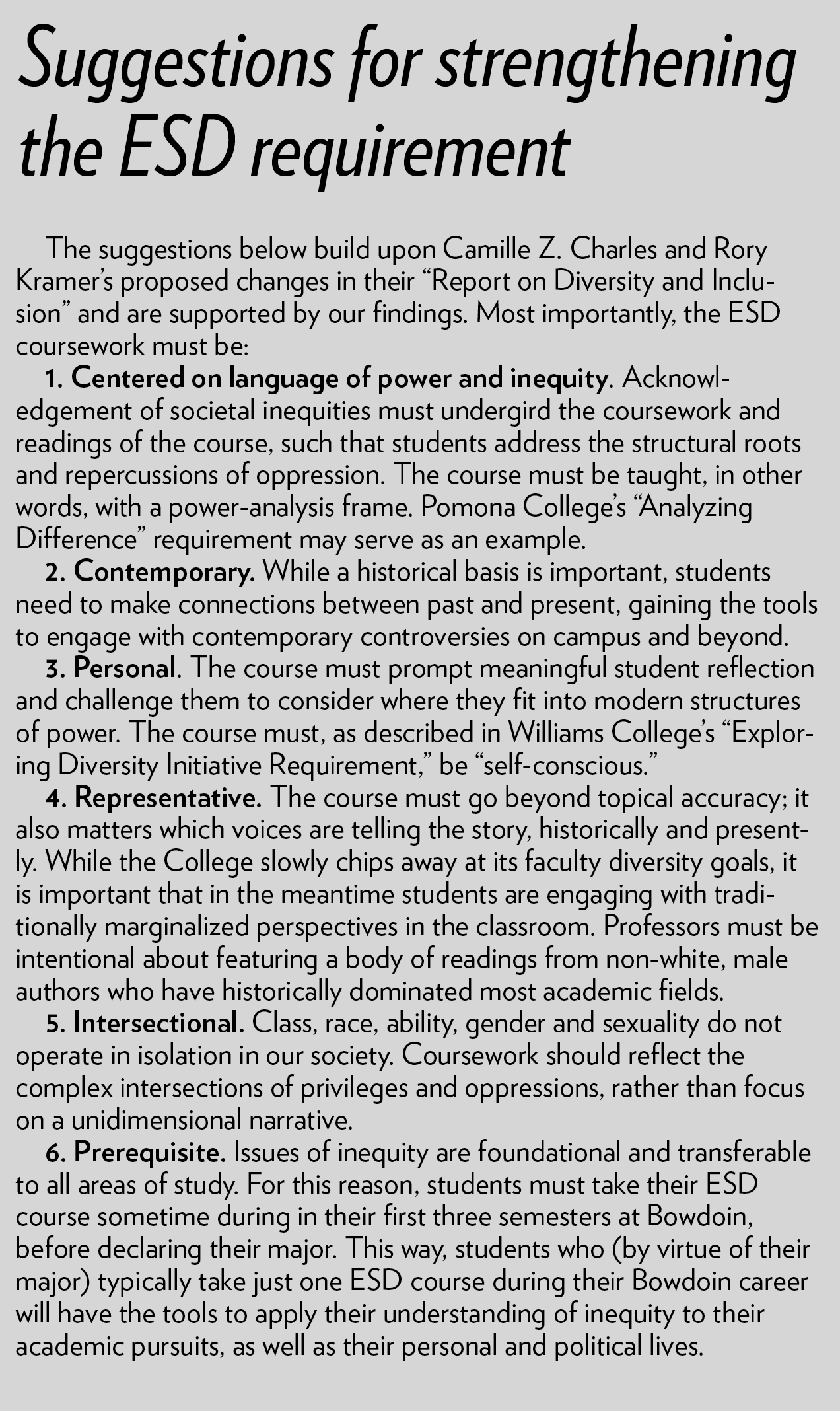

Since most courses at Bowdoin do not explicitly tackle inequity, the ESD distribution requirement shoulders a heavy task and fails. In the next few years, the Curriculum Implementation Committee and the Curriculum and Educational Policy Committee will reevaluate the ESD and IP distribution requirements and potential changes. We see this as an opportunity to rethink how Bowdoin educates students about inequity—racial and otherwise. Changes to the curriculum could take on various shapes. For example, students could all take the same foundational ESD course providing them with a shared structural understanding of race (not to mention class, gender, etc.) that helps their racial discussions be more productive. ESD courses could also be tailored within specific majors, so that students in all disciplines would be familiar with how race affects their specific area of focus.

We believe it is the duty of faculty committees to parse out the specific implementation of this new requirement and the institution’s responsibility to implement these changes, as it is essential that students graduate with a robust understanding of inequity.

These proposed changes to the ESD requirement were presented to the Curriculum Implementation Committee and the Curriculum and Educational Policy Committee in late February. They were received well and we hope to see the committee include the campus in further discussion about future changes as their work progresses. By expanding effective education on inequity for the entire student body, Bowdoin strengthens its long-term commitment to social justice and its core value of the Common Good. It helps students develop habits of critical thinking and encourages involvement in issues of inequity which influences individuals’ political and social practices for the rest of their lives.

Next week, we will turn to an analysis of the racially-charged controversies that consumed campus between fall 2014 and spring 2016. Our work will address the differences in response among students and by the College, as well as the variation in the way students remember these moments.

This article also draws from analyses by Julia Conley ’18 and Diana Furukawa ’18.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Amazing how “Curricular reform” equates to identity politics in the author’s mind. The reason the majority of students want no part of your “racial education” is that they think it is BS. Your claims of marginalization, structural inequality, “power” and the “burden” you face “educating” the rest of us has become tiresome. We simply want to interact with you as fellow human beings. If you insist on every interaction being viewed through the lens of identity politics, you will continue to shout at the same room full of 20 radical, unhappy students. The rest of us will enjoy interacting with each other as equals.