The border wall and its impact on the environment

January 26, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Over Winter Break I spent a week in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas, along the Mexican border. I was there on a birding trip because, ecologically, the area is an extension of Mexican habitat—much of its native wildlife can be found nowhere else in the U.S. Although the valley is largely developed, several parks and refuges protect patches of pristine, unique habitat along the Rio Grande River—thick, subtropical riparian forest and mesquite scrub bursting with colorful tropical birds and butterflies. The valley has distinct cultural characteristics, as well: most signs are in Spanish, and the contributions of Latino immigrants who make up the vast majority of the population (90-97 percent depending on the county) are obvious.

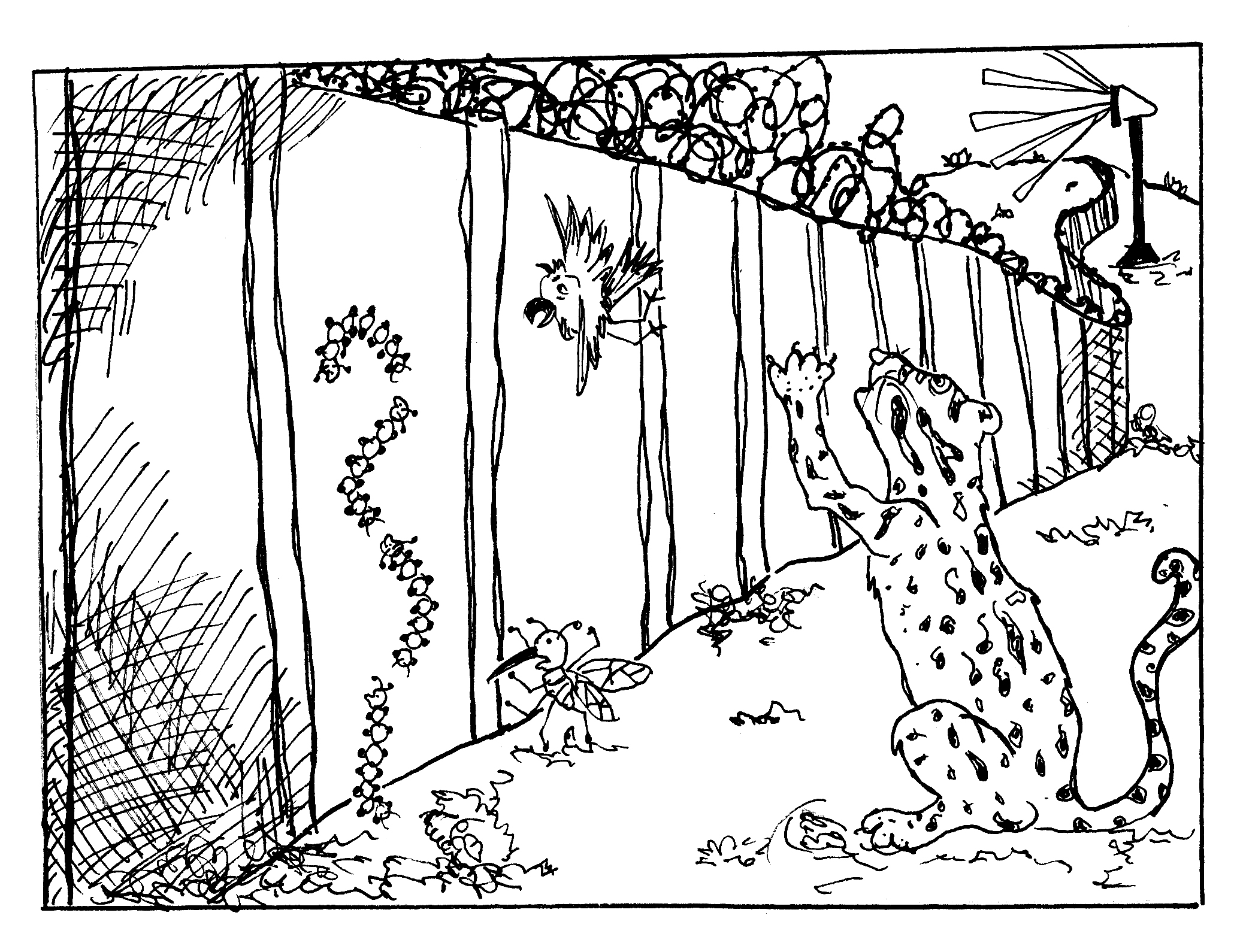

Today, of course, a shadow hangs over the region. The valley is currently ground zero in the fight against the border wall. If President Trump’s administration has its way, the first segment of wall will be built in the heart of the region’s largest and most famous preserve, Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. Standing atop the observation deck at the refuge, which rises above a thick canopy, I was able to look south across miles of unbroken forest, unsure of where exactly the border (the river) lay. The wall would change that—for maintenance and security purposes, huge swaths of the forest would be cleared and replaced with patrollable roads, flood lights and the barrier itself. As I took in the scenery, listening to the calls of green jay and great kiskadee, I became painfully aware of the situation’s gravity. A border wall promises more than just humanitarian conflict. It spells out environmental ruin as well.

The environmental consequences of the border wall have so far been mostly glossed over, and understandably so—the wall is first and foremost a barrier against human migration, and we mustn’t forget the horrendous impact its construction would have on already-marginalized communities. Yet, in many ways, the wall is just a physical manifestation of a conflict that has been ripping local communities apart for years.

It is this manifestation of the conflict that now threatens the local environment. The Rio Grande Valley is, by all natural criteria, a continuation of Mexico. It’s actually a floodplain, extending outward on either side of the river. Wildlife doesn’t recognize political borders, and so there’s a large amount of movement across the river (which is rather narrow at points) and up and down its banks. Close to 30 species of bird found in the valley exist nowhere else in the U.S., even though they have extensive ranges south of the border. Over half of all the butterfly species in North America live in the valley, and many are of similar Mexican origin. Numerous species of mammal, including iconic tropical species like ocelot and jaguarundi, navigate the corridor on either side of the river. Isolated tracts of protected land across the valley aren’t enough to preserve this level of biodiversity– wildlife corridors are crucial to the health of such an ecosystem. Fragmented parcels of habitat will lose biodiversity quickly if free movement between habitats isn’t preserved, and in a natural riparian corridor such as the valley, this movement is an integral part of the region’s ecology.

At a minimum, the border wall’s creation would destroy unique habitat. But its detrimental effects would continue after construction: it would act as a barrier to wildlife movement with even more potency than it would deter human migration. With its route winding a few miles inland of the river itself, more northerly preserves would be actively cut off from reserves right along the border. This barrier wouldn’t really impact the dispersal of birds, but the necessary movement of mammals, herpetofauna and certain insects would be strangled. For some of the larger mammals especially, the border wall could spell their extinction north of the border. Furthermore, wall security, maintained by heavily patrolled roads and intense floodlighting, would disrupt nocturnal wildlife activity—the lighting especially could disorient and impede the movement of migratory birds that funnel through the region in spring and fall.

It’s also worth noting that, in the valley especially, a healthy environment supports the local community in measurable economic terms. Ecotourism brings large amounts of money to the area. In seeking out the unique wildlife of the valley, I spent money at local restaurants and camping grounds, most of which are owned and operated by Latino immigrants regularly demonized in our nation’s capital. Ecotourism in the region could take a serious hit after the wall’s construction, for some of the most pristine wildlife viewing areas in the valley are right along the banks of the river, and these areas would effectively be cut off from the community and tourists hoping to visit them. Racial politics are at work here—the local economic pain that will be felt after construction is one reason why the wall faces intense local opposition. We must wonder: if the valley was a predominantly white community, would the wall still be built there?

Bringing up the environmental consequences of a potential border wall need not draw the spotlight away from humanitarian issues. The two are intertwined and both important: we have a responsibility to preserve this country’s unique habitats and the wonderful wildlife that inhabit them.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: