Reclaiming ‘#MeToo’ as a Woman of Color

November 17, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

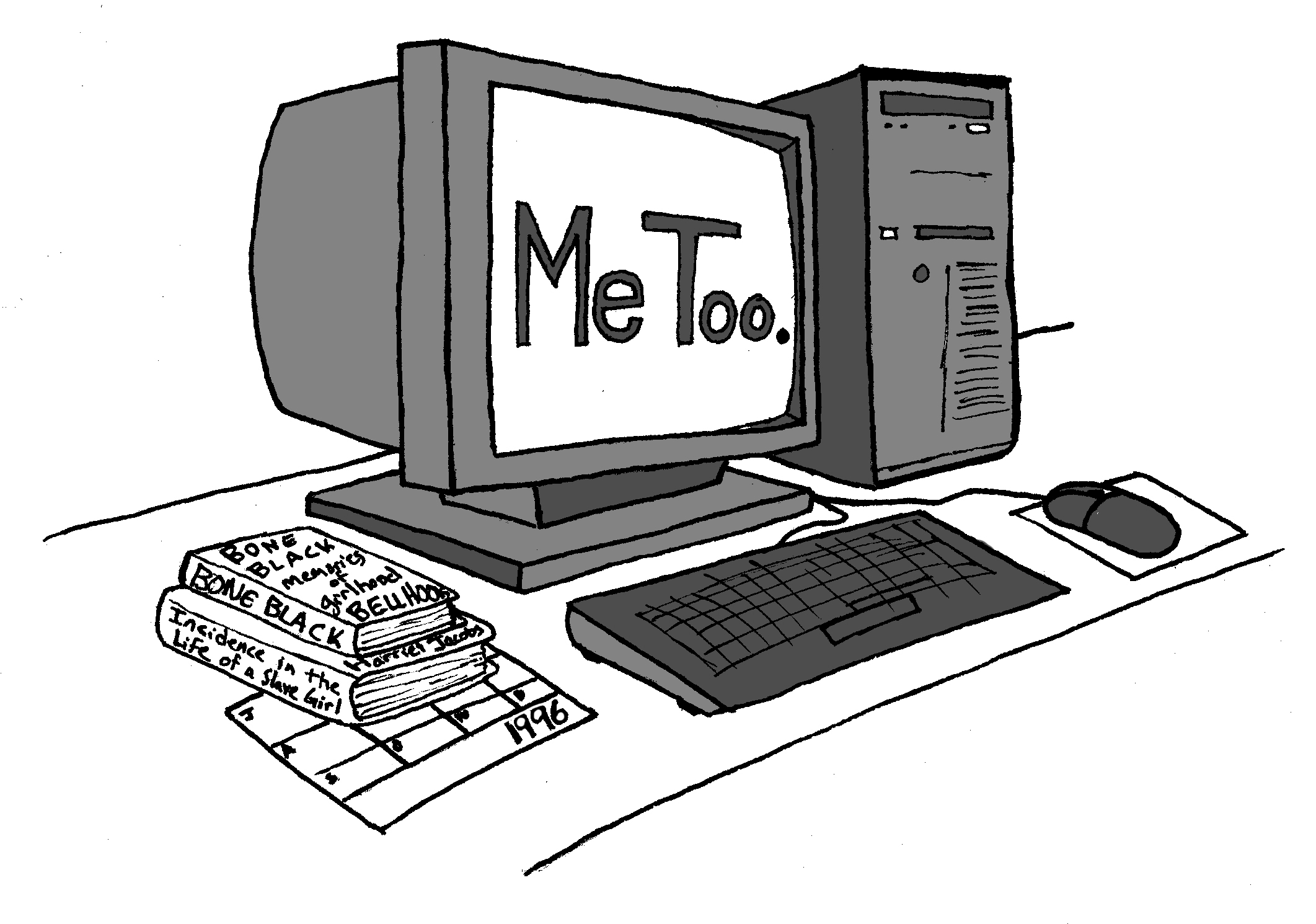

A few weeks ago, while scrolling through “The Shade Room,” a news platform on Instagram, I came across allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, specifically his various acts of sexual harassment and assault towards his female colleagues. Days later, the words “Me Too,” preceded by the hashtag symbol, began circulating throughout my Facebook newsfeed. One of the survivors, Alyssa Milano, tweeted “#MeToo” as a way to call on victims to share their experiences. Therefore, this hashtag was used to further the efforts of many women that came forward to share their harassment and/or assault by the producer. Many women—and some men—around the world have tweeted “#MeToo” as a means to “give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”

Due to the fact that we currently live in a social-media driven society, viral responses often speak to the necessity of addressing a particular issue. For example, the rates of sexual assault on college campuses, and beyond, are alarming; thus, it is of paramount importance to raise awareness on the matter. “#MeToo” provides the space to actively share countless experiences of sexual harassment and assault, and to highlight the unfortunate reality that these situations are not rare. “#MeToo” allowed survivors around the world to build a virtual community centered on sincerity, empowerment and support.

As a Black woman, I hesitated to participate in the viral response as I struggled to see where the narratives of women of color (WOC) fit into it. On one hand, tweeting “#MeToo” broke the cycle of silence and voiced the prevalence of sexual assault within communities at large. On the other hand, it failed to provide an accurate representation of the hashtag’s roots. As I saw these sudden waves of acknowledgement of sexual assault, I could not help but reflect on its origins. While “MeToo” resurfaced as a hashtag with Harvey Weinstein, it began as a movement in 1996 by Black activist Tarana Burke. Burke was aware of the rape and assault inflicted on Black women since slavery, and knew that WOC did not have the appropriate space to address these issues. This silence perpetuated a system of dissemblance and undermined the magnitude of sexual assaults within communities of color; this consequently reduced the resources available for survivors in these communities. For these reasons, “MeToo” was started to dismantle the narrative of misrepresentation and erasure of the experiences of WOC, and to offer a platform of support and resources for survivors from these silenced communities.

While I recognize the positive effects that “#MeToo” have had for some women, I struggle to comprehend how this viral response serves to dismantle the power structure that allows for sexual assault cases to be so rampant. In order to solidify the aim of “MeToo” as a hashtag, I believe there is something valuable about incorporating its founding principles and redirecting it to its roots. The Alliance for Sexual Assault in Connecticut released that “American Indians are raped at a rate 3.5 times higher than any other race,” and that for “every African-American that reports her rape, at least 15 African American women do not report theirs.” The disproportionate rates of sexual assault among communities of color make it necessary for us to discuss these differences, and to use “MeToo” not only as a hashtag, but also as a movement. I believe this will provide equitable support and resources for survivors of all races and ethnicities.

Anu Asaolu is a member of the Class of 2019.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: