Seeing structural oppression in shades of grey

March 30, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Morality has a number of purposes. There’s a social purpose; it makes people’s behavior predictable and helps us to resolve conflicts peacefully. There’s also a critical purpose, which is often at odds with the social purpose; morality provides the basis for us to criticize society, government, culture and even morality itself. Finally, there’s a weighing purpose; in situations in which our attention, energy and resources are limited or divided, morality helps us to see where they should go. If we are unwilling or unable to draw moral distinctions, we lose this ability to weigh—in fact, to see.

Structural oppression is an increasingly common topic in political discourse, especially on college campuses. This is obviously a good thing. Oppression will continue as long as oppressive structures remain intact. In order to dismantle these structures, we should understand how our actions (and inaction) reproduce them. Along these lines, I should emphasize that what I say here shouldn’t be taken as criticism of our focus on structural oppression but rather as a word of caution about how it is discussed.

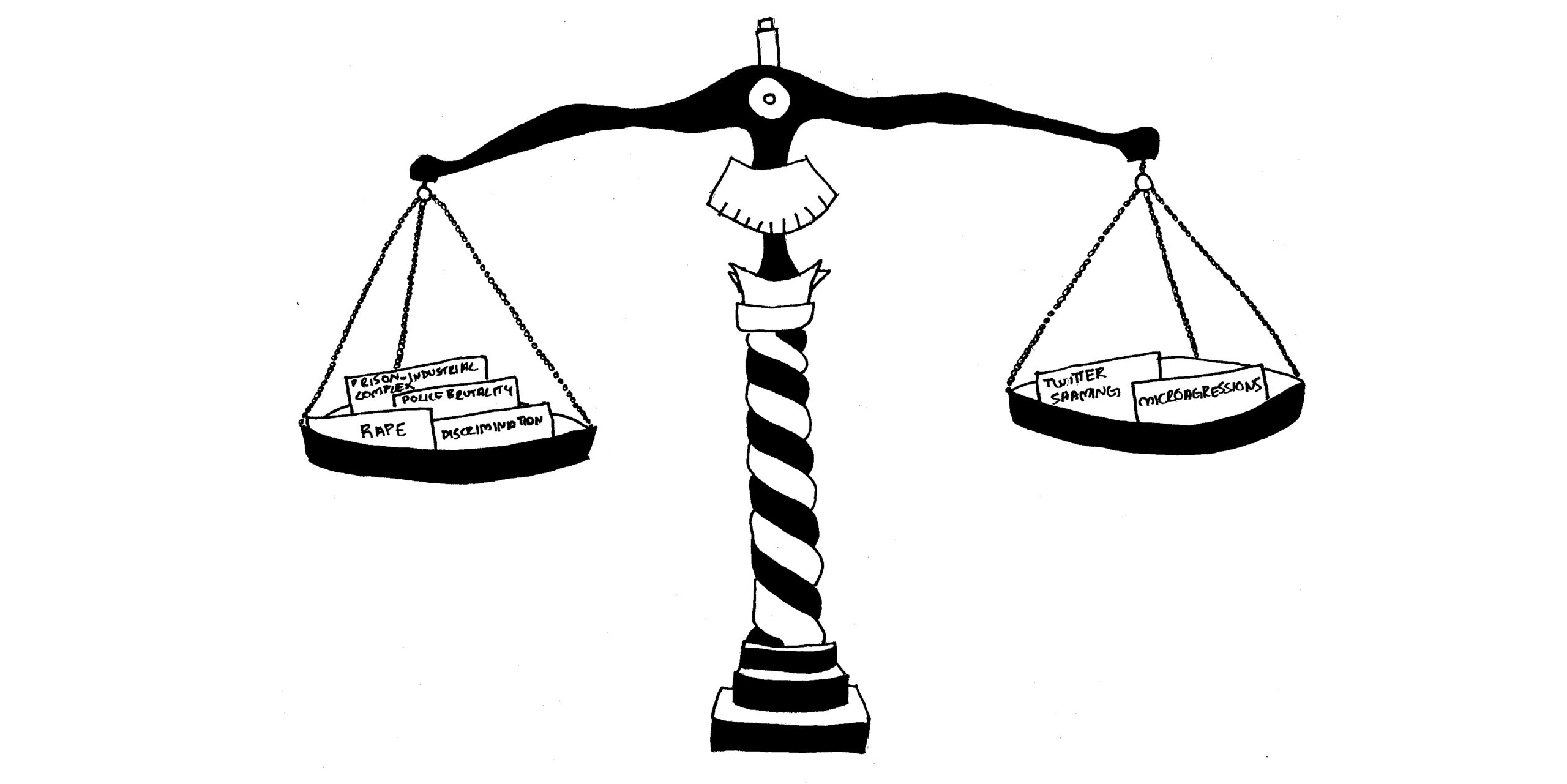

I fear that our discussions of structural oppression are dangerously over-simplified, morally speaking. We seem to treat any action, utterance or cultural artifact that reflects or perpetuates structural oppression as just as bad as all the others—as if everything that perpetuates oppressive structures does so equally and as if all the effects of these structures are equally bad and therefore equally deserving of our energy and attention. We seem, in other words, to have lost our ability to weigh.

“It’s all part of the same oppressive system” is a common phrase at Bowdoin. It is intended, I take it, to mean one of two things. It might be meant to link what I’ll call “the problematic” to what I’ll call “the violent.” The former includes offensive language, TV shows, paintings, and other cultural artifacts, and so forth. The latter includes police brutality, rape, the prison-industrial complex, employment and housing discrimination, etc. Insofar as both the problematic and the oppressive reflect and perpetuate the oppressive structure as a whole, to link the two is not incorrect.

But people who say the phrase above might mean it in a stronger sense. Instead of merely linking the problematic to the violent, they might instead mean to equate the problematic to the violent. If equating is what people mean to do—if, in other words, they mean to say that all issues that reflect or perpetuate structural oppression deserve our attention equally, that we can’t possibly address the violent without addressing the problematic, or that the Dana Schutzs and the Al Frankens of the world are just as bad as the George Zimmermans and the Harvey Weinsteins—then the claim is wrongheaded and counterproductive. To reply that saying something like this constitutes a defense of the problematic (of the Al Frankens for example) would be to miss, if not prove, the underlying point. Because to conflate distinguishing the problematic from the violent with defending the problematic would evidence a failure to see these issues in shades of grey, which is just what I am arguing that we need to do.

Of course I don’t believe that anyone actually thinks all issues that can be traced back to structural oppression are the same—very few people actually mean to equate the non equivalent. But many people seem to see no point in acknowledging the differences between the problematic and the violent or even seem to think that doing so contributes to structural oppression. Accordingly, the problematic instances of structural oppression get just as much airtime, just as much energy and attention, as the violent do.

This has real consequences. When everything is judged solely based on whether it reflects or perpetuates oppressive structures, and not by any other criteria whatsoever, small changes in our behavior and speech become just as important as real action to dismantle oppressive structures—action, that requires us to look beyond Bowdoin. Along these lines, I see this unwillingness to weigh as the root cause of what many have called “performative woke-ness.” Twitter-shaming celebrities and using only the most up-to-date, ostensibly oppression-free language has become just as important as fighting the repeal of DACA, demanding policing and sentencing reforms, supporting the people who are suffering the worst harms of climate change, pressuring U.S. leaders to do more to prevent genocide in Myanmar, etc. (On that note, I think something is wrong when the term “micro-aggression” is used far more frequently at Bowdoin than the word “Rohingya.”)

I say this all somewhat reticently, because I recognize that many of the debates that occur at Bowdoin and on other college campuses are about creating an environment that is safe for and welcoming to marginalized students. That is a worthy goal, it should not get as much resistance as it does. And I certainly do not intend this piece to contribute to any effort to undermine it. But it can’t be our only goal, and sometimes it feels like it is. Despite what many would have us think, Bowdoin is part of the real world—structural oppression plays out here, as it does everywhere. But changing Bowdoin will not change the world. To see this requires us to see structural oppression in shades of grey. Otherwise, we cannot see it at all.

Atticus Carnell is a member of the Class of 2018.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: